By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

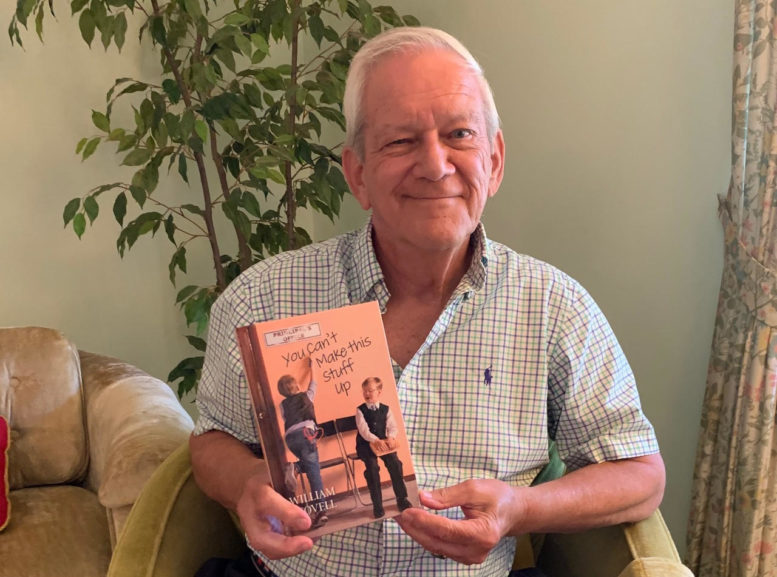

William “Bill” Scovell rubbed elbows with Nobel laureates. He wrote three academic books and over 60 scientific journal articles.

The now-retired Bowling Green State University professor was considered one of the internationally recognized scholars in biochemistry/molecular biology as it relates to a role of a cellular protein that enables estrogen responsiveness.

Those chapters of his life–over 50 years that included academic rigor, intensive research and more than 20 National Institutes of Health grants—are bookended by a different genre.

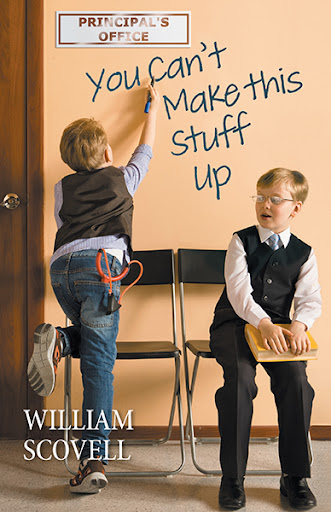

His most recent writing feat is a 222-page collection of 20 short stories that combine nostalgia, humor and a positive outlook on life lessons.

Scovell said his book, “You Can’t Make This Stuff Up,” is autobiographical fiction. Many of the short stories are based on his life, from growing up during the air-raid era in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, to conference-attending adventures in Czechoslovakia in the late 1980s.

His beginnings were humble and unassuming. Throughout elementary and junior high schools, he wasn’t a very good student. “I didn’t take school very seriously until about the 10th grade,” Scovell admitted. “I didn’t like general science. Biology and chemistry were easy and physics was OK. I thought I might be a chemist because it’s about equations and descriptions.”

That is what set him on the path to study the sciences.

His father, who owned a paint store and painting business where Scovell gained his strong work ethic, wasn’t sure about a career in chemistry for his son, especially not in research.

“In my generation, our parents felt that the boys had to go to college, but they didn’t care what we studied. I thought I might be a pharmacist or chemical engineer, but once I found out what a chemical engineer does, I wasn’t interested in that,” Scovell said.

A couple of university chemistry professors took an interest in him, and encouraged him to consider graduate school to pursue a teaching and research career.

He earned his doctorate in chemistry from the University of Minnesota where he and his wife, Eleanor, lived for four years. She worked as a surgical nurse at the University Hospital with Dr. C. Walton Lillihei, who is regarded as the father of open-heart surgery, and he became absorbed in the field of chemistry.

A combination of serendipity and perseverance on his part over several years forged a new direction for the chemist turned biochemist turned molecular biologist.

A post doctorate opportunity at Princeton introduced him to the “excitement of biology.”

He joined the BGSU faculty in 1974 as the first researcher on campus to use a laser in his research.

Scovell learned from scientists who were making great strides in cancer chemotherapy with a platinum-based component. He became interested in biological techniques, DNA, genes and gene expression, and developed his own theories about platinum interacting with DNA within the cell. Eventually he presented his research ideas to the National Institutes of Health and earned the first of many NIH grants.

For 30 of the 35 years he was at BGSU, he had NIH grants. He wrote more than 20 grant proposals during his career and became known as an expert in his field of research. He retired in 2010, but stayed one more year to wrap up his final NIH grant.

The transition from academic science writer to creative writer was prompted after a college class reunion. A group of college classmates “wanted to get to know one another better, so we wrote a five or six page paper about what we’d done since we graduated,” Scovell recalled.

That assignment made him think that his four children—Sherry, Bill Jr., Jeffrey and Christopher—didn’t know much about him other than his work. He wrote a 220-page memoir about grade school, high school and college, and shared it with them. The three doctors and one businessman encouraged him to turn his memories into a book.

Scovell found this new-found writing process to be refreshing.

“In science you propose you are going to look at something and determine something about a scientific area. You write a hypothesis, with specific aims and what you are going to do. You write a paper that is peer reviewed. Scientific research and its writing can be especially constraining because you need data and you need to interpret it,” he said.

“On the other hand, with this kind of book, you’ve got no constraints. It’s picking the right words, interesting words and interesting sentences, but you can go anywhere with it. It’s so much fun.”

His favorite stories include the ones about Little League Baseball and the air raid practices in grade school. But he admitted that he still chuckles when he reads the other stories like “I Spent a Lifetime in a Calf Slaughterhouse One Afternoon,” and “Dusty’s Picture of Mickey’s (Mantle) Big Year.”

While he has written about a dozen more stories, it’s uncertain if they will be published.

The entire process of writing, editing, and publishing is a time-consuming process. He is not discounting it. If “You Can’t Make This Stuff Up” is well received, it’s a possibility.

The book is available online at the Friesen Press website, Amazon , Barnes & Noble , and Apple Books .