By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

(Editor’s note: This story looks at the challenges of online school from the perspective of some Bowling Green City School teachers and principals. A story will follow on the challenges to parents and students.)

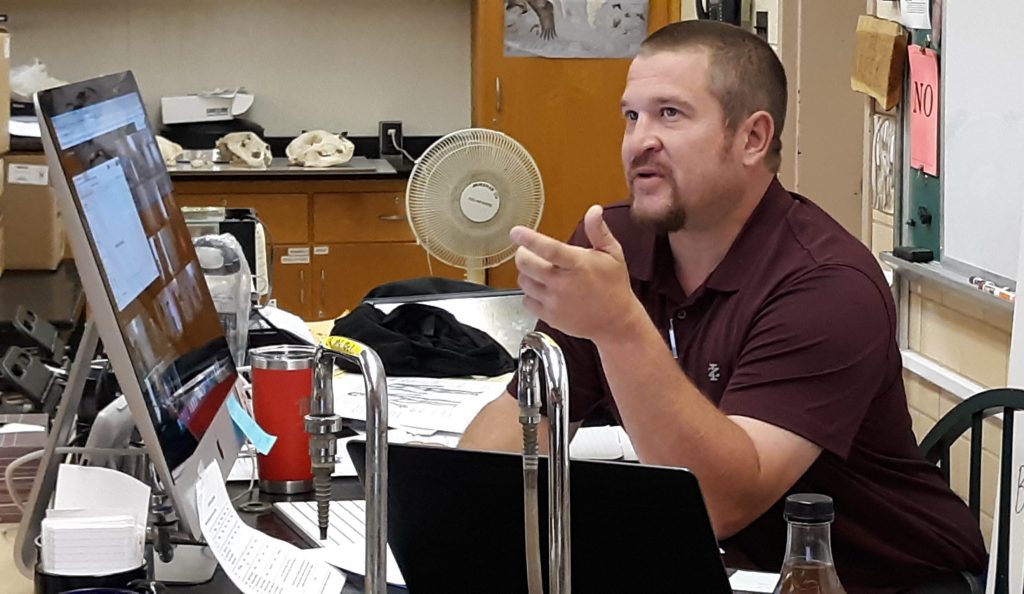

Josh Iler’s classroom at Bowling Green High School offers education through performance art.

So teaching online is a challenge.

“I am such an in-class, in-person teacher. I’m having trouble finding the positives,” Iler said on a recent morning as he sits in his empty classroom preparing for his first lesson of the day.

He is surrounded by bins of bones, taxidermied animals, a Bill Murray poster, and a skeleton next to his desk. All that’s missing are the students, whose chairs are stacked on the desks.

When 8 a.m. rolls around, the majority of his 17 seniors and juniors are on the screen, in varying stages of consciousness. That hasn’t changed with COVID-19. High school students are still groggy early in the morning – and anatomy and physiology take concentration.

So Iler goes into high gear.

He starts with a “round robin” session to review information they already learned.

“How confident are you?” Iler says to one student. The reply – 80%.

“I appreciate the honesty,” Iler says back. He fires off a question about the lumbar region.

“I’ll give you one second. Boom,” he says.

Iler tries to keep their attention.

Why do we shiver and sweat? “It’s like a thermostat in your body,” he says.

“Your hand is a scalpel, and you’re going to do cuts” to answer the next question.

He works to keep all the students engaged.

“Thought you could look away and not get called on,” he said to one teen.

Iler asks a question about the orbital cavity.

“I’ll give you a hint, it’s a sphere on your face,” then he winks.

Then comes the “rapid fire” portion of class.

Again, he asks how confident the student is feeling. “Insanely,” is the reply. But Iler has to correct the answer about the term used for parts of the body further away from the center.

“Not dismal – but distal,” he says.

Then Iler smoothly shifts gears from science to learning.

“You have to have discipline. As a 17-18-year-old, that’s tough. At 40, that’s still tough for me,” he says to the faces on his screen.

“Knowledge is super powerful. It’s going to change your life. And I’m not just saying that because I’m a dorky science teacher.”

“I want you to understand and apply it,” Iler says.

