By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Wood County’s homeless population is largely invisible to the public. They aren’t sleeping on park benches. They aren’t panhandling on downtown sidewalks.

So putting a number on the local homeless population is nearly impossible.

The official annual count is performed overnight on a particular day during the winter, as required by the federal Housing and Urban Development department. Efforts are made to find local homeless by targeting places like 24-hour stores and cars in parking lots overnight.

But those numbers don’t tell the true story of the local homeless issue, since many people without homes in Wood County are “couch surfing” with family or friends, occasionally getting vouchers for hotels for a couple nights, or living in campers or cars.

“We mostly have folks who are doubling up with friends and family,” said Erin Hachtel, area director for United Way in Wood County. “It’s really hard to know what the true numbers are.”

People make the homeless count if they are “staying in a place that’s not meant for human habitation,” she said.

But for some assistance, people do not qualify for help if they are staying with friends.

While the exact numbers are unknown, the increase in requests for help is telling local agencies that the number is growing.

“You can see the numbers go up from 2019 to now,” Hachtel said.

The number of individuals and families seeking help with housing increased greatly in the last three years, according to data collected by groups that offer assistance, including the Cocoon, Great Lakes Community Action Partnership, Salvation Army, City of Bowling Green, Wood County Department of Job and Family Services, and Wood County Area Ministries.

The number of people requesting help for the first time jumped from 847 in 2018 to 1,701 last year. The number of total requests went from 1,404 to 2,506 – many of them from families with children.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated problems that already existed for many families. The lack of affordable housing in Wood County, combined with the loss of employment during COVID led some families to lose their housing.

In order to afford a one-bedroom home at fair market rate, a person in Wood County would have to work 65 hours per week making Ohio’s minimum wage.

In 2021, the average monthly rent at apartments in the Toledo area were:

- $535 for an efficiency.

- $613 for a one-bedroom.

- $793 for a two-bedroom.

- $1,077 for a three-bedroom.

- $1,179 for a four-bedroom.

In Wood County, 28% of households are living at or below 200% of the federal poverty line.

“If you have a minimum wage job, there’s no place you could afford a fair market single family home – unless you work 65 hours a week, every week,” Hachtel said.

“Oftentimes we think of poverty as a personal choice,” but that simply isn’t true, Hachtel said.

“There is a lack of affordable housing,” she said. And the homes that have lower rental rates are often older housing stock that is hard to heat and cool – so the utilities costs are higher, she said.

There are currently 10 subsidized housing developments in Wood County, spread out between Bowling Green, North Baltimore, Fostoria, Perrysburg and Rossford, Hachtel said.

“There’s just not enough,” she said.

“At the end of the day, if we don’t have more affordable housing units, it’s going to be difficult,” Hachtel said.

The problem cannot be solved by private charities alone, or with the creation of a shelter, she said.

“We’d rather have long-term solutions, not temporary ones,” Hachtel said. “We want people to have homes every night, not just for three nights.”

“It’s much, much better if we can put people in an apartment or a house,” and to help people in their homes prior to them being evicted. “We want to do everything we can to keep people in their homes.”

Wood County agencies provide food assistance, and groups like Salvation Army, the Cocoon, and local churches help where they can with housing.

“Our church networks do the best they can,” Hachtel said. “I think our local agencies are doing what they can with what they have. It’s a remarkably collaborative group of people working together.”

But more is needed.

“Private charity cannot solve this problem,” she said.

“We really need everyone to join in this conversation and to be involved in making a difference – property owners, people experiencing homelessness, elected officials, agency folks, and the community at large,” Hachtel said.

The Continuum of Care (formerly known as Home Aid) would love to have more input and commitment to action from all aspects of the community, she said.

“Especially landlords and people who have lived through housing insecurity,” Hachtel said, “to help shape how we as a community can make sure everyone has safe, stable, affordable housing.”

Last November, Justin Rex, a BGSU political science professor, spoke to Bowling Green City Council about how the city can help.

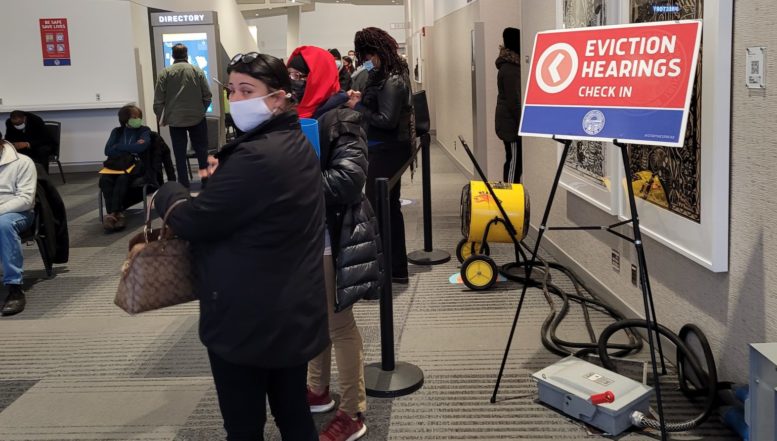

Statistics gathered by BGSU showed that 96% of local residents facing eviction have no access to an attorney. That compares to 10% of landlords. Rex suggested that Bowling Green consider legislation adopted by the cities of Toledo and Cleveland, that gives tenants a right to counsel.

“We tend to think of it as a large city, urban problem,” but evictions happen in all sizes of communities, Rex said.

Another solution the city may want to consider is an eviction diversion program involving landlord-tenant mediation, Rex said.

Rex, who serves on the Continuum of Care in Wood County, said it is difficult to track local eviction statistics. Going back to 2000, there were an average of 313 eviction filings a year – with 138 households actually being evicted.

The numbers grew from 2009 to 2016, when the eviction filings jumped to 538 a year, with 315 actual evictions.

Though a national moratorium was enacted during the COVID pandemic, there were loopholes that allowed landlords to evict tenants, Rex said.

During the moratorium, 163 evictions were filed in Wood County, and 59 in Bowling Green. During that period, 36 households were actually evicted, according to Rex.

“These are formal evictions,” he said. “We know that’s about half of what takes place.”

There are ways some landlords can manage their properties that result in evictions, without the actual legal process, Rex said. For example, some refuse to make vital repairs, raise rents by exorbitant amounts, or even take extreme action like removing an exterior door – in hopes of getting tenants to leave, he said.

Evictions, Rex said, are not always a consequence of poverty. Sometimes, evictions are the cause of job loss and mental stress that then result in poverty conditions, he said.