By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Some political scientists thought that Donald Trump may signal an end to the polarization that has been widening since the 1970s.

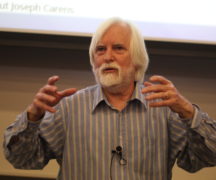

After all, Trump was hardly the typical Republican, noted author Nolan M. McCarty during a recent talk at Bowling Green State University.

Trump’s positions on trade, massive investment in infrastructure, and, to a large extent, immigration were not the kind of positions that the hypothetical mainstream Republican “Jeb Rubio” would support, McCarty said. Trump promised to preserve Social Security and Medicare in their current form, and possibly expand them. He was the first president who supported gay marriage from the beginning of his presidency. Trump had also been “promiscuous” in terms of party affiliation — he’d been a Democrat, Republican, Reform Part candidate, before finally settling in with the GOP.

“Trump might have made things better,” McCarty said, if he’d reached out across the partisan divide to seek Democratic support on those issues. “But he really didn’t.”

Instead he chose a “very partisan strategy” that alienated those who might have worked with him.

And his legislative achievements, such as the tax bill, have been the same as those that a “Jeb Rubio” administration would have sought. Trump’s push to build a border wall being the exception.

McCarty, a Princeton professor, is the guy who wrote the book on political polarization. He came to campus under the auspices of the Philosophy, Politics, Economics and Law Program to speak on his book “Polarization in America: What Everyone Needs to Know.”

He said that what many think they know about polarization is not proven out by the data.

First, he said, polarization is not necessarily bad. The Goldilocks effect where a middle ground majoritarian view holds sway squeezes those on the edge, left or right, out. Diversity of voices is good.

Looking at congressional roll call votes as a measure, McCarty said, that signature events such as the election of Ronald Reagan, or Bill Clinton, or the “hung election” of 2000 did not lead to greater polarization.

Nor does gerrymandering increase polarization.

And, the common view, that both parties are involved is also not the case.

Conservatives have been much more successful in pushing the Republican Party to the right than progressives have been in pulling their party to the left.

Also, the electorate is not driving the division. Rather it is the office holders and political activists who are opening the divide.

The more politically active and knowledgeable someone is, the more likely they are to hold extreme views, one way or the other, McCarty said.

There are still districts that spilt their votes between the presidential candidate of one party and the congressional candidate of another.

The voters, McCarty said, are reacting to “polarized choices.”

And, he said, changing our system of primaries may be worth considering but the evidence from California and Australia where this has been tried indicate this would hardly be a panacea.

Nor would be bringing more disaffected “moderate” voters back into the process. It’s likely, he said, they would only get active if someone pulled them in with more extreme views.

“The average view of voters among political scientists is they’re reasonable people, busy people. They’re engaged in lots of things, but not in politics,” McCarty said. “So they have to learn a lot about politics by watching the media, watching members of Congress, listening to what the president said. It’s not that voters have decided on their own to become more polarized.”

Rather it is politicians making appeals that force them away from the middle.

McCarty pointed the finger at the way campaigns are funded as a far greater problem. The United States is distinctive among democracies in relying on private funding of political campaigns.

It’s not that corporations are tilting the field. “Corporations tend to be fairly moderate and pragmatic,” he said.

It’s individual donors who contribute most to candidates on the edges, that includes those who give modest amounts to Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, as well as wealthy individuals.

The greatest change in financing has been the dominance of the very wealthiest donors. In 1980 the top tenth of the top 1 percent made 15 percent of all contributions to candidates. “An obscene amount,” McCarty said. Now that figure is as high as 40 percent.

This points to “a striking correlation” between increased polarization and income inequality.

Polarization has led to gridlock, and to the extent that conservatives favor less government action, it would seem to favor them, though it also blocks actions they would like to take.

This does provide a regulatory stability. However the world, McCarty noted, does change, and this gridlock cripples the government’s ability to address issues such as climate change, income inequality, and immigration.

The country, he said, has not always been so divided. It was in 1877, right after “a bloody Civil War,” when each side looked at the other as traitors. But that eased. By the earlier decades of the 20th century there was little difference between the two political parties.

That started to change in the 1970s. Now the country is as polarized as it was following the Civil War.

People who say they would be disappointed if their child married someone of the opposite political party stands at 35 percent — that’s similar to the level of disapproval expressed about interracial marriage in the 1960s. “There’s some evidence people are starting to think party identity as an important social identity.”

When writing “Polarization in America,” he put off drafting the last chapter that would deal with the Trump presidency. Finally, with his deadline at hand, he wrote something optimistic about how Americans could be assured the Constitutional system of checks and balance would hold. He submitted it, and then Jeff Sessions was fired. He considered rewriting that, but decided that the optimism was still warranted.

He is concerned when watching the Democratic debates that all the candidates promise to act in a Trump-like manner. They announce what they’ll propose on their first day in office, and if Congress doesn’t go along, they’ll do it by executive action.

Such a process that makes a runaround of the legislative and judicial branches, he said, may be a legacy of the current administration, and “it will be hard to extinguish.”