By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Many Ohioans are gambling with their health care.

They are people like Valerie who laughed when asked if her family got regular check-ups. They have to be “dying” to go to the hospital, she responded.

Keith rations his insulin.

And journalist Brian Alexander’s brother delayed going to the doctor for chest pains. He was waiting to be eligible for Medicare. He died before he could sign up. His brother found him 10 days later.

“We have underlying pathologies in our country that create physical pathologies in our people,” Alexander, a journalist who has written for Wired and Atlantic, told the members of the Words & Wine Book club and a few guests this week in Perrysburg. The club is sponsored by Gathering Volumes book store and meets in Cork & Knife.

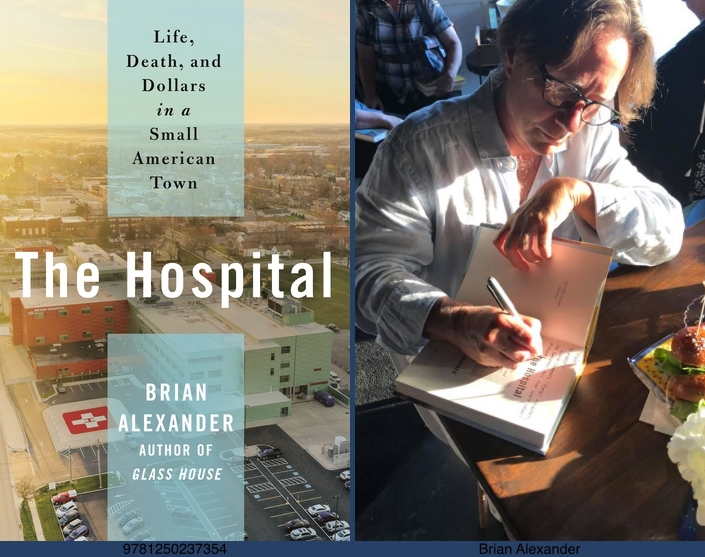

Alexander’s most recent book “The Hospital – Life, Death, and Dollars in a Small American Town” was the focus of discussion. U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur, D-OH9, attended.

“In Williams County and, unfortunately, other places around the state, many people are quite literally dying before they see a doctor,” Alexander said in an interview with BG Independent earlier in the day.

He grew up in Lancaster and knows first-hand the devastation suffered by small factory towns around the country in the last 40 years. His previous book was “Glass House: The 1% Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town.” In that book he touched on the problems of small community hospitals, which often are the largest employers in a place when manufacturing leaves. “A lot of them are in trouble.”

Phil Ennen, the CEO of Community Health and Medical Center in Bryan, called him and asked if he wanted a close up look at exactly how a community hospital keeps its doors open.

So Alexander, who lives in California, rented a house in Bryan and embedded himself in the hospital. It was a rare opportunity, he said, because hospitals usually don’t like having reporters hanging around. After Ennen left his job, Alexander was banned from the hospital for about a month before the board had a change of heart.

Ennen, he said, is rightfully proud of the hospital. It offers impressive oncology and radiation services. Still the locals refer to it as the “Band-Aid Station.”

Alexander learned early on that Bryan, a town of 8,500 or 10,000 if you include the outskirts, is bisected by its Main Street. “Working class and poorer people are on the east side,” he said. People on both sides die of cancer, but people on the east side of Bryan survive the disease eight fewer years than people on the west side.”

Demographically Bryan is basically an all-White town. The residents share the same gene pool. The only difference is whether they live in the wealthier or poorer census tract.

That’s true elsewhere. In the Franklinton neighborhood in Columbus the life expectancy is 69. In Stow, it is 85. “It has to do with poverty, education, access to good food and affordability of good food,” Alexander said. “The way we have set up our country over the last 40 years is bad for people’s health.”

That includes the replacement of good, often union, jobs, with benefits and good income with poorly paid, often part-time, service sector jobs with few if any benefits.

People are already struggling to get by, he said, “then they get sick, and they’re forced to encounter this whole other parallel track which is the medical economy, and they have no idea how to do it.”

The health care sector is the largest in the U.S. economy, about 19 percent. “Our health care system grew by accident,” he said. “Nobody designed it.” It grew because people in industry figured out how to extract a lot of cash by exploiting the system’s nooks and crannies.

It’s now approaching $4 trillion and “Americans life expectancy is declining.”

Community hospitals are caught in the middle.

“They exist within this crazy jigsaw puzzle of health care in America,” he said. “They have to play the health care game to keep their doors open. They try to do that and they tell themselves it’s because they want to serve the people of Bryan. But if you’re going to do that in the United States, you have to turn medical care into a business.”

They face being taken over large systems – Pro Medica in Toledo and Parkview in Fort Wayne.

As part of his research, Alexander read many studies on health care consolidation. “When hospitals consolidate prices rise and the quality of care stays the same or declines,” he said. “The argument these big systems use is we can offer all these great services and quality goes up. That’s not true.”

His stay in Bryan lasted about a year and a half, right before the pandemic. The pandemic extended his research – he did additional telephone interviews to check on how Bryan was faring with COVID-19.

Not well, he said. “The interesting thing about the pandemic is it confirms all the reporting I had done before. …. The pandemic just blew them all open … the fractures and fault lines not only in health care but in American society.”

The county had just over 3,500 cases and 78 deaths with a population just shy of 37,000. Only 34 percent of the eligible population are fully vaccinated and only about half the hospital staff is fully vaccinated. This is not surprising, he said, given 75 percent of the county’s electorate voted for Trump.

Asked what he thought the solution would be, Alexander prefaced his answer saying: “I am not a health policy expert, I’m just a reporter.”

Still, he continued: “I went into the book being somewhat skeptical with the solution being national health care. I am no longer skeptical that the solution is national health care. We need some sort of national health care plan.”

Globally many variations of national health care systems exist. “They all work better than what we have. We pay three times the amount of money, and we have worse outcomes than any of our peer countries, and they have national health care plans.”

Plenty of debate is possible over the details of such a plan, but that a family can lose its medical coverage, or the cost can skyrocket, because someone loses or changes jobs, is “ridiculous.”

The fears about the long waiting times and delays in service are “a myth,” Alexander said. “We have rationing, we just don’t call it rationing.”