By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

For Osamu James Nakagawa photography is a matter of life and death.

Nakagawa bookended his Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar Lecture on campus last week with two images. One showed him still a baby being greeted by exuberant relatives on his family’s arrival back in Tokyo. It was the first time, they’d seen either him or his older brother, both of whom were born in New York City.

He closed with a video of his mother on her death bed, close up images of her last breaths.

Osamu James Nakagawa

This autobiographical streak runs through the photography he showed to the audience gathered in the Fine Arts Center at Bowling Green State University. It does not totally define him though. Nakagawa has won acclaimed for his series of photos of the cliffs and caves on Okinawa where people go to commit suicide. The cave shots are so dark that they barely registered on the screen. He shot them he said at a very slow shutter speed with a flashlight as the only illumination.

Also, he photographed the areas around the U.S. military bases on the Japanese island. They are stark representations of an unwanted military presence that brings crime, including rape, to the province.

Nakagawa studied painting and sculpture in Houston, and then returned to Japan to work as an unpaid assistant to his uncle who was a photographer. To earn some money, he worked with American photographers helping them find the subjects and locations their editors wanted. The lists of requests were always the same – geishas strolling down the street and Mount Fuji. He knew he wanted to photograph what they were missing. He returned to Houston to get a master of fine arts in photography.

In 1998, Nakagawa said his life was a whirlwind. At the time his daughter was born, his father was diagnosed with cancer. The photographer was living in Indiana, where’d he’d just taken a position at the University of Indiana.

“All these things were happening,” he said, “and I was taking photographs. I didn’t see it as a body a work. I needed to slow things down. Things were going so fast. I thought by taking photographs I would slow it down.”

He studied the work of others who made their families the subject of their cameras, including Emmitt Gowin. So he found himself taking baby photographs, something he’d never imaged himself doing. And he found himself taking photographs of his father as he went through chemo therapy, losing 40 pounds, going bald. That, he admitted, was hard.

Nakagawa wanted to take a photograph of his father bathing in the hot springs near the family’s home. It took convincing to get his father to pose naked. His son drew a detailed sketch of the image he wanted. Then his father announced one morning that they should go and take the photograph. It was early, no one would be there. The soft light, Nakagawa said, was perfect.

His father had also bestowed upon him a crate of family memorabilia. Nakagawa brought what he found together for family portraits that spanned decades.

His father had also bestowed upon him a crate of family memorabilia. Nakagawa brought what he found together for family portraits that spanned decades.

One showed his father’s brother heading off to fight in World War II juxtaposed with 8mm home movies of Nakagawa’s family visiting Disneyland, a trip he was too young to remember.

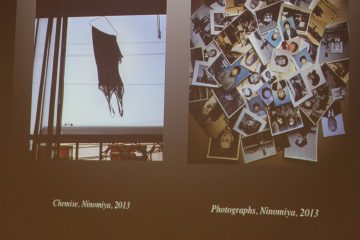

After his father died, Nakagawa continued to photograph his mother as she made the transition from living alone at home where a photo he’d taken of his father leaned against a wall near her bed to residing in an assisted living facility. She resisted the idea and questioned the move even after she’d settled into the facility.

Nakagawa then showed a photo of his mother’s battered face. She had fallen in the facility. Afterward she told him: “If I fell in my home, all by myself, nobody would have found me. This is a good place.”

Later as she was dying, Nakagawa had to frequently travel back to Japan leaving his wife back home with their now teenage daughter. “It’s hard for any couple to go through this,” he said, displaying a photo of his wife, Tomoko, alone in bed.

As he watched his mother die, he took photos, but he realized he needed to catch her breathing. So he videotaped it. “I was out of my comfort zone,” he admitted. The video is uncomfortable for some to watch, he said, before showing it.

It was included in the exhibit “A Shared Elegy” that brought his work together with that of Emmitt Gowin, whose work he admired, and the work of Gowin’s son Elijah Gowin as well as work by Nakagawa’s uncle Takayuki Ogawa. It was Ogawa, his mother’s brother, who took that 1963 photo of Nakagawa’s homecoming. It was another instance of Nakagawa’s work circling back on itself as it records the cycles of life and death.