By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Carol Jacobsen’s photographs and videos of women in prison could have been self-portraits.

In the late-1960s, Jacobsen was in the same kind of situation that landed many women in prison for life,

Right out of high school, she said in a recent interview, she ran off and married her high school boyfriend. “He was a sociopath. He beat the shit out of me,” she said.

So many women in prison, she said, are there because they finally fought back and killed their abusers or were forced or coerced into participating in crimes, and then had to pay for the male partners’ actions.

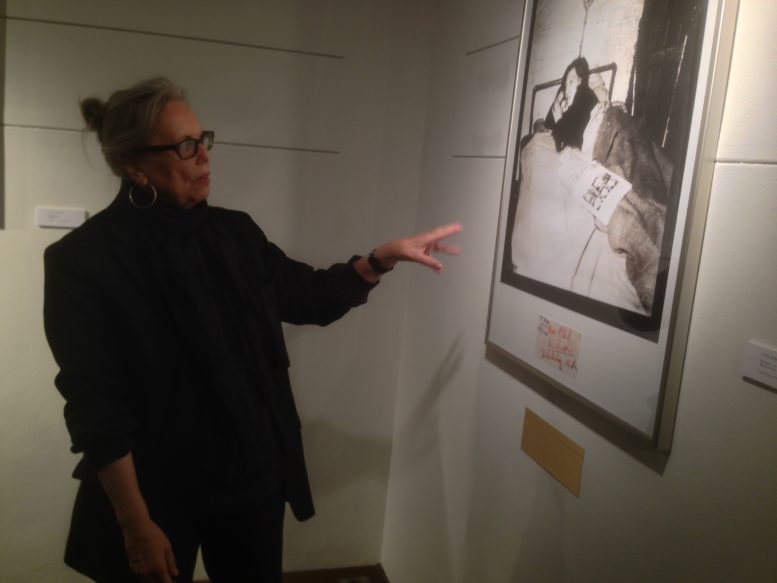

These are the issues she explores in work now on display in the exhibit “Criminal Justice?” in the Wankelman Gallery in the Bowling Green State University School of Art. Her videos explore the lives of those in prison and her photo pieces reflect the continuum of the abuse of women within the criminal justice system. The exhibit also features Andrea Bowers’ video documentary “#sweetjane” about the Steubenville rape case. The exhibit continues through Nov. 20.

These are the issues she explores in work now on display in the exhibit “Criminal Justice?” in the Wankelman Gallery in the Bowling Green State University School of Art. Her videos explore the lives of those in prison and her photo pieces reflect the continuum of the abuse of women within the criminal justice system. The exhibit also features Andrea Bowers’ video documentary “#sweetjane” about the Steubenville rape case. The exhibit continues through Nov. 20.

Unlike the women whom Jacobsen depicts and advocates for, the artist was able to flee her abusive spouse.

“I ran off,” said Jacobsen, who teaches at the University of Michigan. “I had to hide out of town for month. I was pregnant. I was lucky I had family and friends who hid me, and parents who took me to the abandoned building in Detroit for the illegal abortion that I insisted on having to free myself from a violent man.”

When she met the women in prison, she realized: “This could be me; this could be a lot of us.”

Jacobsen went on to study art and earn a graduate degree from Eastern Michigan University. She was inspired to move her work into a political realm, something not permitted at the university, while living in London in 1980. She witnessed political activism and saw “women raising hell in court.”

When she returned to the United States, “I wondered who was disturbing the peace here.”

She went to district court in Detroit, and at first focused on the plight of prostitutes, mostly poor, black women. Their punishment by the state and stigmatization by society was a nexus of the feminist issues – abortion, rape, and battering, domestic abuse.

Her idea was to follow some of these prostitutes when they went to serve time on prison. Once in prison, she met other women, women serving life sentences. “These are the murderers?” she asked. They were doing time for the crimes of their boyfriends, or for defending themselves.

“I got hooked,” Jacobsen said. She decided to integrate legal activism into her art. She collaborated with a couple attorneys and together they formed the Michigan Women’s Justice and Clemency Project.

Under the auspices of the project she would go inside the state’s prisons, and film the inmates and record their stories. Then in the late 1990s, Gov. John Engler closed off the prisons. All filming was banned. Visitation was limited to immediate family and legal counsel.

The move was made because the Michigan prison system had been cited as one of the worst in the country by the U.S. Justice Department, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and the United Nations. They documented medical neglect, sexual abuse and rape in the prisons. “Human rights abuses are rampant especially in solitary confinement,” Jacobsen said, where many have mental illness.

“It’s unbelievable what goes on because it’s such a closed system,” she said. “They refuse them food, refuse them water, tie them down naked to the bed, to cement slabs.”

The works on display at BGSU include a diary of a prisoner, read by Jacobsen over footage of the outside of the prison. The inmate talks about a baby being born in the facility on a filthy mattress and about an inmate who committed suicide. She been in for 34 years “and was in so much pain.”

The woman writes in the diary: ““Being here is very much like being in an abusive relationship. After a while you can’t tell anymore when you’re being abused.”

Other works juxtapose images of incarcerated women from the archives of a defunct Cleveland newspaper with damning quotations from contemporary trials. In one, the judge states: “Why should I not conclude that you are a danger to society because you suffered such horrendous abuse?”

When these women go to court, they are at an insurmountable disadvantage, Jacobsen said. “The rules of evidence don’t allow people to present the full case, so they’re left with no defense.”

The resources available to the prosecutor far outweigh what’s available to the lawyers appointed for the defense.

“Prosecutors have too much power,” Jacobsen said. “They’re accountable to no one. They’re re-elected based on the notches on their belt.”

After 25 years she concludes: “Our defense system is worthless. … It’s really an imbalanced system. We think you’re innocent until proven guilty, but the reverse is true.”

Jacobsen’s most recent work focuses on the case of a woman who killed her rapist and was sentenced to life in prison. The clemency project was able to get her out after 23 years, she said, and was able to change state law “forcing the judge to give full instructions to the jury in a self-defense rape case.”

Jacobsen said she hopes that 100 years from now Americans will look back in horror at what happened in its prisons, the same way they look back at the tortures inflicted upon people in medieval time, “because we do torture.”