By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

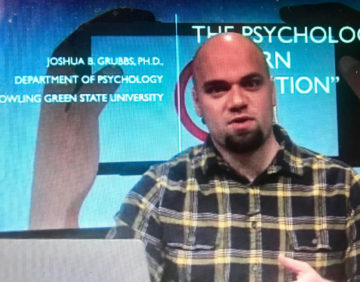

Growing up in the Bible Belt, the son of a Baptist preacher, Josh Grubbs encountered young men concerned they were addicted to pornography.

After graduating from Liberty University, he went to Case Western where he earned his doctorate in psychology and began his studies in behavioral addictions, both gambling and sexual behaviors.

Studies confirmed that young men from conservative religious backgrounds were more likely than their peers to seek help for addiction to porn. That’s despite data showing evangelical Christians are less likely to consume porn.

What gives?

Researchers attribute this to “moral incongruence.”

Grubbs delved into “The Psychology of Porn ‘Addiction’” during the January virtual Science Café presented by BGSU’s Division of Research and Economic Engagement.

The quotation mark on “addiction” in the program title is telling.

Pornography addiction is not a recognized diagnosis. Only very recently has compulsive sexual behavior disorder been accepted as a diagnosis.

“Some people seem to have problems because they’re viewing a lot of porn,” he said. “They are actually out of control.” And this has disrupted their lives.

“But other people think they are addicted to pornography because even though they think it’s wrong, they do it a little bit, and they feel really guilty and really ashamed about doing this thing that violates their morals. And that makes them think they have an addiction even though they’re not doing it at a level we would consider addictive. That’s what we would call pornography problems due to moral incongruence.”

Grubbs continued: “What we’re not trying to say here is that people with religious values just feel really guilty and they should just feel better about using porn.”

He’s also not contending that there aren’t people whose use of porn and whose sexual behavior is out of control.

That is “a real thing,” he said. “Both of these are still real problems.”

Whether someone is experiencing moral incongruence or actual compulsive behavior, it still takes a toll. They are more likely to feel anxious, to be depressed, to have problems in their relationships, and to be unfulfilled in their religious and spiritual life.

These are real problems, Grubbs said, that cause a lot of pain and distress, and it’s appropriate for people to seek mental health help for them.

More and more people are. Close to half of mental health providers have treated someone concerned with their use of porn and their sexual behaviors. On college campuses about 80 percent have treated someone for this disorder.

“We know a lot of people are quite concerned about their use of porn and their sexual behavior, that they might be addicted to sex,” Grubbs said. A survey found that 7 percent of women and 11 percent of men “feel like they might be out of control.”

Not, he said, that they are all “addicted.”

Before 2010, little research was done in this area. Grubbs said his career has coincided with the spike of research.

That increase in research comes during a period of growth in online porn. “Pornography is the biggest single form of media on the internet,” he said.

Children have cell phones with data plans making it all the more accessible.

While 40 years ago, it may have been a stack of Playboys in someone’s garage, now they can see extreme behavior. That’s why, Grubbs said, protections are needed.

Does this lead to a greater risk of sexual disorder later?

“I don’t think we have the data we need to understand that,” said graduate student Jenny Grant Weinandy.

Shane Kraus, a professor from the University of Nevada Las Vegas who received his doctorate from BGSU, said that the lack of data on that question “is a concern.”

Studies have shown that in other behaviors, such as smoking, drinking alcohol, drug use, vaping, and gambling, that early exposure leads to a greater likelihood of problems later.

That this proves to be such a “robust indicator” for so many other behaviors leads Kraus to assert “as researchers we should be thinking about that.”

Grubbs said “the bigger question is what does it mean for sexual development for children and adolescents. … More broadly what is it doing to what children and adolescents think is normal sexuality. Perhaps it’s nothing negative, perhaps it’s a lot of negative.”

More studies on this are being done in Europe, he said. In the United States, “there’s not a lot of funding for this, especially in adolescent populations.”