By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Amanda Gamby’s new job may fall short of being glamorous. It’s had her tagging garbage bins, going through recycling, and riding bike for the first time in eight years.

But as Bowling Green’s first ever sustainability coordinator, Gamby doesn’t mind getting her hands dirty. She is a true believer in the city’s environmental sustainability – whether that involves energy production, recycling, bicycling or clean water.

Gamby, who spoke Thursday to the Bowling Green Kiwanis Club, said the city has already made some serious strides toward sustainability.

“We’re really already doing some pretty cool things,” Gamby said. “We’re just not telling about it very well.”

So that is part of her job. Gamby, who previously served as the Wood County environmental educator, has expertise in public outreach and education for very young children to senior citizens, and everyone in between.

And she wants them all to know that 42 percent of Bowling Green’s electricity comes from renewable sources.

“That’s a pretty big chunk of the pie,” Gamby said.

The city was the first in Ohio to use a wind farm to generate municipal electricity, starting in 2003.

“The joke is that it’s a wind garden because it’s only four,” she said. But even though it’s just four turbines, some doubted the city’s wisdom and investment in the $8.8 million project.

“Many people thought Daryl Stockburger was crazy,” Gamby said, of the city’s utilities director at the time who pushed for the wind turbines.

But the turbines have been generating power ever since.

The turbines are as tall as a 30-story building and generate up to 7.2 megawatts of power — enough to supply electricity for approximately 2,500 residential customers. Debt on the wind turbine project was paid in full in 2015, which was several years earlier than planned, Gamby said.

And now, the city is home to the largest solar field in Ohio.

The 165-acre solar field consists of more than 85,000 panels and is capable of producing 20-megawatts of alternating current electricity. In an average year, it is expected to produce an equivalent amount of energy needed to power approximately 3,000 homes. It will also avoid approximately 25,500 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year since the energy is generated from a non-fossil fuel resource.

The city is also talking about building a community solar field on East Gypsy Lane Road, where city residents and businesses can buy into solar power.

“We’re really leaders. Our small community is setting the stage for others,” Gamby said.

Bowling Green city officials have been adamant that the wind farm and solar field be open to tours so that others can learn from the alternative energy sites. Tours are allowed under and inside the turbines, and through the rows of solar panels.

“That’s pretty unheard of in the industry,” Gamby said.

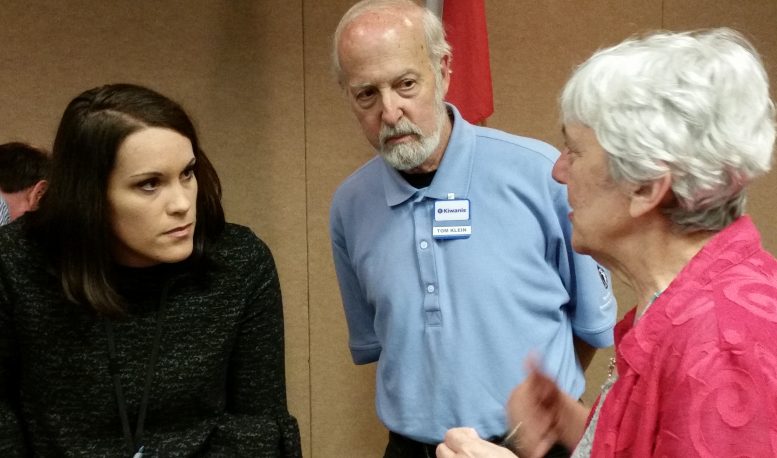

John Calderonello talks with Amanda Gamby, Bowling Green sustainability coordinator.

The city is working to improve some of its other environmentally friendly programs, like encouraging more “rain gardens” and educating people to not put pollutants into storm sewers since stormwater is not treated by the water pollution control plant.

Bowling Green continues to try to educate residents about its curbside recycling program, in order to keep contamination out of the recycling bins. But the city – with its frequently changing population at BGSU – finds the job can be rather repetitive.

“To educate those students on an annual basis is a unique challenge,” Gamby said.

Many residents think they are being helpful by bagging up plastic bottles or newspapers in plastic grocery bags. But those bags get tangled in the recycling machines and are automatically thrown out since the items inside can contaminate the recyclables if the bags are full of garbage instead of plastic or papers.

“They think they’re helping,” Gamby said. “But I can tell you, if a bag comes across the line, it’s thrown away.”

The city is working on a partnership with BGSU on an electronic program called “Recycle Coach.” The App answers questions such as what items are accepted for recycling and when they are picked up.

“We’re really excited about trying something fresh and progressive,” she said.

Gamby said Bowling Green has several “green” benefits that many take for granted. She mentioned the 100-plus-acre nature preserve at Wintergarden Park and the Slippery Elm Trail.

“That’s pretty unique for a small community like ours,” she said.

The city employs an arborist and has earned the designation of Tree City USA for 37 years, plus the program’s “growth award” for 23 years.

Bowling Green is also working to make bicycling in the community easier and safer.

“We’re trying to approach biking from more of an education standpoint,” she said. “We want our residents and students to safely navigate the city.”

But Gamby acknowledged there is an “us versus them” attitude in the community between bicyclists and motorists. So bicyclists are being trained about their rights and responsibilities, and motorists are being reminded that they are legally required to share the road.

“There are folks in our community who that’s their only mode of transportation,” she said of bikers.

The city is hosting monthly bike rides that have been attracting between 40 and 45 riders.

When asked why more local festivals don’t have recycling containers, Gamby said “event recycling” is lacking everywhere, not just in Bowling Green. But she said the Wood County Solid Waste Management District has a lending program that will give out the recycling containers for free.

She was also asked what happens to plastic grocery bags that are returned to grocery stores. A Kiwanis member said he tried to find out, but was told by a local grocery that it was “proprietary” information. Gamby said she would be glad to look into that issue.

After the meeting, a member questioned why City Park did not have containers for recyclables. Gamby said the city did put recyclable containers in the park, but removed them because too much trash was put into them.

Gamby said she often hears the rumor that recyclables are dumped at the landfill.

“I can promise you they’re not,” she said, noting that it costs $40 a ton to dump items at the landfill. “If they’re landfilling it, it’s because it’s trash.”