By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

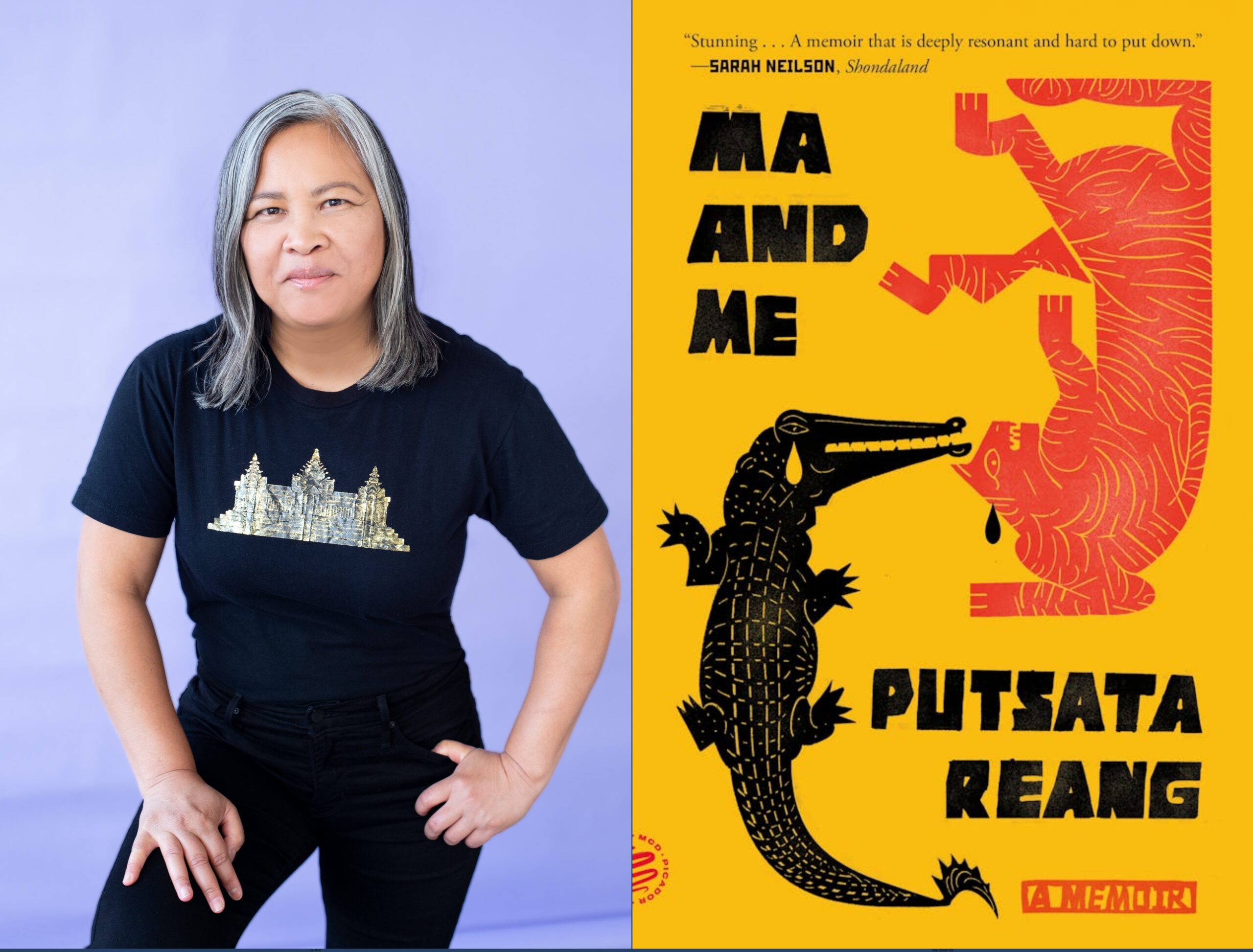

Putsata Reang has told countless stories as an author and journalist for publications such as The New York Times, Politico, The Guardian, Ms. and The Seattle Times. It was a story her mother told about carrying Reang’s lifeless body as an infant from war-ravaged Cambodia to a naval base in the Philippines that defined her storyline for decades and became the premise of her 2022 memoir, “Ma and Me.”

As the keynote speaker on Tuesday for Bowling Green State University’s celebration of Asian, Pacific Islander, Desi American (APIDA) Heritage Month, Reang said her origin story told over and over again by her mother shaped their relationship and her life.

The story Reang heard repeatedly began in Cambodia, where a family–Reang’s family–got on a boat when the country’s civil war “arrived on their doorstep” in 1975. The decision to leave or be killed by the communist regime of Khmer Rouge “completely changed the trajectory of their life.”

The family of six, including mother and father, an eight-year-old daughter, six-year-old son, two-and-a-half-year-old daughter and an infant, ran to the docks and secured a spot on a boat that took them first to safety in the Philippines and eventually asylum in the United States.

The trip was long and arduous with no destination in mind or itinerary of how long they would be at sea. Ten days into the voyage, Ma became worried when her baby stopped crying, eating or moving.

The devoted mother refused the captain’s suggestion to toss the “dead baby” overboard. Instead, when the boat docked at the naval base in the Philippines after 23 days at sea, Ma ran to the Red Cross hospital, where the baby received fluids and medicine and was alive. Ma’s determination had saved the baby, and the baby, who later was diagnosed as a failure-to-thrive baby, was Putsata.

“Imagine the baby in the story. She doesn’t know who she is or who she will become. But she’s going to grow up hearing this story – her origin story about that baby on the boat,” Reang said.

“When you hear a story repeated so often, you start to believe it. The story metabolizes you, and you get trapped by the story, cornered and caged by the way the world perceives you,” she said.

The lesson she took away from hearing the story incessantly was that she must spend the rest of her life of trying to be worthy of her mother’s rescue.

“And that’s what I did. I began to live my life to make my mother happy,” Reang said.

That failure-to-thrive baby became fully dependent on her mother. “Our lives were so intertwined, I didn’t know where her life ended and mine started,” she said. “I spent my life trying to repay that debt.”

Her mother’s hopes and dreams for her included being a good student and eventually being a good wife to a husband. Reang tried to make her mother happy and proud, but early on she knew she was different. Not only did she look different from the mostly white students in that Corvalis, Oregon, classroom, but she also felt different.

“I was suppressing something inside me that was screaming for air. The truth was I was gay,” she said, understanding that being gay was not a good thing in Corvalis or in her family.

She recalled she first had feelings for a girl who lived down the street. They laughed and played together and became fast friends. In high school, an inadvertent touch of hands that sent an electricity through her confirmed in her mind that she was gay.

Reang was ashamed at the thought of being gay, so she pushed her feelings down.

Eventually, she saw that her mother’s story didn’t have to define her. Instead of allowing her origin story to cage her, she was determined to rewrite the story.

Instead of her mother being her savior, Reang gave herself credit for fighting to live when she was on that boat.

Writing the 386-page book was her way to tell the story “of hardship and hope…but also of limitation, vulnerability and weakness,” she said.

Stories play such an important role in identities, but “we don’t need to carry a story that is unbearable,” she said, referencing poet Joy Harbo’s philosophy.

Through writing the memoir, Reang learned “We don’t need to live by the narratives that others have given us; we can rewrite that story.”

It takes courage to discover the truths beyond the stories that others tell.

”We have to imagine a life and a role for ourselves beyond the stories that other people have for us or the stories we carry ourselves,” she said.