It’s more difficult to know if the students are grasping lessons when he can just see their faces on a screen shared by all 17 in the class. That is one of the biggest struggles for Iler.

“Facial expressions in communication are huge,” he said.

And then there are the occasional glitches with the technology.

“Sometimes the tech works, and sometimes it doesn’t,” Iler said.

High School Principal Jeff Dever understands the reason for online classes right now. But he worries about the teachers.

“I think we’re doing as well as possible,” Dever said. “We’re doing our best under the circumstances.”

The principal is also worried about the kids.

“I feel for our teachers, but I feel for our kids more than anything else,” he said. “Kids need socialization.”

“Hopefully, we can get back to normal,” Dever said.

The challenges are even greater in the elementary schools, where students don’t have those fine-tuned computer skills,and where attention spans are easily lost.

“It’s eerie to be in the building with no kids,” Conneaut Elementary Principal Alyssa Karaffa said as she walked the empty hallways. “We miss the kids. We know this isn’t our best teaching.”

But like Dever, she understands the reasoning for online classes.

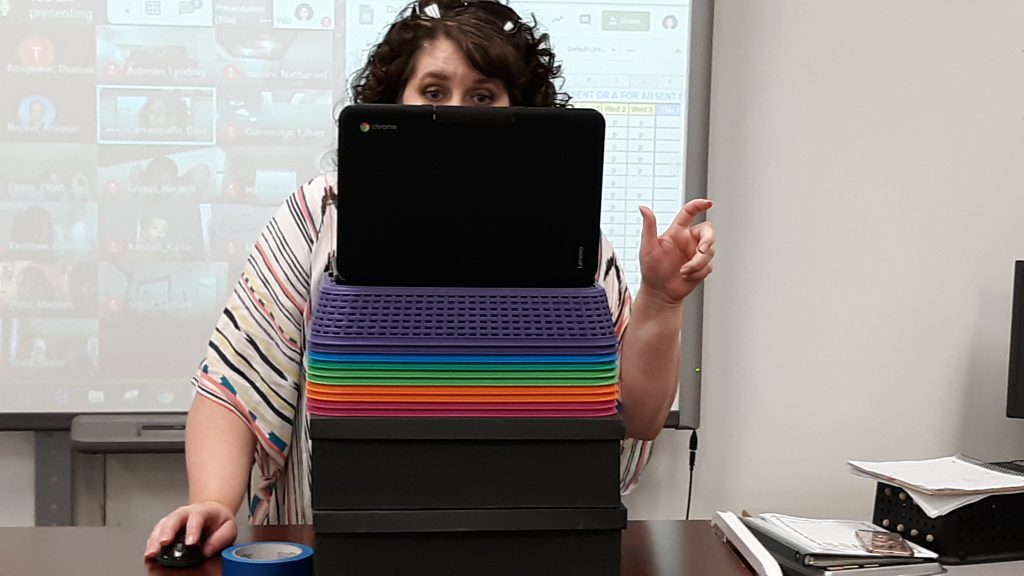

Down the hall from the school office, second grade teacher Danielle Carrasquillo is moving between the multiple devices in her classroom as she teaches a lesson on writing sentences.

All the teachers have to do this, Karaffa explains. They use the school district computers, their personal laptops, headphones and cell phones to teach online.

“Good job everybody, coming back,” Carrasquillo says to her 18 students after they signed in for their third period of the day. She talks about the need for periods at the end of sentences, and capital letters at the beginning.

“We need to use our tall letters when they should be tall, and short letters when they should be short, and hanging down letters when they should hang down,” Carrasquillo says with great expression in her voice.

Then she tackles the more complex issue of sentence structure.

“Sentences should always make sense to our ears and our eyes,” she says.

Teaching these concepts online is tough, Karaffa says as she walks to the next classroom.

“You can sense if a student is getting it, or if he’s sad, or mad by body language,” she said. But the teachers are blind to many of those cues.

“The feedback part is so difficult. That’s how kids learn, and it’s really hard to do on a screen,” Karaffa said.

And right now, teachers can’t give those much needed gentle touches on shoulders to let students know they are doing all right.

