By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

He called her Mama.

She called him Buddy.

He was the guy who got up first to fix breakfast for the rest of the guys he shared a house with.

“I’ll tell you very proudly,” Lavin Schwan said during a presentation on campus Wednesday, “that was the son that I raised. That was Joey’s heart. That was the Joey I remember.”

Then she added: “But the drugs took that.”

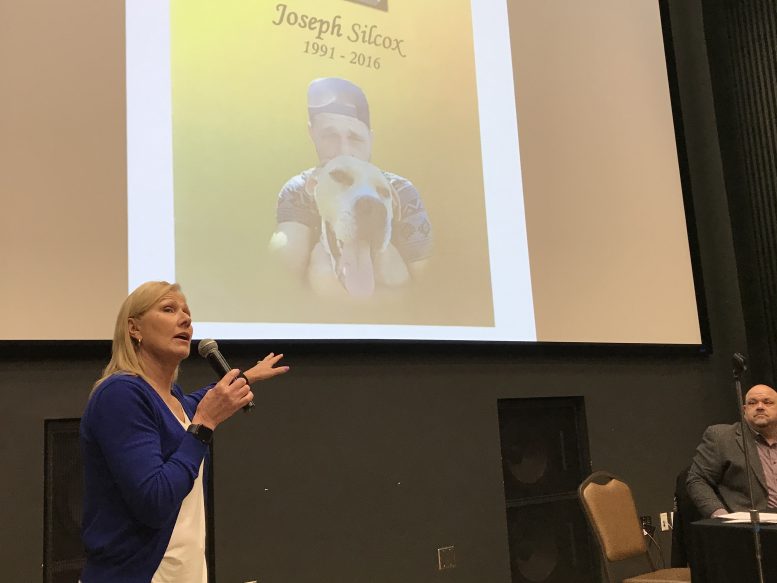

Schwan and her husband, Tom, were at Bowling Green State University to share “Joey’s Story: A Family’s Personal Journey with Opioid Addiction.”

Joey Silcox, a former BGSU student, was her son, and Tom Schwan’s stepson.

Those guys he made breakfast for were his fellow patients in a rehab facility in California.

One of them, Kevin, shared details of Joey’s time there. Kevin said he arrived a week after Joey, and couldn’t sleep, so Joey settled in at the end of the bed to let him know he was not alone.

Joey had finally gone to rehab after the scope of his problem had become apparent when he was caught on video stealing tip money from fellow workers at the restaurant his family owned.

Tom Schwan admitted they were naive about the problem. They had not understood the signs — the absences from work, the constant cadging for cash.

So when after two months away, Joey arrived back home from rehab, and they thought he was fixed.

Two days later, his sister found him dead in his apartment. His beloved dog Brooklyn, watchful at his side. Joey was 25.

The signs of his problems had been evident though long before, even before he was born.

Schwan said addiction runs in her family. All three of her younger brothers struggled with it as did their father. Her brothers are now sober and in recovery, Schwan said. Their father, an alcoholic, ended up committing suicide. “That is how he escaped his disease of addiction,” she said.

“Joey was born into a family with a strong genetic link to the disease of addiction,” she said.

At 13, she discovered he had started smoking. “I was devastated by that.”

Joey was a stellar student and an athlete who played multiple sports. She warned him of the dangers of addiction. Smoking was the start down that road.

But he assured her he could quit any time. He said he enjoyed how the nicotine made him feel. It helped him relax.

He graduated from Old Fort in 2009 and headed to BGSU to study business.

About six months later, Schwan received a call in the early morning hours from him. Campus police had pulled him over while he was out with friends, and they found drug paraphernalia. He wanted his mother to bail him out.

She refused, hoping the experience of being in jail would serve as a lesson. Joey’s girlfriend did bail him out. But he couldn’t keep clean. His random drug test came back positive for Adderall, a drug used to treat attention deficit disorder that was also misused as a stimulant.

When he got his wisdom teeth pulled, his first concern was what they would give him for pain. “I don’t know, Buddy,” his mother told him. “We’ll see when we check out.” He got a 30-day prescription for Percocet.

While at BGSU he lived with a group of guys. They liked to party — drinking and probably smoking marijuana. “It was a college thing. He’ll outgrow it,” his mother thought.

He left BGSU to work at a roofing company owned by a college friend’s family.

For a time, he went to work with his uncles’ home improvement business in Michigan. That’s when he was discovered snorting drugs in a company truck. He was given a second chance.

All the addict cares about, Lavin Schwan said, was keeping from getting dopesick. The sickness that comes when they don’t take drugs. So they would break into cars and take change and steal from loved ones.

Joey ended up coming to work for his family’s restaurant. A customer spotted him on the floor in the rest room. He’d been snorting cocaine, he admitted to his stepfather. His stepfather agreed not to tell his mother if he got counseling. But Joey quit going to his appointments.

Then he was caught stealing.

When his mother found out she was sick. She confronted him: “Buddy, you need to go to rehab.”

But she didn’t even know how to arrange that. She saw a billboard at the side of the road offering help. She scribbled the phone number down and called. She made arrangements. All she knew was that the cost would be covered by her insurance which Joey under, and that they had a bed.

A few days later, after a family meeting, Joey flew to California to spend what would be the last two months of his life.

In the wake of his death his family has used Joey’s story to help educate people about the dangers of what has become a drug crisis more than an opioid crisis.

Tom Schwan noted opioid and heroin deaths are down because some people are scared off. But methamphetamine use is up.

They share Joey’s Story, and have started Bellevue Recovery and Support Services, which offers referrals and information for families like theirs as well as hosting support groups.

They hope that through their efforts people will come to understand at least one small part of the problem, and then share what they’ve learned with those they know, whether a prayer group or bowling team.

“We’ll continue to share this story as long as doors are open to us, so people understand addiction is a disease of the brain,”Lavin Schwan said. “It totally hijacks the brain and short circuits the circuitry of the brain, and they lose control.

“Joey never thought he’d lose control,” she said. “Joey never thought he’d die at 25. Neither did I.”