By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

By mid-June any other year, Gov. Mike DeWine would have been met by knee-high corn and farmers waiting for a healthy harvest in Wood County.

But this year, DeWine instead confronted barren fields and frustrated farmers.

“We’ve had some years that were tough, but not like this,” Perrysburg Township farmer Kris Swartz told the governor on Wednesday.

Four of five of Swartz’s closest neighbors haven’t planted a seed this year.

Swartz, who has 2,000 acres to farm, was intending on planting corn in 700 of them. He got 130 acres in. And soybeans? Well that may depend on the 1.5 inches of rain forecasted for Wednesday night and into Thursday.

“That pushes our soybean planting to July,” Swartz said. Planting so late greatly reduces the chance of producing a healthy crop. “The yield potential is just not there.”

DeWine has already written a letter to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, describing the situation and asking that a disaster be declared for this region.

“I wanted to come here and see this for myself,” the governor said as he stood in Swartz’s wheat field that is struggling with the 54 days of rain since April.

“Certainly the northwest is hardest hit,” DeWine said of the state.

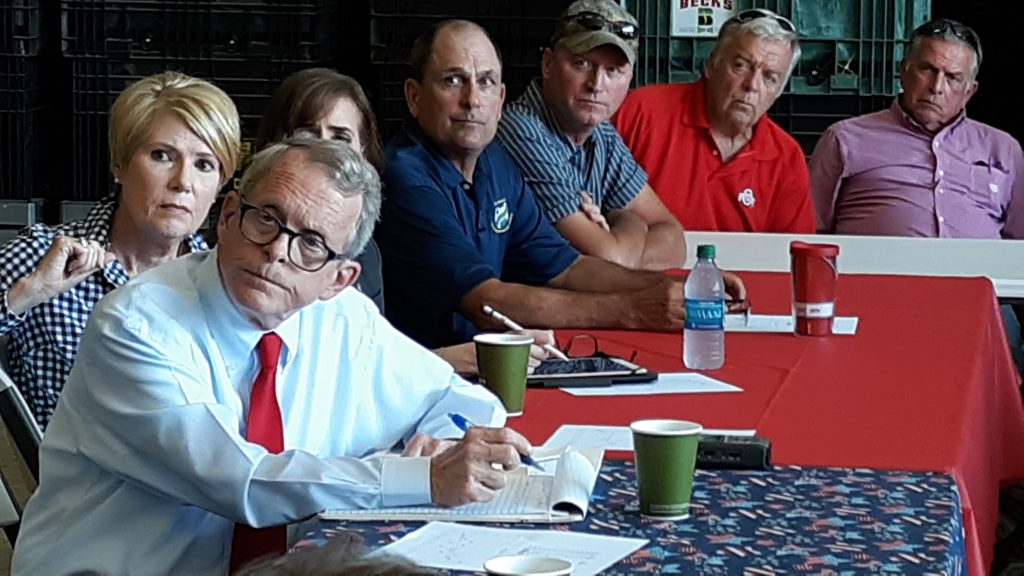

At least 20 farmers from the region came to Swartz’s farm Wednesday morning to tell the governor how dire the situation has become. They came from as far west as Williams County, as far east as Wayne County, and as far south as Hardin County.

The governor was joined by Ohio Agriculture Director Dorothy Pelanda, State Senator Theresa Gavarone, R-Bowling Green, and State Rep. Haraz Ghanbari, R-Perrysburg.

“Driving up here, there was not a single field that was planted. Water is everywhere,” Pelanda said.

The ripple effect of the poor planting season will be felt far beyond the individual farmers, she said. There will be a loss of grain and silage for livestock farmers, there will be co-ops that won’t have grain to process, and there are livestock farmers who haven’t been able to spread manure since last year, Pelanda said.

Very little hay survived the winter, and the wheat is struggling in swamped fields.

“We’re in survival mode,” said local livestock farmer Nathan Eckel. “If we get through this year, what are we going to do next year?”

Mark Drewes, who farms in the Custar area, normally grows corn for local dairies. But he has been unable to get any corn in the ground this year.

“We’ve had drought and wet weather before, but nothing like these historical proportions,” he said. “These cows have to have feed. This is the first time I’ve felt our backs are against the wall.”

The ripple effect will continue further down the food chain. There won’t be sweet corn at roadside stands, the strawberry crop is substantially lower, and prices at groceries can be counted on to rise.

And the impact won’t stop there. One historically horrible year will be felt for years to come.

“It snowballs,” said Lesley Riker. “If we don’t have the seed, what are farmers going to plant next year?”

While farmers are being advised to plant cover crops, some seed for those crops will be hard to come by.

And just forget about crop rotation.

“I think we’ve all accepted this will be a disastrous year financially,” Swartz said. “We’re just trying to make it to next year.”

Then there is the human toll. Family farms that are just hanging on may give up after a year like this, some farmers predicted.

“We’re going to survive, but it’s going to be tough,” Swartz said. “For some of our young people, this could be devastating. We need young people in our industry. I’m afraid we’re going to have too many young people pushed out.”

Older farmers have had time to pay off expensive equipment and land. But the costs don’t stop there, with seed and fertilizer expenses growing.

“To be a farmer today is tough,” DeWine said.

Crop insurance will help, but it’s more like “treading water” than making a living, Swartz said.

Beyond affecting the profits, the poor planting season has led to sunken morale for local farmers.

“We’re kind of like the date that got dressed up for the prom and nobody picked us up,” Swartz said. “The farm community is pretty down. I think it will help them out that the governor is showing interest.”

Several Wood County farmers gathered in Swartz’s barn for a roundtable discussion with the governor.

“We’ve never not produced a crop,” said Brian Herringshaw of the Liberty Township area.

Over in Middleton Township, farmer Shane Vetter has not put one seed in the ground this year.

“We’ve never had a year where we haven’t planted corn – let alone planted nothing,” he said.

So Vetter was hoping to hear Wednesday that DeWine could push for federal help. But the question still remains – “Can it go up the chain to where it matters,” Vetter asked.

Phil Wenig, who has planted 20 percent of his soybeans, and none of his corn, shared those same hopes.

“We very possibly can be done,” with more rain forecasted for Thursday, Wenig said. “I think it’s very important that we are declared a disaster.”

According to Pelanda, a federal disaster declaration would allow farmers to apply with their local Farm Service Agency for assistance. That help would supplement crop insurance, she said.

DeWine assured the farmers he would do his best to help.

“Our job is to advocate to the Trump Administration,” he said. The governor asked the farmers to help him pen a more detailed letter to the USDA, explaining the specific issues they are facing.

“You don’t get anything unless you ask for it,” DeWine said.