From NOAA COMMUNICATIONS

NOAA and its research partners are forecasting that western Lake Erie will experience a smaller-than-average harmful algal bloom this summer. A relatively dry spring will lead to a repeat of last year’s mild bloom – this is the first time in more than a dozen years that mild blooms have occurred in consecutive summers.

This year’s bloom is expected to measure 3, with a potential range of 2 – 4.5, out of 10 on the severity index – among the smaller blooms since 2011. Last year’s bloom was measured at a 3. The index is based on the bloom’s biomass – the amount of algae – during the peak 30 days of the bloom. An index above 5 indicates more severe blooms. Blooms over 7 are particularly severe, with extensive scum formation and coverage affecting the lake. The largest blooms occurred in 2011, with a severity index of 10, and 2015, exceeding the scale and measuring at a severity index of 10.5.

Lake Erie blooms consisting of cyanobacteria, also called blue-green algae, are capable of producing microcystin, a known liver toxin, which poses a risk to human and wildlife health. Such blooms may result in economic impacts for cities and local governments that are forced to treat drinking water, close beaches and prevent people from enjoying fishing, swimming, boating, and visiting the shoreline, and harm the region’s vital summer economy. These effects will vary in location and severity due to winds that may concentrate or dissipate the bloom.

“Communities along Lake Erie rely upon clean, healthy water to support their community’s well-being and economic livelihoods,” said Paul Scholz, acting deputy director for NOAA’s National Ocean Service. “The Lake Erie harmful algal bloom forecast is another example of NOAA’s ongoing efforts to provide timely, science-based information to water managers and public health officials as they make decisions to protect their communities and visitors.”

The size of a bloom isn’t necessarily an indication of how toxic it is. For example, the toxins in a large bloom may not be as concentrated as in a smaller bloom. Each algal bloom is unique in terms of size, toxicity and ultimately its impact on local communities. NOAA is actively developing tools to detect and predict how toxic blooms will be.

Bloom expected to be later and more patchy

With cool lake temperatures in May and early June, the cyanobacteria are currently present only at low concentrations. NOAA expects a more typical start of the visible bloom in mid-to-late-July. While the bloom typically produces some toxins, we cannot predict how toxic the bloom will be when it starts. Even with a small bloom, calm winds tend to allow the bloom to form patchy scums which can concentrate toxins near the lake’s surface, and possibly near the shore. The duration of the bloom depends on the frequency of September wind events, which cannot be predicted this far in advance.

The bloom will remain mostly in areas of the Western basin. The Central and Eastern basins of the lake are usually unaffected, although localized blooms may occur around some of the rivers after summer rainstorms.

“Thanks to our partnerships with governmental agencies, academia, and state research initiatives like the Ohio Department of Higher Education’s Harmful Algal Bloom Research Initiative and Governor DeWine’s H2Ohio initiative, we are continuing to address the challenges of harmful algal blooms from all angles, ranging from providing Ohioans with safe drinking water and studying toxin impacts on human health and food safety, to nutrient runoff prevention,” said Christopher Winslow, Ph.D., director of Ohio Sea Grant and Stone Laboratory.

The Lake Erie forecast is part of a NOAA Ecological Forecasting initiative that aims to deliver accurate, relevant, timely and reliable ecological forecasts directly to coastal resource managers, public health officials, and the public. In addition to the early season projections from NOAA and its partners, NOAA also issues HAB nowcasts/forecasts during the bloom season. These forecasts provide the current extent and 5-day outlooks of where the bloom will travel and what concentrations are likely to be seen, allowing local decision-makers to make informed management decisions.

“Both last year and this year, relatively mild rainfall in the spring has led to less phosphorus being carried into the lake, which means smaller blooms,” said Richard Stumpf, Ph.D., NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science’s lead scientist for the seasonal Lake Erie bloom forecast. “While this is good news, the concentration of phosphorus still remains the same as recent years. Until we begin to see reductions in the concentration of phosphorus, the next year with above-average rainfall will have a more severe bloom.”

Gathering data, refining models

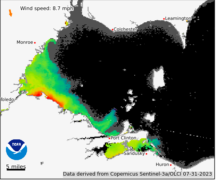

NOAA now routinely uses high-quality satellite imagery from both of the European Union’s Copernicus Sentinel-3 satellites, which were designed to detect blooms in large lakes and estuaries. While this imagery is critical to the forecast model, it only shows how concentrated the algal bloom is on the surface of the lake. The cells that cause the bloom can float and sink in the water, allowing them to move to sunlight near the surface and collect nutrients through the water column. The newly updated Lake Erie Harmful Algal Bloom Forecast website provides more accurate predictions and visualizations of where the bloom is located within the water column. This information is especially of interest to water treatment plant operators because intake structures are usually located below the surface, so the risk of toxins in their source water may be greater when these cells sink.

Nutrient load data for the forecasts came from Heidelberg University in Ohio, and the various forecast models are run by NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, the University of Michigan, North Carolina State University, LimnoTech, Stanford University, and the Carnegie Institution for Science. Field observations used for monitoring and modeling are done in partnership with a number of NOAA services, including its Ohio River Forecast Center, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, and Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research, as well as Ohio Sea Grantand Stone Laboratory at The Ohio State University, The University of Toledo and Ohio EPA.