By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

When U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur arrived at Kris Swartz’s farm in Perrysburg Township Monday morning, Swartz shared a fading photo of the two of them talking on the floor of the Chicago Board of Trade. Swartz reminded the congresswoman that they had just listened to a long spiel about trade changes from a member of the board.

Kaptur huddled together with ag producers from her region and asked, “Is he just giving us a line of crap?” Swartz recalled.

Now, about 35 years later, Kaptur is still looking for straight answers to help farmers and protect waterways of her district from harmful runoff.

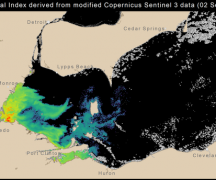

Big picture – she wants to know how to save the Western Lake Erie Basin. But to do that, she needs a collection of snapshots of the region’s veins flowing into Lake Erie, the number of large livestock in the region, and maps of the tiles buried beneath fields.

“I need a complete picture of this puzzle,” Kaptur said Monday as she met with local producers, plus state and federal officials representing the EPA, conservation and agriculture programs.

“I’m just speaking very honestly here,” she said. “After all this money and all these grants that have gone out,” the work is still piecemeal.

“What we need is more comprehensive mapping,” she said, showing a map she drew herself since no agency has come up with a complete map for the region.

“We can’t seem to get the pieces together so we can properly plumb the western basin,” Kaptur said. “I really need your help looking at the pieces of this big basin, so we can make a healthier watershed.”

Kaptur talked about the worries that keep her awake at night.

“There’s no place on earth where this much arable land meets this much fresh water,” she said. “Our job is to preserve it in better shape than when we found it.”

But without data, that’s not possible.

“This is the best ground in the world,” Kaptur said to the farmers from Wood, Fulton, Paulding, Ottawa and Williams counties. “But you can’t find a tile map. If you can – I’ll take you out for a steak dinner.”

Many of the farmers present already practice conservation measures, including Swartz’s family, who has farmed their acreage for five generations. Kris has moved three times in his life – all within a half mile from his homestead.

Swartz showed Kaptur the rye cover crop he planted in his cornfield on Ault Road. He told of his practice of injecting the fertilizer into the ground, rather than letting it sit on top.

Farmers also need more information, he said. They need data on biological diversity, and better information on cover crops. Then there are the extreme climate changes.

“Mother Nature is throwing more water at us,” Swartz said, noting the need for better soil management. “You can do all the good things in the world, and still have a bad crop.”

Kaptur agreed the extreme weather is making it even tougher to protect Lake Erie.

“When it rains, it shoots the water out to the lake like a super highway,” she said.

Debra Shore, regional administrator with the U.S. EPA, talked about the success of Ohio’s voluntary H2O project – but added that more must be done.

“How can we amp up H2O?” Shore said. “This is a problem with no single source, no single entity is responsible.”

Ohio EPA Director Anne Vogel talked about farmers being key partners in finding a solution.

“How do we take this to the next step,” she said of the H2O program. “How do we change the tide?”

Kaptur talked about the new farm bill being discussed in Congress.

“I urge you to give me your best ideas,” she said. “We have an opportunity to do some really great things.”

Ag producers shared their struggles.

Tyler Drewes said ag programs need to consider varying soil types. While certain measures may work for Swartz in northern Wood County, “on my farm in southern Wood County it can be quite the opposite,” Drewes said. “It’s not one size fits all.”

Nathan Eckel, who farms near Swartz, talked about his efforts with manure storage and the voluntary nutrient management plan with H2O.

Kaptur asked the farmers if any of them had been approached about producing power from manure – a common practice in California. Big cattle farms in Indiana are also working on turning manure into power, she said.

Chris Weaver, a farmer from Williams County, has produced power from manure. Though it’s cheaper to put it on crops, it’s “less of a liability and it’s just friendlier” to turn it into power, he said.

Kaptur said the process has great potential. “If we get it right here, maybe they can copy us,” she said.