By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

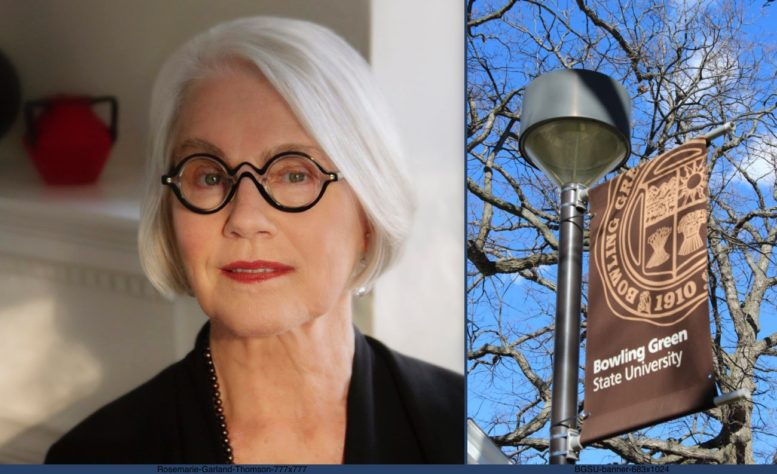

“Disability is everywhere if you know how to look for it,” said Dr. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, a disability justice and culture thought leader, bioethicist, educator, and humanities scholar.

Finding disability is an opportunity to explore, redefine and make new stories about what it means to be human, she said during a recent public lecture at Bowling Green State University.

“Human variations that we think of as disabilities are part of the human condition, and they occur in every life and family. Disability is a set of stories, which is the most unique aspect of my take on disability,” she said.

Disabilities are a part of our culture, history, politics, and aesthetics.

In culture, disability is present in literature, performance, art, and design, and defined as “not so much a property of body but a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do,” she said. She offered many examples. Early literature, such as Sophocles’ “Oedipus the King” is bookended with disability. At the beginning of the book, Oedipus as an infant is found on a mountaintop with his feet swollen from being bound. By the end of the book, Oedipus’ disability is blindness after he gouged his eyes in despair.

Important contemporary American literature where disability is prominent includes Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick,” with Captain Ahab who has a peg leg, and William Faulkner’s “TheSound and the Fury,” whose protagonist, Benjy Compson, has a cognitive disability.

Performance culture finds disability represented in various genres including the music of three African American piano players and singers—Tom Wiggins, Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder—who all performed as individuals with visual impairments. Actor Peter Dinklage, recognized for his award-winning role as Tyrion Lannister in “Game of Thrones” is a person of small stature.

Artists Frida Kahlo and Riva Lehrer depicted disability in their portraits and self-portraits. And Claude Monet’s artwork experienced an artistic evolution as his eyesight deteriorated. “His later works, such as ‘Water Lilies,’ are fuzzier because this is what he was actually seeing,” Garland-Thomson said.

Inclusive design is about rebuilding and remaking the world to accommodate disability and create access within the built environment, she said.

From designs for ramps and building access to individual technologies such as wheelchair and prosthetic limbs, inclusive design has transformed shared spaces and changed the composition of who inhabits the spaces.

“Wheelchairs and walkers have previously been medical equipment designed for sick people tobe used and pushed by others. But all sorts of wheeled mobility has been transformed to be useable by a wide variety of people outside of medical facilities,” she said. The change is obvious in large airports where utility vehicles are now used by able-bodied individuals.

Many of the design changes that have occurred are thanks to the passage of disability legislation that originated as part of the Civil Rights Act in the 1960s. It wasn’t until the Americans with Disabilities Act passed in 1990 that individuals with disabilities were ensured the equal treatment and access to employment opportunities and public accommodations.

Ramps and access routes are much different than the original ramps when architects “ruined the aesthetic and economic value of buildings” by strapping and bolting on ramps to the fronts of buildings. Today, ramps and elevated paths are at the very center of design, creating access everywhere “when you know how to look for it,” Garland-Thomson said.

“Often access, whether it is a ramp, a door push, a tactile watch, does not call attention to themselves, but they make public participation possible. Accessible design and cultural consciousness create inclusion by changing who we share our world with,” she added.

Before the disability rights were enacted, individuals with disabilities did not have access to public schools, public transportation. “You would not have been able to go to school with

someone in a wheelchair because the built environment did not allow many people with disabilities to enter into public spaces,” she said.

Garland-Thomson encouraged individuals, institutions, and communities to understand disability history, culture, and justice, as well as the technologies and accommodations that are available.

“You can practice disability inclusion in the spaces you inhabit, in the workplace, the. marketplace and the schools. If we work together to increase disability inclusion, it can change attitude, increase access, build community, and cultivate leadership,” she said.

A world that includes disability is a world that is better for everyone because it allows more people to share and live together in a caring community.