By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Wood County Common Pleas Judge Alan Mayberry uses a penny to show one of the flaws with State Issue 1.

He points to the minute beard on Abraham Lincoln, and explains it would take just 2 milligrams of fentanyl to cover Lincoln’s beard – and to potentially kill 10,000 people. Then the judge explains that under Issue 1, someone could be picked up with 19 grams of fentanyl and only be charged with a misdemeanor.

“That’s unconscionable,” Mayberry said.

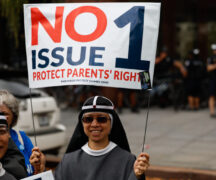

Wood County’s three common pleas judges are in agreement that Issue 1 – which will appear on the November ballot – would be bad for Ohio. The intent of the state issue is to offer treatment rather than jail time for drug offenses. The language makes the vast majority of drug offenses misdemeanors rather than felonies.

“The state is struggling with whether drug addiction is a crime or a mental health issue,” Judge Reeve Kelsey said.

But the judges – Matt Reger, Kelsey and Mayberry – said treatment is already being offered in Wood County. All that Issue 1 would do is result in the courts having one less tool to use to convince addicts to get clean.

“We see people in front of us every day,” Reger said. A simple slap on the hand is not enough to convince most of them to give up drugs – though in front of a judge they may profess their commitment to quit. “We’ve all had someone in our courtroom who has died a week later.”

Issue 1 would take away the judges’ “stick” and leave them only with the “carrot.”

“There’s no stick. There’s no consequence,” Mayberry said. “They can blow off treatment or restoration, and there’s nothing we can do to them.”

Wood County Common Pleas Courts already use graduated responses for drug offenders, with many people offered intervention in lieu of jail time, Reger said. Many of those sentences are designed with the individual in mind, he said.

The offenders can be ordered to attend treatment, get education, get mental health help, go to an anger management or domestic violence program, or perform community service.

“It’s giving them the tools to live,” Kelsey said.

“We already have gradual responses,” Reger said. “We’re already doing it.”

For example, Reger has required offenders to work on getting their GEDs, do volunteer reading to kids at the library, or work at the 577 Foundation.

“We try to be very individualized to that person,” he said.

However, if the offenders fail to follow through on the judges’ orders, the threat of jail is always hanging over their heads. That will no longer be the case if Issue 1 passes.

“All we can do is say, ‘No, no. Be a better person,’” Kelsey said. “This will not work.”

It’s not uncommon for an addict to come in for a drug test before arraignment, professing that they are drug free – only to be found with multiple drugs in their system.

“That person is not going to give up drugs,” voluntarily, Reger said. But under Issue 1, the judges would not be able to order jail time for a person who fails a drug test.

The three judges also feel strongly that making these changes in a state Constitutional amendment is improper.

“This is being put in the Constitution,” Mayberry said. “It cannot be changed if it isn’t working” – at least not without a great deal of effort. “Changing the Constitution is the wrong way to go.”

If changes are needed, they should be done at the legislative level – where revisions can be easily made if necessary, the judges agreed.

When Kelsey became judge, the biggest local drug problem was methamphetamines. Then it was opioids. Now it’s fentanyl. “Five years ago, none of us had heard about fentanyl. In five years, it will be something else,” he said. But a Constitutional amendment can’t be tweaked to deal with the latest issues, he added.

If adopted, Issue 1 would:

- Mandate that criminal offenses of obtaining, possessing, or using any drug such as fentanyl, heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, LSD, and other controlled substances cannot be classified as a felony, but only a misdemeanor.

- Prohibit jail time as a sentence for obtaining, possessing, or using such drugs until an individual’s third offense within 24 months.

- Allow an individual convicted of obtaining, possessing, or using any such drug prior to the effective date of the amendment to ask a court to reduce the conviction to a misdemeanor, regardless of whether the individual has completed the sentence.

- Require any available funding, based on projected savings, to be applied to state-administered rehabilitation programs and crime victim funds.

- Require a graduated series of responses, such as community service, drug treatment, or jail time, for minor, non-criminal probation violations.

- Require sentence reductions of incarcerated individuals, except individuals incarcerated for murder, rape, or child molestation, by up to 25 percent if the individual participates in rehabilitative, work, or educational programming.

The judges question the promise from Issue 1 supporters that the money saved by sending fewer people to prisons will be shifted to drug treatment programs.

“That’s pie in the sky,” Mayberry said.

They also doubt claims that Issue 1 will make “safe neighborhoods” in Ohio – with the focus being on imprisoning violent criminals and providing treatment to non-violent drug offenders.

“It’s going to be open season in Ohio for drug traffickers,” Mayberry said. “It’s going to be the wild west.”

Meanwhile, the change would shift a great burden onto municipal courts which handle misdemeanors. Those courts are not equipped for such caseloads, Reger said.

“It will overwhelm municipal courts,” Reger said.

Language in Issue 1 would also get rid of the “truth in sentencing” commitment in Ohio courts. The change would require reductions in jail sentences – for all crimes, not just drug offenses, Reger said.

The judges are not alone in their opposition to Issue 1. The state’s sheriffs association, county prosecutors, and Ohio Supreme Court have all voiced protests about the change. Mayberry said this is the first time all those entities have stood up against a statewide issue.

The issue does have its supporters, including criminal justice reform advocates, and agencies that operate addiction treatment programs – who see the change as a potential funding stream for treatment.