By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

After nearly 20 years of fighting big agriculture in Ohio, a handful of Wood County citizens scored one victory over “factory farms” in the state.

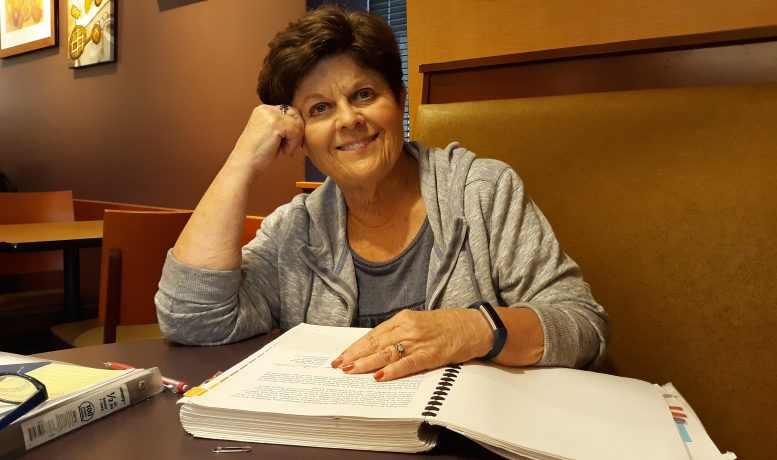

Vickie Askins, who leads the small group of strong-willed citizens, knows better than to expect their victory to make a big difference.

“If nothing else, this will expose what is going on,” Askins said.

The triumph came last month in the form of a reprimand from the U.S. EPA Inspector General, saying the citizens’ petition filed in 2011 cannot be ignored. The petition claimed that the Ohio Department of Agriculture had illegally assumed authority to issue permits for concentrated animal feeding operations of 700 or more head of livestock.

In 2000, the state legislature passed a bill at the urging of the Ohio Farm Bureau, to transfer authority for regulating these large farms from the OEPA to the ODA. But no authority was ever granted by the U.S. EPA for that authority to be handed over to the ODA.

The request was the first of its kind in the nation – a highly controversial move because the ODA is also in the business of promoting the state’s agricultural industries, including the livestock industry.

Critics call that the bureaucratic equivalent of the fox watching the hen house.

To Askins, it made no sense that big agriculture could decide that the Ohio EPA should no longer have control over CAFO permits.

“We filed a lawsuit,” she said of the group led by herself, her husband, Larry, and Jack Firsdon. The suit suggested that if such a shift in authority is granted, that it must get the permission of the U.S. EPA. That was 19 years ago.

“They still have not,” sought that permission, she said.

Then in 2011, the citizens filed a petition over the same issue.

“We asked them to take that authority away from those folks,” Askins said of their request to the U.S. EPA.

But Askins and the other citizens got no response to their petition – for eight years. The U.S. EPA Inspector General said that delay was unacceptable.

“At least the inspector general revealed something is going on, and is saying that something must be done,” Askins said. “If nothing else, this is going to force Ohio to do something.”

The primary issue, according to Askins, is that the U.S. EPA is in charge of the Clean Water Act. But under the ODA, the large livestock farms are being allowed to place more manure on their lands and the acreage they contract with than is healthy for waterways – and Lake Erie.

ODA has issued many permits for “factory farms” containing millions of animals. Waste from these animals has been identified as a major source of the nutrients fueling Lake Erie’s yearly harmful algal blooms.

Pointing to a major loophole in ODA’s permitting program, Askins talked about the “distribution and utilization” method for manure which allows animal waste to be sold by “factory farm” operators to third-party “manure brokers,” with little accountability for what eventually happens to it.

“The farmers are getting blamed for this,” Askins said of sending too many nutrients into Lake Erie that lead to harmful algal blooms.

But the majority of crop farmers are complying with the state’s standards, and have cut in half their nutrients that they place on their fields.

Sewage treatment plants and industries have made updates so fewer nutrients reach the state’s waterways. Phosphates are banned in detergents, and are no longer used in most lawn care products.

Meanwhile, Askins said, the CAFOs can continue to put the same amounts of manure on their fields – and on the fields that they contract with for manure placement.

“And look what’s happening, the farmers are getting blamed,” Askins said.

“Anytime you put thousands of gallons of liquid waste on a field in Wood County, it’s going to come out the tiles,” she said. “Is anybody watching this?”

The manure applications from CAFOs go largely unmonitored, Askins said.

“We don’t know where they are putting it, or how much they are putting on,” she said.

The accidental activist

This is not how Askins planned on spending her retirement, after completing 32 years at Marathon. She had no idea that her life would be filled with filing requests for public information, filing Freedom of Information requests, putting together a petition with more than 200 pages of documentation, and meeting with government officials.

“This was not in our retirement plans,” the accidental activist said.

Askins had no way of knowing that before it was over, she and her husband would have filled 30 big Rubbermaid boxes and three four-drawer file cabinets with data on the CAFOs.

When the first CAFO moved into Wood County – the Manders Dairy near Weston – Askins didn’t pay much attention. But when the second one was proposed – the Naomi Dairy near Cygnet close to her home – Askins shed her retirement for activism.

She was one of the first citizens in the county to caution the Wood County Commissioners about the effect the CAFOS may have on the former Great Black Swamp.

“Some people think we are anti-agriculture – but we’re not,” she said, explaining that she and her husband were members of the Farmers Union for 15 years.

“This is not a good place for liquid manure,” she said. “We’re not just trying to cause problems here.”

Adkins said she is also not opposed to the Dutch families who moved here to operate the large dairies for Vreba-Hoff.

“They came over with the best of intentions,” she said.

Since those first two, other CAFOs have moved into the county. There is the Reyskens Dairy near Custar, and the MSB (formerly the Green) Dairy in Portage Township. That is the largest in the county, with an estimated 2,960 cows, she said.

Though the Dutch families managing the farms are well-intentioned, Askins accused the Vreba-Hoff company overseeing them of corruption. The company is the target of many lawsuits in several states.

In Wood County, the company was found to have altered information on its permit requests, sometimes changing elevation data, floodplains locations, and manure discharge information, she said. In some cases, the farms make sure they have one fewer livestock than the 700 minimum, so they don’t have to adhere to CAFO rules, Askins said.

Over the years, their strong opposition to CAFOs has pit “neighbor against neighbor.” And it has cost them financially, with their organization spending more than $100,000 over the years for work such as water testing by the dairies.

The local group opposed to the CAFOs started out with around 200 members, then dropped down to 100, then 50, then 25, and is now about six die-hard members.

Initially, Askins was shocked that citizens had to fight so hard for clean water and reasonable regulations of the CAFOs.

“We assumed the ODA was on our side back then,” she said. “But big ag is like fighting the government. They are so powerful.”

Askins is no longer surprised – but she is still troubled.

“Why are we being forced to fight this? Our agencies ought to be doing this,” she said. “It amazes me we have to fight our own government. We all need clean water. It doesn’t matter what your political party is.”