By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The shadow of ISIS and American politicians who exploit its atrocities hung over the panel on Islamophobia at Bowling Green State University Wednesday afternoon.

The moderator Susana Pena, director of the School of Cultural and Critical Studies, started the discussion off by positing a definition: “Islamophobia is a hatred or fear of Muslims as well as those perceived to be Muslim and Muslim culture.”

She told the more than 100 people in attendance that at its most extreme Islamophobia expresses itself in physical violence and hate crimes, such as the 2002 attack on the Islamic Center in Perrysburg.

It also expresses itself in racial profiling and “micro-aggressions … every day intentional and unintentional snubs and insults,” Pena said.

Cherrefe Kadri, a Toledo attorney, was on the board of the Islamic Center of Northwest Ohio when the arsonist attacked. The man convicted of the crime wrote a letter of apology. “It was a cathartic exercise,” Kadri said. “He thought we were happy he was imprisoned. I assured him we were not.”

Kadri said she is disappointed in politicians such as Donald Trump and Ben Carson who “think it’s courageous speaking against people based on their religion.” And she’s disappointed in other political leaders, especially Republican leaders, who have not opposed their views. “It puts people in danger.”

Saudi student Adnan Shareef, president and founder of the Muslim Students Association at BGSU, said he knows of some Muslims “afraid of affiliating themselves with anything Islam.”

This is especially true of women who may forego wearing traditional head covering. “They are afraid of hate crimes,” he said. “They stop speaking out about their religion and themselves.”

Pena said later in the program that it’s not just up to Muslims, or other members of “marginalized” communities. Putting the burden exclusively on Muslims or African-Americans or members of the LBGT community to explain their experiences also “can be an oppressive move.”

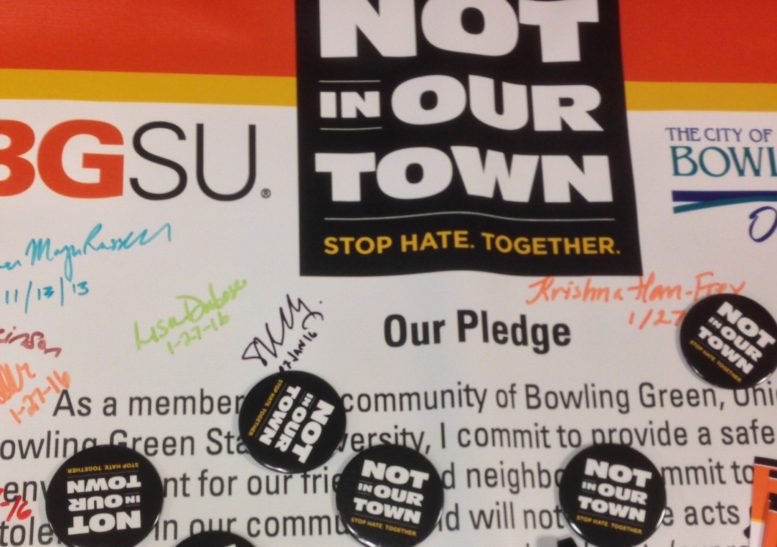

“Some days you don’t have it in you,” Pena said. “The philosophy of Not In Our Town is not to put it on the marginalized community but that it’s everybody’s responsibility… to speak up.”

“Be overt in your support,” said Sgt. Dale Waltz of the Canton, Michigan, township police. “Be a little loud in support of those being discriminating against.”

When incidents happen “don’t just sit in the background, reach out to your Muslim friends, the Muslim community. Let them know you support them and ask them what they need.”

The township 30 miles west of Detroit has two mosques, two Sikh temples and a Hindu temple, he said. In 2008 a police lieutenant, who is now the public safety director, initiated the founding of Canton Responds to Hate Crimes, even though the community had seen few such incidents.

The idea, Waltz said, is to engage the community and that even seemingly small incidents of prejudice or somebody “spewing racial hatred” are worth addressing.

Recently one woman wearing a hijab walking near a local restaurant had someone passing in a vehicle shout at her “go home.”

Her response: “You mean five minutes from here?”

Another elderly woman was accosted in the grocery store.

Actions need not lead to legal action, he said. Rather they help to spot more widespread issues that need to be addressed.

“We make sure everybody has a voice in the community,” Waltz said.

Also representing Canton, where a Not In Our Town group was recently formed, was Library Director Eva Davis.

The library, she said, is a neutral place where all are welcome. While Canton’s population is 30 percent minority, half the library’s patrons are minority.

The library offers a place people can meet, and share their concerns. People realize they have the same hopes and dreams for themselves and their families.

Khani Begum, who has taught English literature at BGSU for 26 years, has long incorporated books by Indian, Muslim or Middle Eastern writers in her courses.

Before 9/11, she said, she offered a course on Middle Eastern women writers. The course addressed the sensitive subject of women wearing the veil.

Two Iraqi women, twins, were enrolled in the course. One of the women wore her hijab, the other didn’t. “They were able to help me teach,” Begum said, about the philosophy and rationale behind wearing the hijab.

“When students encounter students from diverse parts of the country or diverse parts of the world, who have different religious or cultural perspectives, that’s a better way for them to learn. The resistance is not as strong as when one person comes in as the teacher and tries to teach them.”

They respond to that as teaching handed down from the ivory tower. “These women saying that this is Islam to them makes a bigger impact on them.”

Panel attendee Jarvis Hill, from Northwood, said in his travels and study, he knows that Mohammed, the founder of Islam, wanted to bring peace to warring tribes. ISIS, he said, represents a resurgence of that “tribal warfare.”

“ISIS hates the Muslim who don’t practice their flavor of Islam more than they hate non-Muslims,” Kadri said. ISIS has killed more Muslims than non-Muslims.

Another attendee praised local business owner So Shaheen for his efforts to help a family recently immigrated to the United States from Peru. He gave the father a job and lent the family a car among other acts of assistance.

Shaheen said that the charity done by Muslims in the community is often lost.

“Whenever you hear Islam the image is ISIS with a knife on someone’s neck,” said Shaheen who owns Southside 6 in Bowling Green.

“Nobody focuses on the charity we do. … Nobody looks at us as individuals and what good we do in the community.”

Not In Our Town will present another panel on Islamophobia Feb. 9 at 6:30 p.m. in the atrium of the Wood County Public Library in Bowling Green.