By ROBIN STANTON GERROW

for BGSU Office of Marketing & Communications

As the Western world sees a new influx of immigrants, many with strong religious affiliations, countries are grappling with how to help them acculturate into their new societies.

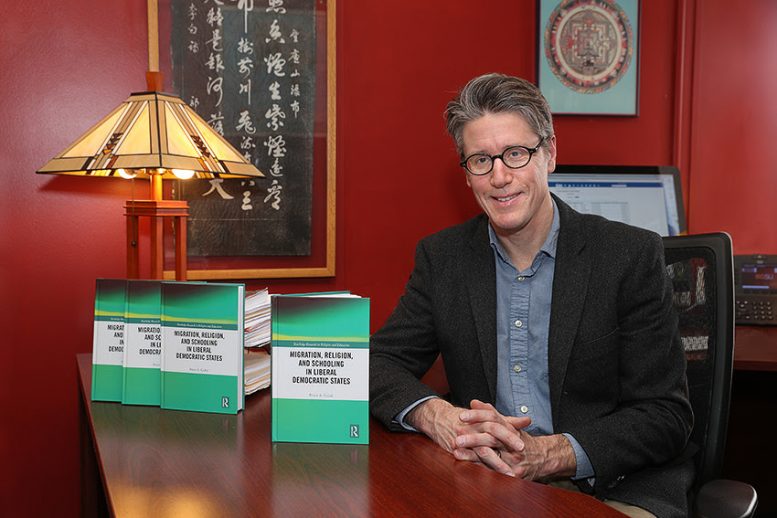

Dr. Bruce Collet, associate professor in the Bowling Green State University School of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Policy and coordinator of the Master of Arts in Cross-Cultural and International Education program in the College of Education and Human Development, sees the important role public schools have in this process. In his new book, “Migration, Religion, and Schooling in Liberal Democratic States” (Routledge, 2018) he lays out recommendations on how these institutions can help facilitate immigrants’ integration.

Drawing from political philosophy, the sociology of migration and the philosophy of education, Collet argues that public schools in liberal democratic states can best facilitate the pluralistic integration of religious migrant students through adopting policies of recognition and accommodation that are not only reasonable in light of liberal democratic principles, but also informed by what we understand regarding the natural role religion often plays in acculturation.

Collet posits the question of how public schools in liberal democratic states — those that place a high value on freedom and autonomy — can help immigrants and refugees create a “sense of belongingness” to their new homes.

“It really is about how educational policymakers and teachers can better understand the connection between religion and acculturation,” he said.

Collet’s interest in this issue stems from a combination of scholarly work and personal experience.

“My parents were emblematic of the 1960s,” he said. “They wanted to throw off the constraints of the ’50s. We moved to Madison, Wisconsin, when I was 7, and the journey for them was spiritual in a way not available to them when they were growing up. At a very early age, I saw the connection between migration and faith, as my mother, who was involved in the Quaker movement, worked with Central American refugees. Later, for my dissertation, I worked with Somali immigrants in the Toronto area on the relationship between the migration experience and perception of a national identity. Working with the Somalians, generally a religious lot, I found that religion surfaced as an important element of the diaspora and it piqued my curiosity.”

For his current work, Collet found that religion can sometimes be front and center, either as an impediment or facilitator of integration into a new culture.

“Schools in liberal democratic states have a vital role to play in helping migrant students integrate into their new society, and it is important that they begin by understanding how and where migrants feel they ‘belong,'” he said.

“Religion, not always, but often, will play a positive role in selective acculturation of new immigrants,” he said. “One way is through institutions—such as churches, temples, and mosques—as points of entry for social networks and employment, and to provide an anchor or sense of security for immigrants.”

But how can public schools become part of this integration process in which religion is so important? According to Collet, one thing policymakers can do is begin to truly understand the importance of a child’s religion, and not just accept it.

“Take, for example, a first-generation Muslim girl from Yemen who wears a hijab,” he said. “We may allow her to do so, as our society values the free expression of religion. But we don’t have an understanding as to why it is important to her identity, why it gives her a sense of security, so I’m hoping that the book will contribute to the conversation and why it matters for many children.”

Better understanding of the religion of new immigrants can steer policy leaders toward addressing issues that are important, such as praying spaces, dress codes and even instruction about religion to help non-immigrant students better understand their immigrant and refugee peers.

In the book, Collet also looks at how autonomy and independence impact immigrant students.

“One of the grounding principles of a liberal democratic state is freedom — which could include the ability to question, and sometimes leave, a religion,” he said. “We value that as a core facet of being a member of a democratic state. We can ask: Can one be religious and autonomous? When given the opportunity to learn about other religions, it can give migrant students a chance to examine their own religion more objectively.”

“This is all part of the American story,” he said. “So many American families have been through this. Migrant are frequently a religious group, and we need to understand that religion and integration are not incompatible. We also need to address the mythology that immigrants who hold fast to their cultural and religious identities will fragment American society — we have to look at the evidence, which often points in the opposite direction. Integration does not mean giving up one’s cultural, religious and linguistic backgrounds. However, integration does require the participation of migrants in their new society, which in this case means embracing the fundamental principles of equality, key individual freedoms and the freedom to realize one’s autonomy.”

While working on the book, Collet served as a Visiting Research Fellow at the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford, and has discussed his findings at universities in the United Kingdom and China.

“It has been so interesting to hear how audiences from different parts of the world and cultures have different concerns,” he said. “Just fascinating to hear the variety of questions people have based on where they are located.”

He’ll have a chance to put some of his recommendations into play a little more locally, as he is working with the North Olmsted City Schools on a grant to fund a teacher professional development project drawing from several ideas presented in his book.

“It will involve a series of workshops, including student storytelling in a district that has a large immigrant community,” he said. “The teachers are working hard, but it is often out of their wheelhouse. This work will inform the workshops and put the recommendations into practice.”