By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Growing up in Massachusetts, Lynn Whitney had a romantic image of Lake Erie.

In her family home in Concord, Massachusetts, a photograph of her maternal grandfather sailing on Lake Erie in his boat the Sea Saga hung. The lake seemed a place of endless wonders.

But then came 1970, and the burning of the Cuyahoga River. The lake and the region were the focus of attention for the wrong reasons. The lake was dead.

That concern helped spur the creation of Earth Day.

Whitney, who was born in 1953, did visit the state. Her mother’s parents lived in Tiffin, and when Whitney moved to Northwest Ohio in 1987 to join the faculty of the School of Art, her grandmother in senior living center was her “only date.” She was now a photographer with degrees from the Boston University, Massachusetts School of Art and Design and Yale. (Whitney retired from BGSU in January 2021.)

The image of a dead lake was “the image I carried out here,” she said. “That Lake Erie is not a place I wanted to visit so much because I go to Maine in the summer, and what could compare to that?”

Her aunt, who lived in Perrysburg, was active in the Nature Conservancy and was instrumental in the creation of the Kitty Todd Preserve, which bears her name.

Whitney was aware of the revival of Lake Erie as well as the emerging threats to the lake’s health, epitomized by the harmful algae blooms that choked its waters every summer.

In 2009, Whitney received a grant from the Cleveland-based George Gund Foundation to photographically document Lake Erie.

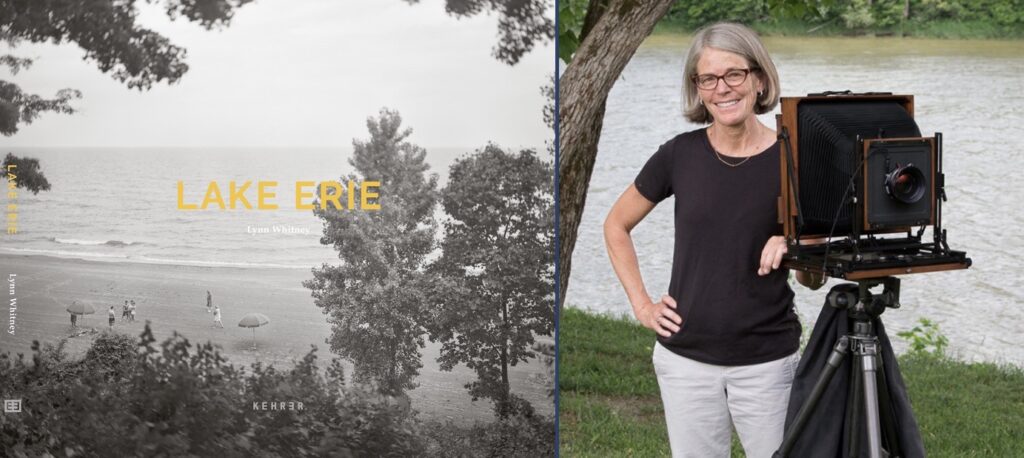

Those photos as well as more recent related work is now available as a book, “Lake Erie” published by the German art house Kehrer Verlag. The book is already available in Europe and will be released this fall. Those wanting a copy can purchase a signed book from her website, lynnwhitneyphotographs.com.

Books will also be available at a reception and book signing marking the closing of the exhibit “Ohio Boundary: Lake Erie” at Lakeside Chautauqua, East Harbor Road, Lakeside Marblehead, on Friday June 30, 3-7 p.m.

In her introduction to the book, Whitney writes: “As I experienced Lake Erie myself, I discovered that my vision could be complicated and richer for it.”

The photographs document the shoreline from Cleveland to Toledo. Not, she says, a comprehensive view of the lake.

Nor is it nature photography in the purest sense. Rather it is meditation on life and death along the shore. Here a duck decoy is as much a part of the landscape as an actual duck. The lake is presided over by bleached out statues of deities as well as freighters and jetliners overhead. Mansions and mills line its shore. Birders flock to the marshes on its shores.