In the next classroom, first grade teacher Katie Fields is reading a story to her students. She is wired up to two computers, headphones and a document camera so the children can see the pages of the book as she reads to them.

“Learning how to read, write and do math – that is really hard to do through a screen,” Karaffa explains. “We’re teaching phonics, so we need to hear them and see their mouths.”

At this age, the students often forget to unmute themselves when they talk to the teachers.

“If people think online is easier, they’re crazy,” Karaffa says.

And then there’s the whole tech issue. Despite a stellar technology staff, there are glitches when laptops die or microphones cease to function.

“That’s no fault of the district,” Karaffa says. “That’s the fault of the defunding of education.”

Karaffa has high praise for the district’s technology staff – but problems are inevitable.

“The moment you have tech issues, you’re defeated,” she said about teachers and students alike.

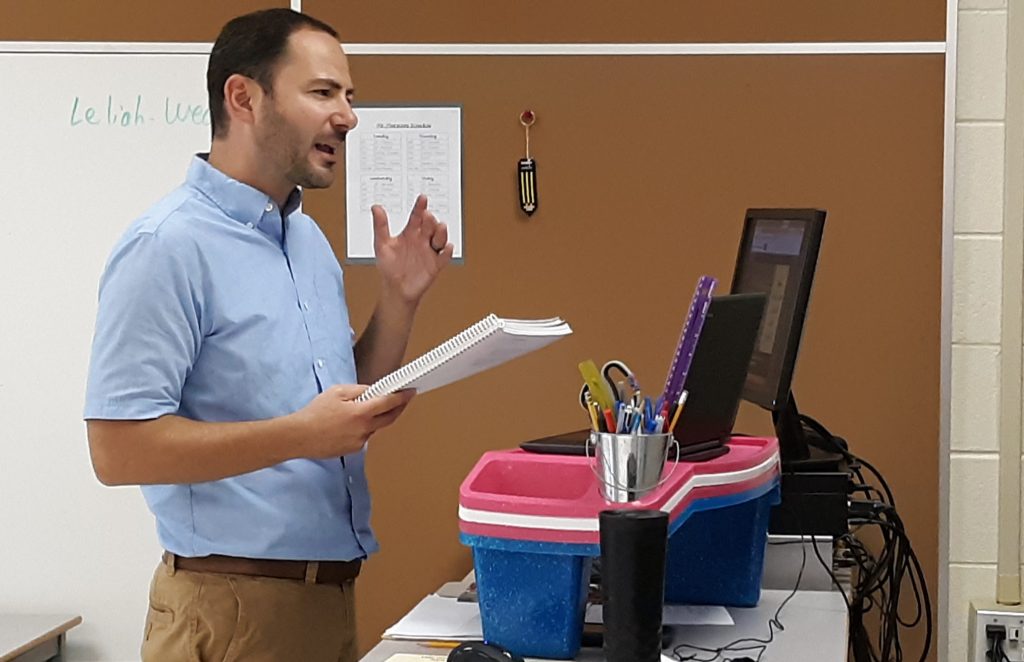

At the end of the other hallway, fifth grade social studies and language arts teacher Bob Marzola has cobbled together his own tech system that works for him. In his animated fashion, Marzola talks to his class about an author. The class is unaware that he is standing at a table stationed on a series of cones so it’s the right height.

The art, music and physical education teachers struggle particularly hard to engage students in learning.

“I know the priority is safety,” Karaffa said, and that a hybrid model of half the students attending school for two days, and the other half in school the next two days may be the next step.

“But nothing is as effective as being here every day,” she said.

However, the online classes this fall are far better than in the spring, when the school had to close in person classes with no notice.

“The spring was more survival,” Karaffa said.

This fall, the online classes offer students a firm schedule and structure. Teachers instruct from their classrooms, with classes starting at specific times each day.

“We want them to still be ‘in school,’” she said (using air quotes around “in school”), where students can see their teachers, peers and classrooms.

Even with just the teachers in the buildings, the custodians are very much focused on stopping the spread of COVID.

“Our custodians are working around the clock, cleaning every touch point, multiple times a day,” Karaffa said.