By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The praise for the writer’s fiction came from all corners.

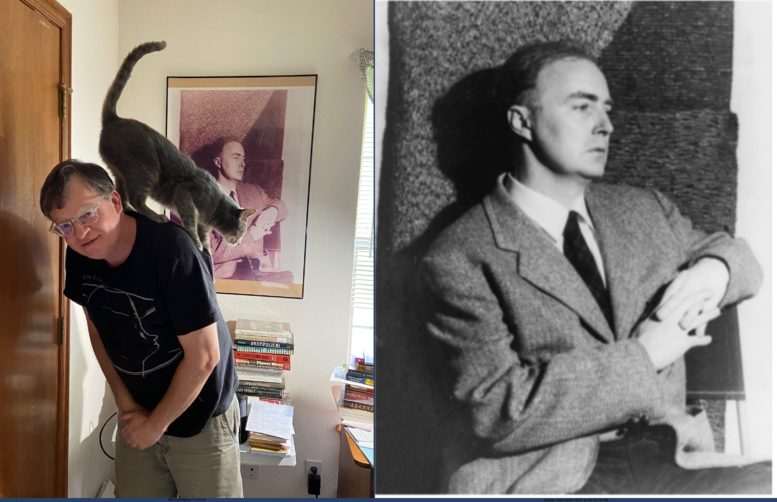

Langston Hughes, Tennessee Williams ,Dorothy Parker, Susan Sontag, Jonathan Franzen and other luminaires were fans – a literal who’s who of literature. Yet the subject of this admiration, James Purdy, even from the well-read public, is likely to elicit the question: “Who’s that?”

Maybe the reason is spelled out in the title of Michael Snyder’s just published biography “James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian Writer” on Oxford University Press.

Purdy who died at age 94 in 2009 published beginning in the late 1950s 15 novels as well as poems, short stories, and plays. He published his last story shortly before he died.

Purdy, who was born in Hicksville and grew up in Findlay, told Snyder in one of their telephone interviews near the end of his life that he considered his creative work to be his biography. That’s never more true than in his novel “The Nephew” set in the fictional community of Rainbow Center, modeled closely Bowling Green. The characters are avid readers of the local newspaper, The Sentinel.

The characters are modeled on his own family and neighbors in the four years, from 1932 to 1936, he spent at 135 Ridge St. in Bowling Green while attending Bowling Green State University. He earned two bachelor’s degrees, one in English with a history minor and the second in Education with an English and a French minor. After graduation he never returned.

But he remains of interest to a few BGSU scholars.

David Kuebeck is a member of the James Purdy Society and has done research on the writer’s time in BG. “He’s done amazing research and has been very generous,” Snyder said. Kuebeck’s scholarship added greatly to the sections related to Bowling Green.

Snyder is interested in seeing what else Kuebeck uncovers. “There’s more to be said.”

According to Snyder’s biography, in 1971 Purdy told another local researcher BGSU professor Frank Baldanza: “I hope you won’t dwell on my biography. My only biography is in my books. I never fitted in in Ohio any more than here. I was always a kind of outcast. I have no really friendly feelings toward that community.”

When “The Nephew” was published in 1961, the feelings were in many ways mutual. The book riled his former neighbors on its publication, but it sold well in Bowling Green, Snyder said.

Some the campus community suspected that one professor took his own life nine months after the book was published because it revived an old scandal involving the man having sex with a female student. Snyder said he can imagine why the professor was “embarrassed” by his portrayal and hurt. Purdy had taken two year-long courses with him and was a neighbor.

In Bowling Green, Purdy lived with his Aunt Cora, father William Purdy, and grandmother, Kitty, who died shortly after he moved in.

His parents had divorced when he was 15 and his mother, Vera, ran a boarding house for traveling salesmen in Findlay where Purdy grew up. Her occupation and the rumors about her relations with some of the boarders did cause embarrassment.

“He was a person who was haunted by his family,” Snyder said

Even before his parents divorced, his father, who was in real estate, was often away on business.

