By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When Brach Tiller graduated from Bowling Green State University just over a year ago, he faced an existential question.

“What the hell am I going to do now? What am I going to paint?” he wondered.

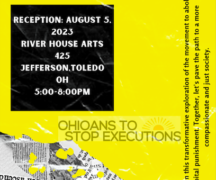

The 26-year-old has spent his first year after receiving his Bachelor’s in Fine Arts degree discovering the answer. What he found is now on display in River House Arts’ Gallery 6, on the sixth floor of the Secor Building at 425 Jefferson on downtown Toledo.

The work he created while studying for his BFA at BGSU was photorealistic with dark and disturbing overtones. It showed the ability to render realistic images in detail.

“I decided it wasn’t providing me what I needed,” Tiller said. So he found himself a studio and began to paint. “I was getting a lot of bad paintings out of the way,” he said. In the past year he figures he’s discarded 30 paintings. While in each one he’d find something to reject, he’d also find some element worth exploring further. That would get worked into the next work.

While engaged in this process, “I was exploring Instagram to see what people were doing in the contemporary art world.”

BGSU as an art school is “a hidden gem,” he said. Still it is isolated from any center of art. So Tiller used Instagram to reach out, as well as to document his own work.

“I had to use Instagram as that tool to find art in the world because you want to be part of the conversation of what’s going on out there.”

Instagram opened up the range of art from the just now to the way back when.

Echoes of those styles started to resound within his paintings. “I’ve started to find things that interest me … finding a reason to keep painting.”

The results are bold acrylic on canvas paintings in pastel colors. The simple shapes, including a pickle like penis, seem to pop off the canvas. The shapes look like they are pinned to the canvas, yet the surface is absolutely smooth. Tiller has not discarded his high regard for detail and technique.

“It’s vastly different than what I was doing a year ago.”

The boldness and the saturated color, while having elements of Op Art and Minimalism, also recall the early 20th century French movement, the Fauvists.

Yet his work, he said, has an intentional artificiality to it, so he created his own term “Fauxvism.”

Tiller’s work has a sense of whimsy, but whimsy with serious intent.

He works part-time as a painter for Life Formations in Bowling Green. Those fanciful figures that magically appear when an amusement park ride enters a tunnel? Tiller paints those.

He uses an air brush. Having mastered the tool at Life Formations, he decided he would employ it in his own work creating absolutely flat, glistening surfaces.

Even with a sculptor as father and a skill at rendering images accurately that was evident from when he first started drawing as a child, Tiller wasn’t headed toward a career in art. For 15 years as a youth, his goal was to be a professional hockey player. He went to Canada to play juniors and played on a team in Michigan. As he approached his 21st birthday and the end of his eligibility to play juniors he pondered his future.

He had offers from Division III schools, but they couldn’t offer athletic scholarships and carried hefty price tags. BGSU gave him a look, but the last time they came out to see him Tiller he had held himself out of the game because he was afraid he was risking losing a year of college eligibility. The BGSU coach passed on him.

Tiller took that as a sign. If his dream of being a pro wasn’t going to be realized, he needed to go in a new direction and focus on the other activity he had shown talent in – art.

He hung up his skates and headed to BGSU’s School of Art.

“I’m really happy things worked out the way they did,” Tiller said.” As much as I loved hockey, I love being in the studio so much more. I didn’t know I could be into something as much as that. I thought I loved hockey. I think I just enjoyed it. I had to come to my love for painting.”

He is still in a state of transition. He lives between Detroit where his girlfriend has moved, his job in BG, and his studio in Toledo. He plans to move to Detroit.

“There’s a lot happening there in terms of art,” Tiller said. Cost of living is inexpensive, and though large, Detroit is still small enough to build a sense of community.

Even in an age of a surfeit of digital images, painting is still important. “Every time people say painting is dead, there’s a great rejuvenation of it,” Tiller said.

He enjoys that he creates by hand images that come from that digital world. “It’s the challenge of putting humanity before the machine. … That makes for an interesting conversation.”

The drive to create is elemental. “I cannot not make paintings.”