By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

As the face of the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. knew the movement depended on the ordinary people marching beside him.

“The beautiful and terrible truth is that King was no more, and no less, than a powerful figurehead of many interrelated efforts, which were organized and enacted by ordinary citizens,” said Dr. Jolie Sheffer, from BGSU, during the annual King tribute in Bowling Green on Friday.

So Sheffer dedicated her speech to King and the ordinary people who stood beside him – the lawyers and teacher, actors and politicians, sharecroppers and college students, who were black and white, poor and rich, queer and straight, Northern and Southern.

“On this day, let us also honor the tens of thousands of volunteers from across the United States, whose names have been forgotten, but whose efforts were crucial,” she said.

“Their individual contributions may not have been memorialized in famous speeches or by photographs, but the movement was built on their efforts,” Sheffer said.

The “ordinary heroes” knocked on doors to register people to vote, organized carpools during bus boycotts, and made phone calls to organize marches and sit-ins.

“They kept working long after cameras stopped rolling,”she said.

Now revered as the face of the Civil Rights Movement, King was not always heralded as the champion of equality.

“The truth is that in his own time, King was hated and feared by whites across the country,” Sheffer said. In 1966, a Gallup poll found that 72 percent of white Americans had an unfavorable opinion of King, she said.

The stories told today about the Civil Rights Movement often imply that change was inevitable. That perspective glosses over the daily grind of the work and uncertainty about the outcome.

“The history of the civil rights movement that we usually learn is a fable that distorts and obscures the more beautiful and terrible truth by making change seem inevitable and turning Martin Luther King into Santa Claus and Rosa Parks into a tired old lady,” Sheffer said. “The reality is that change is never inevitable; it must be fought for.”

And the fight continues – with the outcome unknown.

“While our laws may have changed, our institutions continue to apply the law profoundly unequally to the poor, to people of color, to people with mental illnesses. The work is not complete,” Sheffer said.

And white people must take a bigger share of the burden in the continuing fight.

In his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” King wrote of his frustration with white moderates, many who never felt the time or the tactics were right to push for change. King wrote of white moderates as being a bigger stumbling block than the Ku Klux Klan.

“The time is always ripe to do right,” Sheffer said quoting King. “The moment to act against injustice is always now. The moderate’s call for patience does not make anyone’s lives better – for indeed, justice delayed is justice denied.”

Injustice continues, she said, listing the issues of mass incarceration, income inequality, LGBTQ rights, disability rights, women’s rights, climate change, refugee and immigration policies and Islamophobia.

“And so today, I say – especially to my fellow white people – that it’s on us to participate in this generation’s human rights struggles,” Sheffer said.

In the decades that have passed since the Civil Rights Movement, many white Americans have convinced themselves that they would have been on the right side of history.

“I hate to break it to you – that’s just a comforting fiction,” she said.

The vast majority of white people, in the North and South, opposed integration.

“The truth is, unless we proactively work to change these systems, we are no different than those white people who stood by and did nothing while they watched black protesters on television being attacked with dogs, sprayed with fire hoses, spit on, beaten and worse,” Sheffer said.

Sheffer challenged the audience to actively “do something.” While worthwhile, teaching tolerance isn’t enough. Intervening as a bystander isn’t enough.

Rather than being an ally, go a step further and become a “co-conspirator,” she said.

“I ask you to think about how you can conspire with others to tear down the systems that are unjust and inequitable.”

She urged people to get involved in organizations like Not In Our Town and La Conexion.

“I am talking about doing more than just being nice or neighborly,” Sheffer said. “Use your voice, use your authority to speak up for those who aren’t in the room when decisions are being made.”

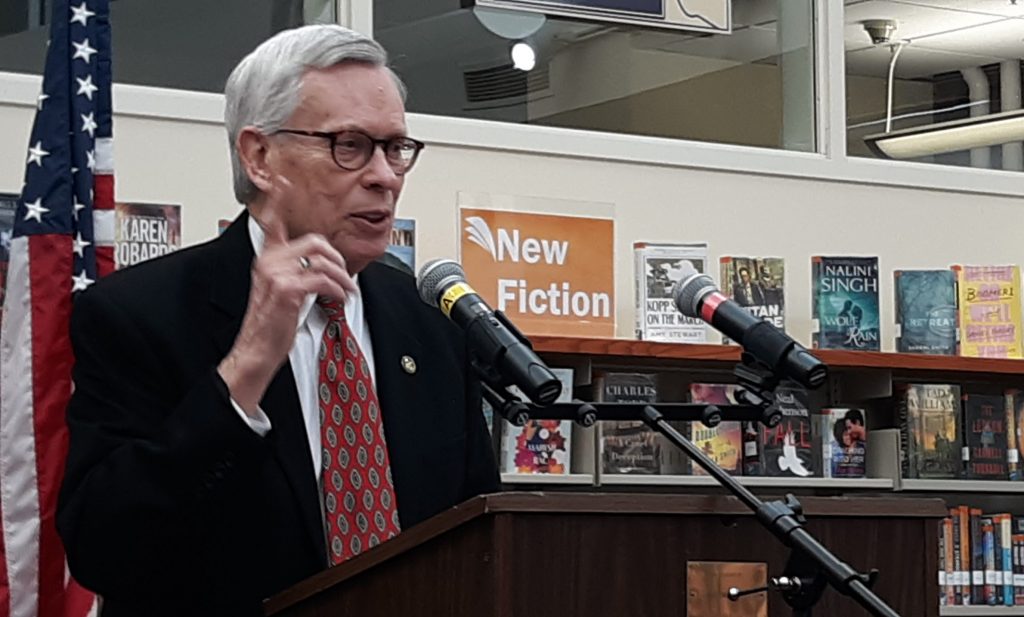

Also at the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. tribute, the Drum Major for Peace Award was given to Mayor Emeritus Dick Edwards. The award, named for a line in a 1968 speech of King’s, is presented annually to a person who has significantly bettered the community.

“I have come to have a profound respect for him,” Rev. Mary Jane Saunders said of Edwards, whom she has served with on the city Human Relations Commission for nine years.

“We don’t live in a perfect world. And ours is not a perfect city. But we are trying,” Saunders said. “Mayor Edwards has been a tireless companion on the way to the promised land.”

Saunders listed Edward’s effort to create Not In Our Town, the Welcoming Community initiative, and the Interfaith Breakfast.

“He said he would support it only if all the faiths in our community are included,” she said of the breakfast.

“We will all remember you in the community for your compassion and your sense of justice,” Saunders said to Edwards.

Human Relations Commission member Ellie Boyle introduced Edwards, telling of his time working for a congressman in Washington, D.C., during the Civil Rights Movement. She shared how Edwards witnessed the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – an event he would never forget.

As he accepted the award, Edwards said he was touched by the honor.

“It is so important that we come together as a community for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,” he said.

Edwards praised the efforts of the Human Relations Commission.

“You act and serve as the conscience of our community,” he said. “May we always as a community be compassionate about the protection of human rights in Bowling Green.”

Edwards also recognized the work of Not In Our Town. Co-chairpersons Emily Dunipace and Dawn Shinew spoke of the organization’s efforts to stop hate, racism and bullying – and build a safe, welcoming community for all.

With the work just beginning this year, the Human Relations Commission has set the theme for 2020 as “Learning to Disagree Without Being Disagreeable.”

“We’re watching our country move away from Dr. King’s ideas,” said commission co-chair Jennifer Dever.

Dever said ideas are being sought on ways to cover this theme focused on living in harmony despite differences.

In conclusion, Edwards and his family were serenaded by Sheila Brown singing “Feeling Good.”