Columbus police union said to be blocking investigation

The union that represents Columbus police is saying one thing but doing another regarding possible misconduct during last summer’s demonstrations. Its leader said there shouldn’t be a rush to judge apparent police wrongdoing, but then the union moved to block the fuller investigation that its leader claimed to want.

Such union obstruction in numerous American cities is said to be a major barrier to accountability. And critics say it’s stymieing efforts to clamp down on the kinds of police behavior that sparked last year’s firestorm of protest in the first place.

Keith Ferrell, president of FOP Lodge #9, on June 2 last year told The Columbus Dispatch “I think the whole story needs to be told.” He was referring to an incident that happened a night earlier.

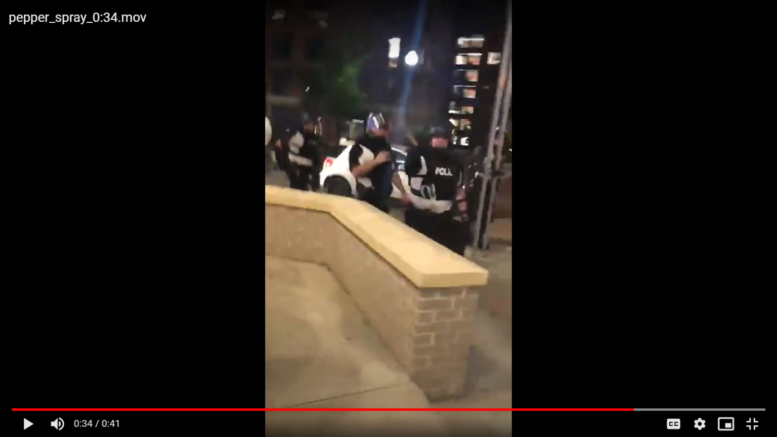

Videos and photos from multiple angles showed three journalists with the Ohio State University newspaper, The Lantern, standing well apart from demonstrators near campus. They were holding up their press IDs and repeatedly telling cops that they were reporters and that Mayor Andrew Ginther’s curfew order allowed them to be there.

Even so, at least one officer pepper-sprayed all three in the face — and one on the back of her neck as she retreated. (Click here to download a video of the interaction.)

More than a year later, the officer still hasn’t been identified, much less punished.

The incident was part of a flurry of police assaults on journalists who were working to cover protests in the wake of the May 25, 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. One officer, Derek Chauvin, was later convicted of murder in that incident and sentenced to 22 years in prison.

As protests broke out in scores of other American cities, dozens of reporters were injured while trying to cover them, many because they were in crowds as police fired rubber bullets and tear gas and used pepper spray. But some, like The Lantern journalists, were attacked as they clearly identified themselves as members of the news media.

The Washington Post called the actions “a blatant violation of constitutional protections and long-standing ground rules that guide interactions between media and law enforcement officials.”

Maeve Walsh, one of the Lantern reporters who was pepper sprayed, said the same.

She and a colleague said the demonstration was peaceful that night until police moved in and started pepper-spraying the crowd — and then the three Lantern journalists who were standing off to the side, observing.

“It really was a blatant suppression of our First Amendment rights,” Walsh said last week. She later added that she doesn’t know what was in the officers’ minds, but “it makes a lot of sense to me that they were targeting us because we were reporters and they didn’t want people to see their actions that night.”

Disobeying orders

The Columbus police union still doesn’t want a full accounting of the evening. Despite Farrell’s statement more than a year ago about the whole story needing to be told, the union he leads continues its efforts to suppress it.

Farrell didn’t respond to questions for this story. But Kathleen Garber, the special prosecutor appointed by the city to investigate the matter, said she’s frustrated.

“There has been a thorough investigation,” she said in an email. “However, the officers at the scene that we can identify have been unwilling to answer (an investigator’s) questions and unwilling to identify the others who pepper-sprayed/were at the scene.”

As they pepper-sprayed the Lantern journalists, police ignored their press IDs and their explanations and told them they had to follow orders. But the same officers are refusing to obey orders from their superiors to explain what happened next.

That raises questions about who is working for whom.

“One of the identified officers was ordered to appear to be interviewed by (the city’s investigator) but filed a grievance, along with other officers who were ordered to cooperate,” Garber said. “That grievance has been set for an arbitration hearing on Oct. 8.”

Ginther spokeswoman Melanie Crabill said the investigation faces “challenges.” She said that despite assurances that they wouldn’t face discipline, only a tiny portion of the cops who were there that night have agreed to speak up.

“So far only five of 60 officers have agreed to sit for interviews — even with assurances that the information they share cannot be used against them (they are witnesses, not subjects),” Crabill said in an email. “Those officers only did so after being given criminal immunity.”

For Sarah Szilagy, another of the reporters who were pepper sprayed by Columbus police, the case is growing frustratingly cold, and she says she harbors growing doubts that justice will ever be done.