That’s evident in the first photograph. In the foreground, lies a large dead fish ignored by the people on the shore of Lake Erie that serves as the backdrop. There’s a grandmother and her tutu-wearing grandchild – the youngster’s dress reflecting her dreams. Their dog huddles near the grandmother, seeking shade. On the other end of the log are a couple of birders. She looks intently out over the lake through her binoculars; he seems to be zoned out.

Whitney’s black and white images have a spontaneity that belies the care and time it takes her to capture them. She uses an 8×10 view camera that is “very clear, cumbersome, and slow,” writes her mentor and former teacher Nicholas Nixon in his essay included in the book. “The force of her eye kindly organizes and reconciles, allowing us to really see what we are looking at.”

Her shutter is open, soaking in the image for half a second – not the 500th or 1000th of a second for the average point and shoot image.

The camera itself can be an entrée into the lives of people. They are curious.

“I wanted to feel like I was very present. I didn’t want to feel like I was invisible and that I was stealing,” she said. “You get people’s attention. I wanted my subjects to feel seen. That it is collaborative.”

She recalls making the photograph of two women sitting in a car at Edgewater Park. A colorful detail of one women’s hair caught her eye. She approached them.

The photo has a wealth of incidental imagery. One woman is drinking a Blizzard, and the pine tree shaped air freshener hanging from the mirror also evoke nature.

And then, as Whitney went under the hood of her camera to make the exposure, one woman put her hand out the window as if to check he weather. “When she stuck her hand out, that was picture I wanted.”

The broader context here is that “African-Americans have a very different experience of lakes and parks,” she said.

“So much of my process is about discovery,” she said. “It’s my camera that allows me that access. They know I’m not a thief. They know I’m not someone who would do something they wouldn’t want.”

Whitney wanted the scientific context for what was happening, so she turned to George Bullerjahn, the founding director of the Great Lakes Center for Fresh Waters and Human Health.

“I wanted the history of Lake Erie from the scientific point of view,” Whitney said.

Bullerjahn explains the dynamics of the lake’s environment, and the threats it faces, especially from climate change. Bullerjahn writes: “The lake may seem to provide a limitless source of water stretching past the horizon, but without vigilant management, a tipping point back to the 1970s may soon arise.”

In her essay, scholar and curator Robin Reisenfeld points to an image that pulls together the lake’s present and past. In “Huron Boy, Huron,” a youngster with a Mohawk-style haircut baits the hook of his fishing rod. In the background smoke billows from the stacks of a factory across the bay.

Reisenfeld writes: “The contrast between the young man preoccupied with catching fish and the far-off manufacturing plant metaphorically registers the dissonance between the strikingly divergent methods of human engagement with the regions natural resources. So too, the youth’s sartorial style and sport fishing call to mind the lake’s pre-industrial history when First Nations people resided along its shores and depended on its once-pristine waters, marsh, and woodlands for subsistence through means of fishing, hunting and gathering wild foods.”

A personal tragedy, the death of art historian Dawn Glanz, a friend and colleague shadows the more recent photos.

Glanz was found dead in May 2013, in her home. Many of her friends, including Whitney, and law enforcement officials believe she was murdered. The case was the focus of an episode of “Cold Justice.”

“Her death really had a huge impact on me and our family,” Whitney said. “It was another thread I just sort of wove into the book … the idea that the lake is a female body, and the lake was abused. Dawn was taken advantage of many years before she was killed.”

A photograph taken the year of her death is a haunting visualization of this idea. Whitney thought the arrangement of branches on the beach was a fanciful interior design like those she made on the beach as a child. Then she viewed it under the hood and realized the branches spelled out the word “BITCH.”

Julie Haught, of the English Department, encapsulated its meaning: “The lake is our bitch.”

Then a year after Glanz’ death, Whitney came upon a woman who was her friend’s ‘doppelgänger.” The woman stood surrounded by water, yet watering her geraniums with a small, unassuming watering can.

All these, she writes in her introduction, are stories that are missing from her memory of her grandfather on “The Sea Saga.”

“Generous people in and around the landscape allowed me to use them to share some of those missing stories and in the process confront our collective past and find reasons to hope. At the center of this work is the relationship of land-based life to water and our need for one another on every level.”