By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

The textbook in Heidi Meyer’s high school social studies class at Elmwood has one paragraph about the Holocaust. That doesn’t stop her from expanding the history lessons into a monthlong unit that includes field trips, guest speakers and lots of discussion.

In the rural school that has just over 300 students and very little diversity, Meyer wants to make sure her students are taught about the Holocaust “so they don’t repeat it,” she said in her classroom on Wednesday. “I want them to understand humans are humans, and we should love everybody.”

Her lessons are not part of any trend in cultural training, but instead a reflection of who she is. She grew up visiting historical sites for vacations with her Curtice, Ohio, education-focused farm family. A college course about the Holocaust “took me down a road that I just kept going down. It became my passion project,” she said. “I was so amazed by it and how people could do that to somebody else.”

For 18 of her 23 years of teaching—16 of those at Elmwood—she has incorporated the Holocaust into her lessons by visiting a Holocaust memorial or museum. More recently, she has connected with the Jewish Federation of Greater Toledo to explore additional ways to bring the lessons to life.

In March 2023, after noticing the school was “experiencing a lot of racism and cultural insensitivity,” she wrote to the federation asking for any kind of assistance. “We want to combat it with knowledge. We want to bring in speakers that would help connect the dots for the students,” she said.

And they responded. The federation has provided speakers in the classroom and trips to local synagogues. Students have learned about the Holocaust and Judaism from local community leaders, Holocaust survivors and their offspring.

Meyer’s “unwavering commitment to combating ignorance with knowledge and fostering empathy” earned her the Shine a Light on Antisemitism Civic Courage Award, a national award presented by The Jewish Education Project. She is one of two high school educators from across the nation and one of two Ohioans to receive the prestigious award for 2024.

Stephen Rothschild, CEO of the Jewish Foundation of Greater Toledo, called Meyer “an upstander, not a bystander.” He said the Holocaust happened because there were way too many bystanders. “There were people who were apathetic about what was going on with their neighbors.”

The Germans didn’t wake up one day and decide to exterminate all Jews, he continued. It was a well-thought-out campaign of propaganda to completely ‘other’ the Jewish people and allow people in power to take advantage of the situation.

“Heidi doesn’t accept that,” Rothschild said. “In the words of Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, ’Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.’ You can’t be silent in the face of injustice is an important message, and it’s one that Heidi has internalized and lived by.”

‘Whoever listens to a witness, becomes a witness’

“There’s so much distortion and denial of the Holocaust,” Meyer said. “People don’t know what the Holocaust is because it’s not taught.” Additionally, a statistic from an Anti-Defamation League survey that was released this week indicated that 46% of people around the world hold some deeply anti-Semitic views.

Those concerns make her sad but also drive her to go full throttle to fight injustices against others. She teaches kindness in everything she does, but her big teaching moment comes every spring when she plans her Holocaust unit for February into March.

Meyer’s first foray into teaching about the Holocaust started when she was working for Put-in-Bay schools. Because field trips with 10 students were fairly easy to do, she took them to the Zekelman Holocaust Center in Farmington Hills, Michigan, a memorial she had not previously been aware of.

Since that inaugural trip to the Michigan memorial, she has taken students, first from Put-in-Bay and then Elmwood, to visit and become immersed in the past. Listening and learning about the stories of courage, perseverance, loss and redemption from local Holocaust survivors often provides a lasting impact for her and the students.

More recently with grant support from the Ohio Holocaust and Genocide Memorial and Education Commission, she has broadened the experiences to include some of Ohio’s Holocaust memorials including the Nancy and David Wolf Holocaust and Humanity Center in Cincinnati and this spring’s trip to the Maltz Museum near Cleveland.

Meyer hopes listening to the survivors’ stories and learning about the Holocaust is a wake-up call to the words of Wiesel: “Whoever listens to a witness, becomes a witness.”