In “The Nephew” the character modeled on Purdy is absent. Through the course of the book we learn that the nephew Cliff has died while serving in the Army in Korea. His Aunt Alma sets about writing a memorial for him, but finds she knows nothing about this young man to whom she was so devoted. She goes around the neighborhood seeking what little information she can find, some of it disconcerting.

Purdy didn’t fit in with the Bowling Green community nor on campus. He preferred hanging out at a local Greek restaurant.

Purdy was openly gay, and later in life when asked when he came out as gay, he replied he always was out.

His blunt portrayal of gay characters was probably a factor in why he failed to latch onto a large audience. In the Cold War period, he was viewed as “effete,” Snyder said.

While it has its quirky characters and an undertone of the bizarre, “The Nephew” is one of his most conventional novels.

Others such as “63: Dream Palace” and “Narrow Rooms” are edgy with candid discussions of sex and lurid descriptions of violence. Yet even in what seem like the least autobiographical works, Snyder sees reflections of Purdy’s life.

“Eustace Chisholm and the Works,” considered his most popular work, includes a vivid description of an illegal abortion in depression-era Chicago. Purdy had brought a friend to have an abortion during his time in Chicago.

The book prompted a withering homophobic review by critic Wilfred Sheed, Snyder said. Purdy was disappointed his publisher Roger Straus refused to stand up for the book. The publisher, Snyder said, may not have read the manuscript to the end and didn’t realize the dark turn it took and was embarrassed his firm published it.

Purdy was not a propogandist for gays, Snyder said. “He was a true literary artist of integrity. He wrote about what he experienced, but he was reflecting things, refracting things the way great writers do.”

After graduating from BGSU he went to University of Chicago for graduate studies, and then enlisted in the Army Air Corps and then taught for a year in Havana.

His years in Chicago were formulative. There he became part of the circle of the artist Gertrude Abercrombie which included jazz greats including Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie as well as visual artists and literary figures. He eventually taught for many years at Lawrence University in Appleton.

He left in 1956 to follow his lover Jorma Sjoblom, who’d taught chemistry at Lawrence. Sjoblom had taken a job in industry in Pennsylvania.

It was at this time, that Purdy started finding success in publishing his works.

Though he had some popularity he never had a best seller, Snyder noted. The only film adaptation of “In a Shallow Grave,” based in part on a notorious murder in Findlay, was not successful. The filmmakers “straight-washed” the story downplaying the same sex relationship, Snyder said. Purdy did sell the movie rights to “Eustace Chisholm” to Hollywood, a financial boost for Purdy. Otherwise he lived on grants and awards, money from benefactors, and the occasional teaching job.

Purdy and Sjoblom eventually moved to New York City. Purdy spent the rest of his life there.

He had, Snyder said, a streak of self-destruction. He was at war with the New York publishing establishment. Some said he was his own worst enemy.

And he avoided any sort of probing into his past. The biography tells how even Sjoblom didn’t know for a long period how old Purdy was.

One scholar showed up at his door in New York, and Purdy hollered down as the unexpected visitor waited in street that Purdy doesn’t live here anymore.

His biographer Snyder who grew up in Ohio found himself drawn to Midwestern writers. He was researching the writer James Leo Herlihy, who wrote “Midnight Cowboy” and “All Fall Down,” when another scholar suggested he check out Purdy.

Snyder had some familiarity with Purdy’s books. The dark imagery and the way he used indigenous imagery as a way of interrogating the American experience attracted Snyder. Purdy was proud that he had a great-grandmother with a strain of Anishinaabe lineage. Purdy was praised for his concerns for those marginalized by society including indigenous people, Black Americans, and members of the LBGT+ community, though he didn’t shy away from using the most derogatory terms.

When Snyder completed his dissertation in 2009, Purdy was the subject.

He did get to interview the author by telephone three times. They were good conversations, Snyder said, but Purdy “did not like it if I asked for specifics, if I asked deep questions, about Findlay or Bowling Green.” He did not want to delve into the people who were models for his characters.

Now that he’s gone, Snyder doesn’t think he would mind having a biography published, especially if it draws new attention to his work.

“He rated himself highly,” the biographer said “He knew he was a great writer and he was not shy about wanting recognition of his talent. I like to fancy he wouldn’t mind at this point.”