By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Before the Europeans arrived in what they considered the Americas, there were no Indians nor Native Americans.

There were, however, human beings of ancient lineage who had lived in this “New” World in a multitude of nations and tribes. There are 574 federally recognized tribes of indigenous people in the United States, as well as others who have not been recognized.

Seth Thomas Sutton, who teaches visual and critical studies at Montcalm Community College in Michigan, spoke at BGSU last week about how the “Indian,” or rather the image of the Indian came about and how it persists in the popular imagination.

Sutton is Odawa/Métis from the Wolf Clan Little Traverse Bands of Odawa Indians.

He introduced himself as a fellow human being. “We are all related.”

All people have experienced colonization, he said. All were at some point members of tribes. “We’re taught to have amnesia about these things,” Sutton said. These layers of assumed identities need to be stripped away so we can recognize our common humanity.

As a scholar and student of language, Sutton critiques language. But society now sees critiquing as dangerous. “Criticism is not a bad word,” he said. “Part of our power is take the language and the words we use, take them out twist them slightly, stick them back in so we can regain how we use our language, so we can begin to focus our energies and focus our powers.”

In “politically correct” times, people stumble over how to properly use that language. But if “I have big chunks of stupid fall from my mouth” that is just a learning experience.

What’s right “Native American” or “Indian”? Neither exist, Sutton said. Neither term ever had a basis in reality. Those terms refer to people who existed long before those terms were coined. They are concepts built on fallacies. Those concepts must be deconstructed and removed so indigenous people can regain the energy and agency they lost through colonization.

The image of the “Indian” has taken shape starting with the Spanish invasion of what is now the Americas. “The ‘Indian’ is an accumulation of simulations and representations,” Sutton said.

Those are found in the Declaration of Independence which speaks of “the merciless Indian savages.”

That construct of the Indian takes shape and is refined in dime novels, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, and western movies, which he noted are the largest genre of film with over 7,000 movies, well ahead of the 2,000 war movies, the second most popular genre.

Artists and photographers contributed to the image. Though painter George Caitlin and photographer Edward Curtis claimed to be documenting indigenous people, they cultivated the stereotypes by dressing and posing their subjects based on what their viewers expected to see.

The image is based on tropes featuring images of people with long hair, dark complexions, buckskin, beads, and feathers. Some indigenous people may look like that, so that just confuses this issue, Sutton said.

This accumulation of stereotypes and caricatures have transcended actual reality. People are no longer able to differentiate between the make believe image and reality.

Those images have embedded themselves into pop culture in the form of sports team mascots. These images give fans something to share and rally around, a sense of solidarity that Sutton terms “visual communion.”

They also strip indigenous peoples of their ability to shape their own identities, based on their present lived experiences.

Sutton noted with approval the de-naming of the Washington football team and the Cleveland baseball team.

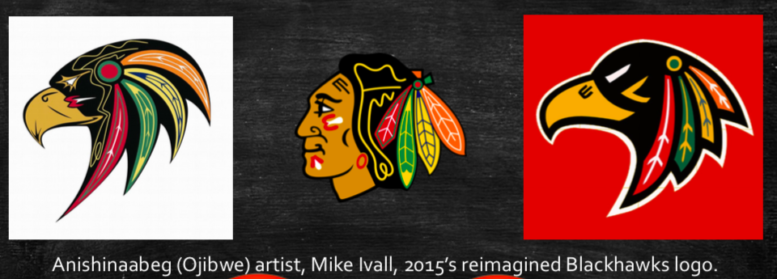

(Image provided)

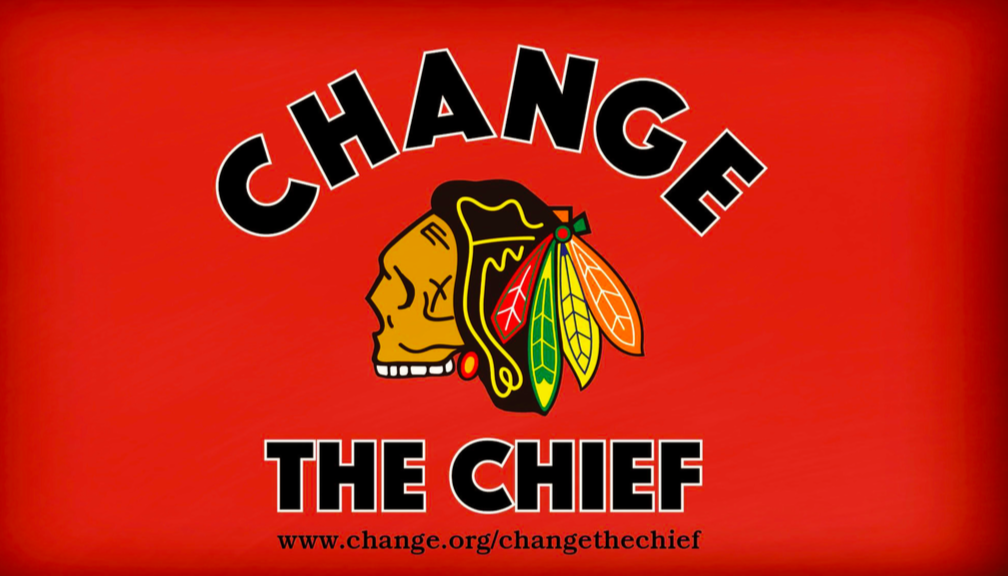

But why, he wondered, have hockey’s Chicago Blackhawks seemingly gotten a free pass?

Sutton has made getting rid of that mascot his mission. Last year he published “The Deconstruction of Chief Blackhawk. A Critical Analysis of Mascots & The Visual Rhetoric of the Indian.” He has also launched an online campaign at change.org.

The case of the Blackhawks is actually easier than most. The founder of the team, Frederic McLaughlin, named his team for the U.S. Army’s Blackhawk Division, in which he served during World War I. But that name did not refer to Blackhawk, the Sauk leader and warrior, whom the hockey team supposedly honors. The division’s shoulder patch depicted a hawk. The original image of a chief was drawn by McLaughlin’s wife, the famous ballroom dancer Irene Castle.

The transformation should be simple, Sutton said. The name should return to being two words in reference to the swift predatory bird.

Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) artist Mike Ivall has designed a logo of a bird that retains the color scheme, outline, and even the feathers of the existing image.

Sutton’s talk was the first in the university’s In the Round: a six-part speaker series featuring Native American Creatives. The series is a way of elaborating on the university’s land acknowledgement statement. The next event will be a presentation by author Carole Lindstrom and illustrator Michaela Goad of the Caldecott Award-winning book “We Are Water Protectors,” on Friday, April 1, at 5:30 p.m.