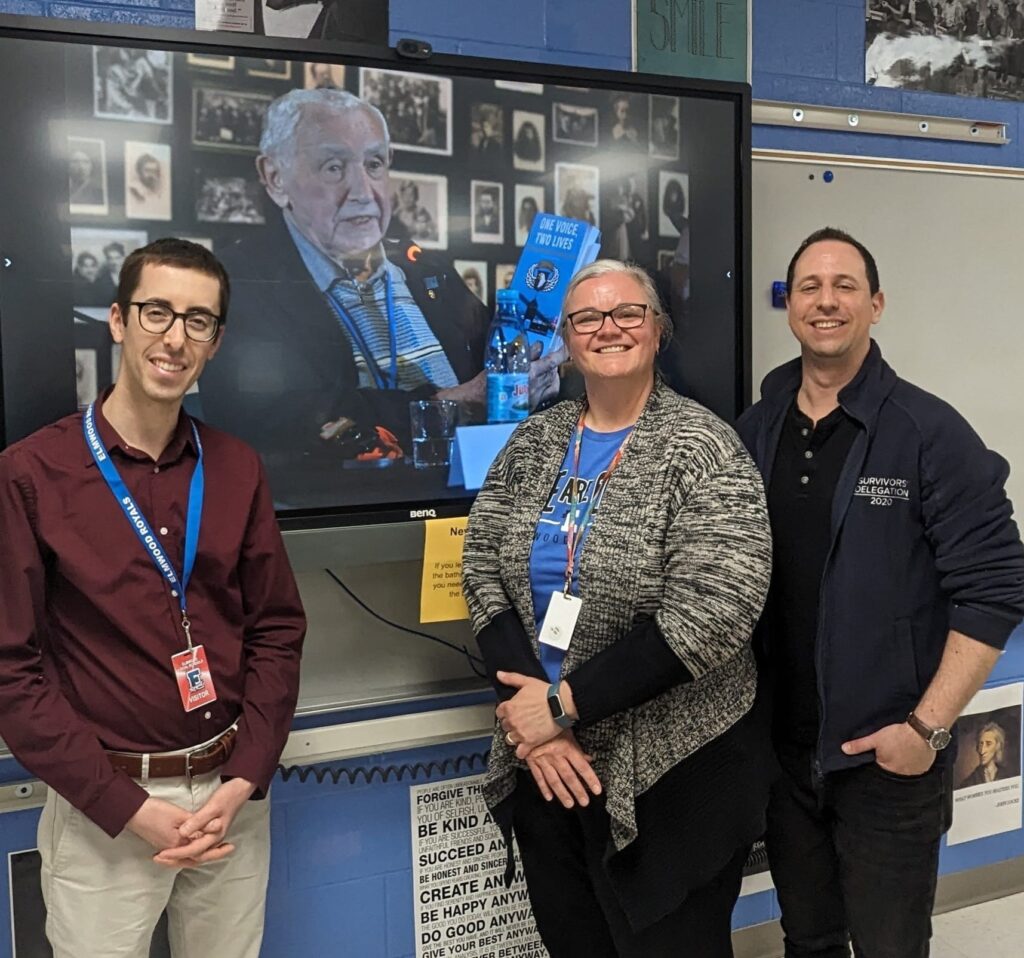

After a classroom visit by Avi Wisnia, director of a documentary about his grandfather’s experiences during the Holocaust, Meyer saw Wiesel’s words play out. Students talked about the experience for days. Meyer heard the buzz in the hallways and realized the ripple effect worked. Her students were sharing what they learned with other students and their families.

Combatting antisemitism and more

When the Holocaust unit begins, she lets them know any nasty comments and jokes are not allowed. “If you say these things, I will immediately kick you out. You’ll have a detention, and I will call home, because this is serious,” she tells them.

Once the ground rules are set, she starts the unit talking about what life was like for the Jews before Hitler came to reign. “They were living their lives, and you would never know they were Jewish. They are just like us,” she said.

Before Hitler labeled the Jews as bad, they were riding bikes, hanging out with their friends, sledding and doing things that everyone does. “I want to make it personal for the students so they make connections.”

They also start to understand by hearing firsthand about the Jewish faith. This year, Amichai Stout, community relations director at the federation, will visit the classroom to talk about what it means to be Jewish and to show them there are many more similarities than there are differences.

“I think it’s really important for my general ed kids to meet someone who is Jewish,” she said. “When you meet somebody, you see they are really nice, and you understand they are not just a label. So you are not going to say silly or nasty things about Jewish people.”

Meyer also introduces students to the Muslim faith to dispel some of the stereotypes often associated with Muslims. The AP students visit a mosque, and speakers visit the class to talk about their faith.

“The students have never been exposed to other people who have different faiths, so let’s go and find out about them to see they are loving and kind,” she said.

An additional immersive experience that she has offered in the summer is a trip to Europe for a World War II tour. “I know not everyone can afford it, but I try to offer up opportunities” to educate students and adults about the Holocaust, she said. “Education is super important to me.”

While combatting antisemitism is foundational, Meyer’s passion for teaching about the Holocaust goes beyond a mere history lesson.

“In my classroom, I’m all about kindness,” she said, teaching and modeling that from Day One. ”If you come at me in a kind manner, I will respond in a kind manner.”

She also knows her job is not to tell students what to think but to make them think for themselves.

“I teach political discourse in here because my hope is that they will take that to their families and out into the community,” she said. “That is what we’re missing in our world. I’m trying to be the light, to teach them how to love each other and talk to each other.”

She doesn’t always know she has made an impact, but she hopes she has at least planted a seed.

Beyond the award

Meyer, who is humbled by the award, is quick to take the spotlight from herself and instead focus on others. One of the most important outcomes for the award is giving her a platform to encourage other educators to get involved in teaching about the Holocaust.

She urges others to make use of the myriad resources that are available in Ohio. There are Holocaust grants that will pay for field trips, speakers and professional development, she said.

“I want teachers to know that this resource is out there. It’s easy to write. They approve it immediately, as long as it makes sense,” she said. “They want to use the money for education for the Holocaust, and if you need help, they’re always willing to help. There is no reason not to do this with your Engllish or history class.”

She has only recently added AP classes. “Because the classes are small, I am getting tons of grants to go to historic sites such as Fort Mags, Put-in-Bay, and the Hayes Museum,” she said. She has received grants to take her AP class to the State House and the Ohio Supreme Court.

“I know it’s extra time, but it’s worth it to me because I want these students to have the same education that I want my own children to have. That’s important to me.”

The federation is another important local resource, Meyer said. “When you make those connections with them, they will feed you such great resources and do anything to help.”

Rothschild said that the depth of Meyer’s commitment and the quality of the work she has done contributed to her receiving the award. The award is an acknowledgment of her personal commitment, but it is also meaningful for the federation.

“It’s a recognition that this issue of teaching the Holocaust matters in every community, regardless of how large or small it is. The remarkable thing about antisemitism around the world—it exists in places where there aren’t even any Jews,” he said. “We are grateful for the people like Heidi who are willing to stand by us.”