By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Picture this. Three black teens place their order at a sit-down restaurant, and are told by the waitress that they will have to pay for their food first. Or a transgender woman is scolded by another customer for using the women’s restroom. Or a biracial couple is met with criticism for their decision to date.

What would you do as a bystander? Would you freeze, then be angry at yourself later for not intervening? Or would you do something?

Sometimes a dirty look is all it takes. Other times, a request to talk with someone in charge. Or sometimes it may take a phone call to the police.

Earlier this year, some citizens of Bowling Green were horrified after two brown teenagers were called racist names and assaulted by two white men at the local Waffle House.

The community mobilized. Meetings were organized by LaConexion, and the police division created training for businesses on how to handle such incidents. But citizens still wondered how they could be more than silent bystanders when discrimination occurs.

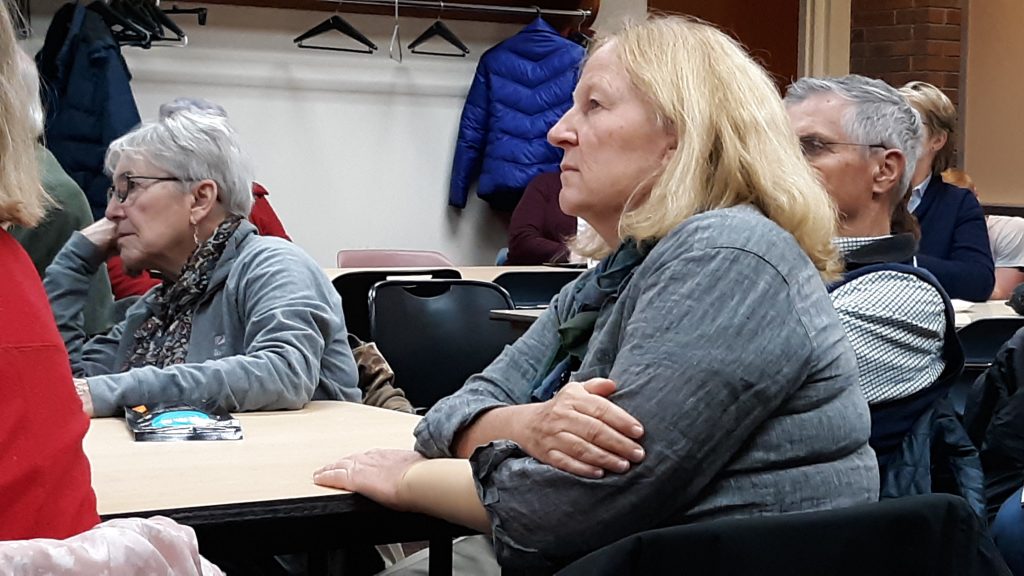

On Wednesday evening, more than 50 citizens gathered in the library for bystander training organized by LaConexion’s Immigration Solidarity Committee.

“What can we do as businesses to try to stop these incidents before they happen?” asked committee member Linda Lander. “What can we do as citizens to stop this behavior?”

Bowling Green Police Detective Scott Frank reminded residents that the city already has an anti-discrimination ordinance in place. Businesses are not allowed to let discrimination occur. They are allowed to kick out people whose behavior is not permitted. And if the business fails to take action, then citizens can file complaints with the city administration, Police Deputy Chief Justin White said.

“Be the best witness you can be,” White said.

Ohio has no legislation increasing penalties for hate crimes. But Bowling Green has an “ethnic intimidation” provision that can result in the offense being more serious, Frank said.

“Ethnic intimidation” can be anything that denies equal services to someone based on their race, religion, gender or sexual orientation.

When citizens come across ethnic intimidation occurring, Frank suggested there are varying steps that can be taken. It may be awkward – but so is standing by and doing nothing.

“Do something,” he said. “Doing nothing is turning a blind eye and letting it continue.”

That may mean just giving a “dirty look,” or asking in a polite manner that the behavior stops. If the behavior continues, talk to the management or call the police.

“Do not hesitate to call the police,” Frank said. “I would rather we deal with it, and quash it before” it becomes a full-blown physical altercation.

