By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

When voters go to the polls next month to vote on the Bowling Green City Schools bond issue, the district wants them to be armed with facts, not motivated by falsehoods.

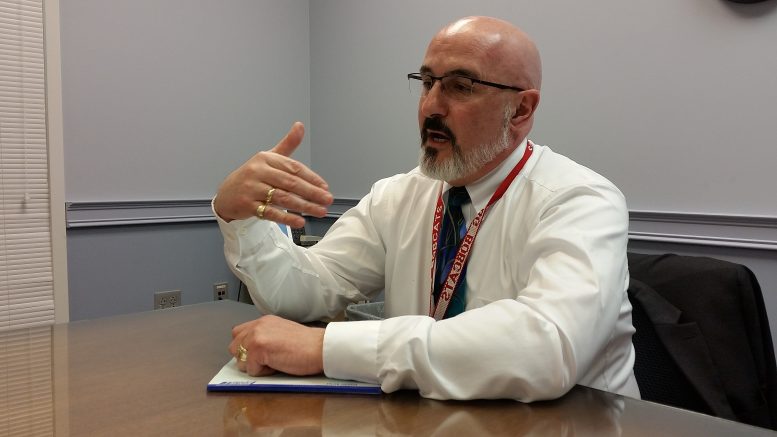

Superintendent Francis Scruci met with local media Tuesday to clear up some misconceptions prompted by levy opposition at recent school board meetings. Scruci said he didn’t address the comments at the time because he considers those gatherings an opportunity to hear from the public – not a time for back and forth debate.

However, when some of those falsehoods were getting traction as fact, Scruci wanted to clear up confusion on the following issues.

Income tax would be a more fair way to fund school buildings.

That may be the case, but it is not an option under Ohio school funding law.

“The county auditor has confirmed you can’t use income tax to build a project,” Scruci said.

During the last school board meeting, it was suggested that the district had twisted those funding rules for the middle school expansion, so it could do the same for the centralized elementary school and high school expansion.

But Scruci explained that the middle school expansion was paid for with permanent improvement levy funds already approved by voters. Permanent improvement funds are allowed to be used for anything with a life expectancy of five or more years.

“I want to make sure people understand,” Scruci said. “It was implied we did something inappropriately.”

Bowling Green City Schools did not turn down any state money for buildings.

“It’s just false that we were offered state money and turned it down,” Scruci said. He considers this myth as one of the big reasons many voters cast ballots against the levy in the fall.

Due to the increased property valuation of the Bowling Green City School District – with much of it being rich farmland – the district is currently ranked 520 of Ohio’s 609 school districts, making it appear the state funds are not needed.

“Because it went up, it makes us on paper look more affluent than we are,” he said.

“We are not eligible and have not been eligible for co-funding from the state,” Scruci said.

The earliest Bowling Green might be eligible is in eight years, and that’s only if school districts in lapsed status don’t decide to get back in line.

Yes, Otsego greatly benefited by 50 percent funding by the state, and Elmwood did even better with 80 percent funding. But Bowling Green isn’t even allowed to get in line yet.

“Many people told us they thought we turned state money down,” he said.

The school district should have waited to go back on the ballot, or should have tried a Plan B.

Scruci has heard this complaint, but he has no reservations about trying the same 5.7-mill levy so soon after it failed last fall.

“When we made this decision, we believed it was the right decision for our district and our kids,” he said.

Trying a watered down version would send the wrong message. “It would tell people we really didn’t need what we asked for the first time.”

“It shouldn’t have been a shock to somebody that we are coming back with the same project – because it is what we need,” he said.

There is nothing extravagant about the elementary or high school plans. They are very similar to the middle school, with “no extra bells or whistles.”

“It is what we need, it’s not what we want,” Scruci said.

Neighborhood schools are a relic of the past.

Scruci realizes that the topic of neighborhood schools can be a hot button issue for some voters. But as an educator, he knows that consistency and equity in resources and opportunities are far more important to learning.

Bowling Green may have had “neighborhood” schools years ago when there were six elementaries. But now there are three, and children travel across town to get to them. Only 10 percent of elementary students walk or bicycle to school.

If the district can’t achieve equity through a centralized elementary, it may consider creating grade level buildings, Scruci said.

The condition of schools matters to the community.

Built in the 1950s and 1960s, Bowling Green’s city schools are the oldest and most antiquated school facilities in Wood County, Scruci said.

“I feel like our students deserve better. I feel like our community deserves better,” Scruci said.

And poor school buildings do have a negative impact on the number of people and businesses that want to move into the district.

“You have to be competitive with the neighboring districts,” he said.

Good schools attract families and businesses, that in turn broaden the tax base, he added.

The school district is not picking on the farming community.

“Do I understand that it impacts the farm community? Absolutely, and that’s not our intent,” he said.

But the district has no other option if it wants to build a new elementary, plus renovate and add onto the high school. Twenty years ago, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that the state’s funding structure for school districts had to be changed. Twenty years later, nothing has been done.

And while some in the agricultural community say an income tax is more fair and they promise support, Scruci said that support has been lacking in the past.

The costs for new buildings will escalate with time.

A standard estimate is that a building project’s cost grows 3 percent with each year it is delayed. So, even on the low side, this $72 million project will cost $82 million in five years.

“We can kick the can down the road, and just put band-aids on it,” but the costs will continue to inflate, Scruci said.

The district could have also stretched the bond issue over a shorter period, since some citizens objected to the 37 year duration of the bonds. But that would have meant higher millage, Scruci said.

The district will see some cost savings.

The school district will cut a lot of expenses if a centralized elementary is built. Those savings have been listed at several meetings – and add up to about $17 million over the life of the levy. That money will go into the general fund, and will help delay the need for more operating levies, Scruci said.

“There’s a return on the investment,” he said.

The new facilities will also help the district retain and attract quality staff.

“It is very tough to attract good teachers if your facilities are subpar,” Scruci said.

Voters wanted more information.

Scruci made more than 100 public presentations about the levy last year, and felt the community had been flooded with information. But people said they want more.

So the district has created a website bgschools4kids.com that has a variety of information about the levy, the building plans, and will help residents calculate how much the levy will cost them. The website should be up by the end of Wednesday.

“We’re trying to make it as easy as possible for people to get a true number,” he said. “We want to make sure they’ve got the correct information.”

“I don’t begrudge people saying they can’t afford it, but I want to make sure people have the facts before they say that,” Scruci said.

The levy lost by 533 votes last November – too close a call to just drop the fight.

“We owe that to our kids. We owe that to our staff. And we certainly owe that to our community,” Scruci said.