By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Matt Bell knew he had hit rock bottom when he sat in his mother’s garage with a gun in his mouth.

“I just wanted to die,” Bell told an audience at Bowling Green State University Wednesday evening. “The only reason I didn’t pull the trigger is because I didn’t want her to find me like that.”

Bell was one of the lucky ones. Every day in Ohio, eight people die from opiate related overdoses. “Those are good people, who got sucked in,” he said during the program on heroin and opiates.

The opiate problem has been going on for more than a century, according to Andrea Boxill, deputy director of the Governor’s Cabinet Opiate Action Team. But it didn’t seem to matter when Asians used it as they built the railroads across the nation. Or when poor African Americans and Appalachians returned from the Vietnam War using it.

But now it’s different. “It’s the first time it’s affected young, white, affluent people,” Boxill said. Ohio has the distinction of ranking second in the nation for overdose deaths.

Bell was almost one of those statistics. He grew up with an idyllic childhood in a middle class family in Walbridge. “I went to a good school. I got straight As. I played sports. I went to church.” He had a loving family that ate dinner together each evening.

He stayed away from drugs and alcohol and even dumped his girlfriend after he heard a rumor that she had smoked a cigarette.

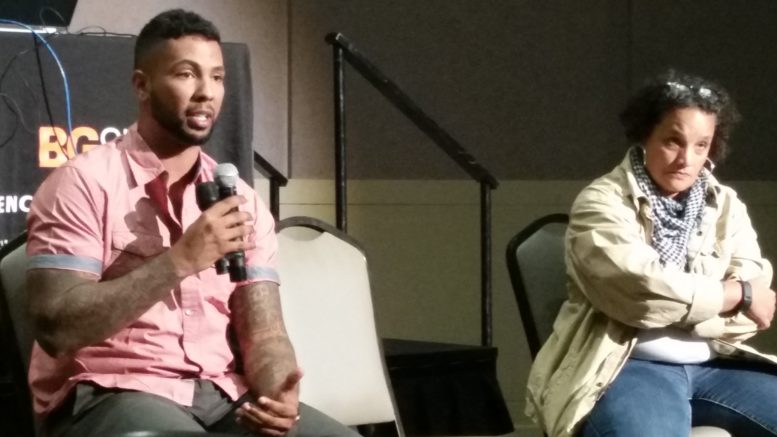

Matt Bell talks about his addiction and recovery.

But then he went from his small school to St. Francis, where there was much more competition. His freshman year, his father was diagnosed with cancer and died six months later.

With Bell’s hero gone, he looked for one elsewhere. It started with a cigarette, moved on to beer, then liquor, then cocaine. The day he got his driver’s license, he got a DUI in Rossford. But he was still able to function well enough to play three high school sports, get at 4.0 GPA, and get a baseball scholarship to University of Toledo.

But one day in college, turning a double play, Bell tore his rotator cuff. The fairly minor surgery would make a major change in his life.

“They sent me home with a prescription for 90 Percocets.”

He took the first one. “I remember thinking – I want to feel like this the rest of my life.”

The pills were gone in a week, between Bell and a few friends he shared them with. Bell was faced with trying to function without that feeling, or buy pills off the street.

“I started buying a lot of pills,” he said. “I graduated from Percocets to Oxycontin.” He was averaging five pills at day, at $50 a pop. At that point, breaking the law meant nothing, as long as he could get the pills.

Then one day, when his dealer had no pills, Bell graduated again, this time to shooting heroin. “I just wanted to feel better.”

Once hooked, Bell explained that withdrawal was similar to a case of the flu – multiplied by 1,000. The pain is indescribable, he said.

Bell shot heroin for nine years. “I didn’t care about eating. I didn’t care about my family. I would do anything to feed my addiction.”

That led to 13 arrests in four states, and being “dead for five days in an ICU,” kept alive on a ventilator.

“I was homeless walking the streets of East Toledo with nothing but the clothes on my back.” He had alienated his family and friends, lost custody of his son, had no job and no car.

Heroin and opiates were not a “choice” for Bell or for any other addict, Boxill said.

“No one chooses the pain of this disease and the isolation that comes from it,” she said. No mother gives up her children for pills. “No, she gave up her kids because she thought she would die without it.”

“I am telling you, it’s a disease,” Boxill said. “And if you think you have been inoculated against this disease, you are wrong.”

Andrea Boxill talks about opiate addictions

Though some like to blame the Mexicans and the cartels, she said, the cause is closer to home. These “drug dealers” come in white coats and oftentimes with good intentions as they prescribe “pharmaceutical heroin” to treat patients’ pain. While few people would accept heroin, “China White” or “Smack” for their pain, they have few qualms about pocketing prescriptions for Percocets.

“These doctors did not seek out to get people addicted,” Boxill said. But an estimated 80 to 90 percent of heroin addicts get started on opiate pain pills, she said.

Part of the problem is that Americans seem to have a real aversion to, and low tolerance to pain. “If you get your teeth ripped out,” it should hurt, she said.

That differs from Boxill’s mom, who declined pain medication as she struggled with cancer. “That generation refused to take medication.” Ward Cleaver, of “Leave It to Beaver,” fame, went to the doctor for cardiac issues. But nowadays, the primary reason patients see a doctor is for pain, she said.

Changes have been made to crack down on over-prescription of pain meds. Emergency rooms no longer hand out 30 pills. Instead, they give a few and tell the patient to follow up with their physician.

“Writing a 30-day script could be writing a death script,” Boxill said.

But the problem continues. In 2014, enough opiates were prescribed in Ohio to give every man, woman and child 62 pills in the state. In all the nations of Europe combined, the number of opiates per person per year is 2.

“We as Americans don’t suffer,” she said.

A map of Ohio in 2008 showed just a few counties shaded in red for experiencing serious opiate issues. By 2013, nearly all of Ohio’s 88 counties were colored red.

“This is considered a health crisis,” Boxill said. And the emergence of illicit Fentanyl, with inconsistent potency, has worsened the crisis.

But positive changes are being made, including a more accepted understanding that opiate addiction is a disease, not a choice. “We can’t continue to shame people who have the disease,” she said. Medication-assisted treatment is being made available, and in some areas law enforcement is help drug addicts get into treatment.

Many EMS and law enforcement officers carry Narcan to revive opiate addicts. Boxill urged BGSU to make Narcan available in residential halls, “putting them out there like defibrillators,” since it’s too late to wait until someone is blue, choking and rolling their eyes back into their head.

The medical profession is also finding other ways to treat pain. After shaking opiates, Bell blew out his knee playing basketball. When he informed the doctors he would not take any pain medications, they were able to find alternatives.

Bell, who overcame his addiction through an area treatment program, is now president and co-founder of Team Recovery, which helps others facing the same disease.

“This is life or death,” he said. “We’ve seen people die on a waiting list.”

Bell also pushes prevention, and spoke at 35 schools last year. Team Recovery also offers family support groups.

“I used to run from the police. I work with them today,” he said.

But Bell knows he will always be addicted and has to stay on guard.

“I know this can creep back up on me,” he said. “As long as I keep doing the next right thing.”