Businesses wanting to get rid of patrons who are discriminating against others, can ask them to leave. “That’s your house,” Frank said.

And if they don’t leave, employees should call the police.

Sometimes it’s not outright hostilities, but microaggressions, micro-insults or micro-assaults that demean, denigrate or threaten people, explained Ana Brown, director of the Office of Multicultural Affairs.

Those can include statements like, “You don’t act gay,” or “You’re pretty for a black girl.” These acts can include use of a confederate flag, a “Chief Wahoo” hat, or Nazi swastika.

Many people don’t intend to be hurtful or insensitive – but they are, Brown said.

“It’s really, really important to understand the other perspective,” she said. “Good intent does not make bad impact OK.”

“We all have biases. It’s a matter of how we act on them or don’t act on them,” Brown said.

Members of the audience shared their own experiences of micro-behaviors based on biases.

Kathy Pereira de Almeida spoke of the time when she was shopping with her mother-in-law, and speaking in her mother-in-law’s native language.

“I’ve been asked to speak American,” she said.

Another woman recalled when she started a new job in a male-oriented workplace. A male co-worker scolded her for taking the job away from a man who needed to support a family.

And Melanie Stretchbery talked about members of the community who referred to themselves as “colorblind” after the Waffle House incident. That just isn’t so, she said.

“We need to find a way in our community to respect our diversity,” Stretchbery said.

Two speakers from the BGSU Center for Women and Gender Equity – Faith DeNardo and Jamie Wlosowicz – talked about different levels of bystander intervention. They also cautioned about the “bystander effect,” which is the phenomenon that if more bystanders are present, more people believe someone else will intervene.

Intervening can take different forms, such as:

- Direct, in which you confront the person or the situation.

- Distract, in which you defuse or disrupt the situation by taking such actions as yelling, honking a horn, or spilling food or a beverage.

- Delegate, in which you request backup from someone else, such as a friend, management, or police.

Videotaped scenarios were shown, such as the case of black teenagers being asked to pay before getting their food. Participants were asked how they might intervene if they were dining at the same restaurant and overheard the waitress telling them they had to pay first.

Local citizens said they would ask the teens if they would mind some help, they might pay for the meals themselves then ask to talk to the management. They could ask to see the restaurant policy, and contact the corporate office.

Concerns were also expressed at the meeting about people reacting with fear or suspicion to people of color doing typical behaviors. National news has reported on police being called for black people walking in neighborhoods or sitting at coffee shops.

“Please, make sure what they are doing is actually a crime before you call the police,” Brown said, noting that some BGSU students feel unwelcome in the community because townspeople react with suspicion to them.

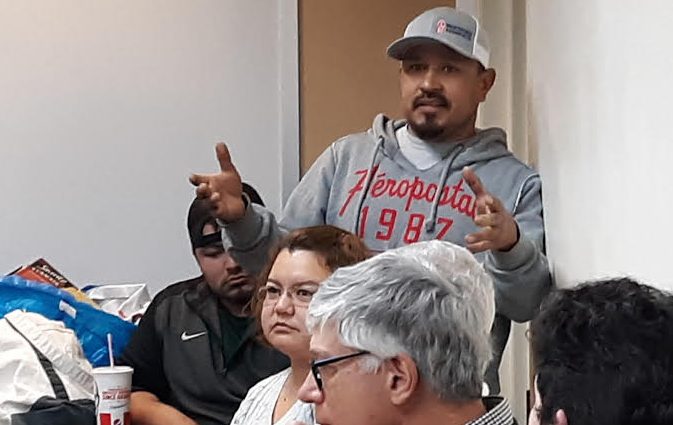

A Hispanic man talked about a young boy in his neighborhood who was playing with other children. A neighbor called police because the boy was playing with a piece of wood that looked like a gun. The police responded with guns drawn, he said.

“He almost died because he was a colored kid,” the man said.

If police are the problem, and citizens believe they are being overly aggressive with minority suspects, then citizens should not attempt to intervene then, but should report their concerns, White said.