“Despite video evidence, despite roster lists of who was supposed to be out there that night, the case rests on officers identifying other officers, which they’re not going to do,” she said. “They’re being protected behind a contract that says, ‘Oh well, these witness officers don’t have to testify anyway; you can’t compel their testimony because it violates our contract.’”

Open season

What happened June 1, 2020, on the corner of High Street and Lane Avenue didn’t occur in a vacuum.

Hundreds of journalists across the country reported being attacked as they tried to document the most widespread public demonstrations in decades — events that clearly qualify as newsworthy.

“Due to the overwhelming number of aggressions against the press made public since protests began, we’re making interim reported incidents available as we investigate them,” the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press said in late October. On Twitter it posted: Latest reported aggressions against the press as of Thursday, Oct. 29 *886+ total press freedom incidents* 120+ arrests 222 physical attacks (160 by law enforcement) 202 rubber bullet / projectiles 102 tear gassings 67 pepper sprayings 91 equipment/newsroom damage 82 other/TBD

It’s not just police attacking the press.

After years of former President Donald Trump decrying critical coverage as “fake news” and calling journalists “enemies of the American people,” the Washington Post last week reported that American TV journalists suffered possibly more attacks in 2020 than in any year on record. And, the paper reported, the trend of violence toward the most conspicuous reporters is continuing.

At least for civilians, some accountability might be on the way. The FBI this month began arresting people accused of attacking journalists and destroying their equipment during the Jan. 6 riot that Trump sparked at the U.S. Capitol.

Ohio Republicans this year have introduced a raft of bills that would give police officers more leeway to go after protesters and the journalists trying to over them.

Scary situation

It’s drilled into journalists that they shouldn’t make themselves part of the story, and the two former Lantern reporters interviewed for this one said they were uncomfortable being on the other side of an interview.

Szilagy described a difficult, volatile situation involving hundreds of people at the protests and feeling there was a professional obligation to tell heavily armed police that their commands were wrong.

“We knew that arguing with police officers doesn’t really go well, so we prepared ourselves to say these things over and over again,” Szilagy, said last week referring to their repeated declarations that they were members of the press and that the curfew order allowed them to be there.

Even with that practice, the encounters were unnerving.

“It definitely was a very intimidating moment,” Walsh said. “I had never been in a situation where I was face to face with a police officer in riot gear threatening me with arrest. That was quite eye-opening. It was very intimidating. There was a lot of adrenaline.”

An officer who initially threatened the three reporters with arrest walked away after they repeatedly identified themselves and held up their press badges. Then a group of police came back and the point-blank pepper spray started, Szilagy said.

“I had an out-of-body experience, but I remember them pepper-spraying me,” she said.

They rushed to a colleague’s nearby apartment to flush their eyes and faces.

“At some point when we were trying to figure out how to write this story about what happened, I noticed that my neck was burning pretty bad,” Szilagy said. “The only way the pepper spray could have gotten so directly on the back of my neck is if they sprayed us again.”

The burns lasted for several days, she said.

During those same days, the reporters faced patronizing police brass who tried to excuse officers’ behavior before they even investigated it.

The first was a public-information officer who claimed that police didn’t know journalists were exempt from the curfew order, despite the fact that the press was second on a list of just four exemptions publicly released by the mayor’s office.

Even more implausibly, then-chief Thomas Quinlan in a press conference claimed police couldn’t tell they were reporters.

As she recalled watching, Szilagy said, “The rage. I had so much anger about it.”

Columbus’s issues with its police union are far from unique.

Officers are given protections against being thrown to the wolves every time they have to make a split-second decision that is easily second-guessed in hindsight. But in numerous jurisdictions, police contracts make it difficult — if not impossible — to even interview officers when they appear to exercise disastrously poor judgment, or worse.

The New York Times last year reported that after civil unrest over police conduct in places such as Minneapolis and Ferguson, Missouri, police unions and their contracts have been major barriers to reform. Lt. Bob Kroll, president of the Minneapolis union, is himself the subject of at least 29 complaints of misconduct, the story said.

Ginther spokeswoman Crabill said the mayor is committed to changing how policing is done in Columbus.

“Last summer, he changed policies on how to use chemical agents in disbanding nonviolent protests,” she said. “He worked to get a civilian police review board on the November ballot and get it passed. The board is now seated and will hold its first meeting in August.

“He has approved new training for recruits to emphasize community policing and is working to get the next generation of body-worn cameras installed. He has also hired a new police chief committed to change and reform within the department.”

But will any of that matter if the police have a contract that protects them from even having to identify who was present during a questionable situation?

In Columbus, the three-year FOP contract is being renegotiated and the mayor’s office is prohibited by law from discussing it, Crabill said.

Szilagy called on city officials to step up.

“The city is incredibly responsible for what happened and it’s their responsibility to prevent it from happening again,” she said. “That means doing what is difficult; fighting back against the real issue — that contract and the power it gives police officers.”