By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Migrants searching for a better life in the United States, a life free from violence and poverty, sometimes find a lonely death in the wastelands along the border.

Jody Ipsen (left) and Peggy Hazard

The Tucson Sector is the most deadly. And just as American economic and political policies have left many in Central America with little recourse but to flee, so American border policies have funneled them into the most deadly terrain. Since the late 1990s, an average of 150 migrants a year died in the area.

Jody Ipsen, a quilter and writer, was backpacking in the area when she came upon what had been a camp for migrants. They’d left behind clothes and embroidered towels that are used to wrap tortillas. She found these traces of their passage through the area touching. That inspired the Migrant Quilt Project.

Ipsen and curator and quilter Peggy Hazard visited Bowling Green State University this week as part of the annual Immigrant Ohio seminar.

Ipsen and curator and quilter Peggy Hazard visited Bowling Green State University this week as part of the annual Immigrant Ohio seminar.

The quilts that have been produced by the project are on display through Dec. 7 on the fourth and fifth floors of Jerome Library on campus.

Ipsen collects what the migrants throw away and then with the help of quilters, creates memorials to those who have died.

Ipsen said she never uses material from a site where someone has died out of respect and so as not to interfere with the medical examination of the site.

Rebecca Mancuso looks at quilts displayed before talk in student union.

As barriers have been put in place at the locations that are easier to cross, migrants have shifted into the harsher areas. This is part of US policy, she said. Officials say they hope the difficulty will deter migrants. That has not been the case. Thousands have died. “Death by deterrence,” Ipsen called it.

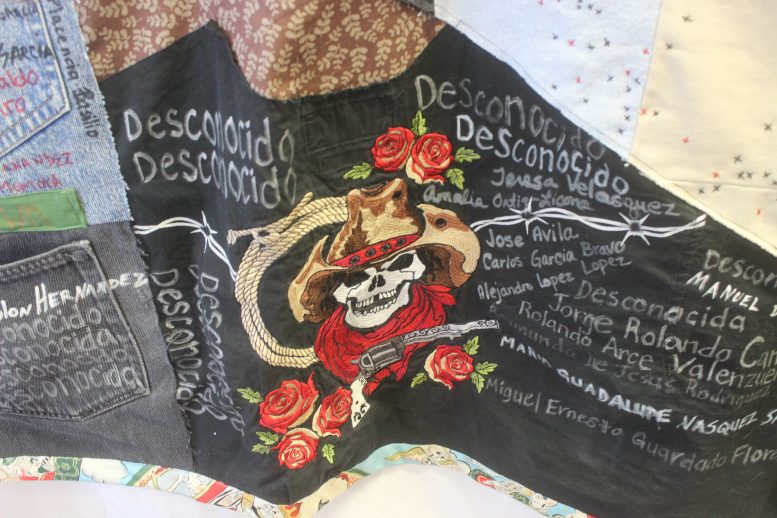

The quilts serve as a reminder of their deaths, she said. Each quilt has an inscription for each person who has died, whether the person’s name or simply as unknown, or “desconocido,” for the many whose remains have not been identified.

This is a reminder, Ipsen said, that these were people with families and friends.

Ipsen told the story of three women whose stories she researched.

Jody Ipsen gives a tour of quilt exhibit in Jerome Library to a group of local artisans and library staff.

Prudencia Martin Gomez headed north to find her boyfriend Ismael. He’d had to flee Guatemala because of lingering resentment over his father’s involvement in Army atrocities during the country’s 30-year-long civil war.

Prudencia was hoping to surprise him on his birthday. “She never made it,” Ipsen said. She showed an image of Prudencia’s body as it was found in the desert. While warning the audience of graphic nature, she said people also needed to see the reality of the crisis.

Ipsen choked up. She had talked to the families and came to know these women and what their loss meant to their survivors. “It’s really painful for me to talk about.”

Yolanda Garcia Gonzalez left with her 18-month-old daughter when the local agricultural economy collapsed following the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994.

The agreement allowed a flood of cheap American corn, rice and beans into the country. Small subsistence farmers, Ipsen said, could not compete. Their centuries-old farm system collapsed in a matter of months.

The agreement allowed a flood of cheap American corn, rice and beans into the country. Small subsistence farmers, Ipsen said, could not compete. Their centuries-old farm system collapsed in a matter of months.

“It’s no wonder people are coming to the country that is unequivocally responsible for dismantling their small scale economies,” Ipsen said.

Migration and death along the borders skyrocketed over this time.

So Yolanda headed north to meet her husband who was working in Texas. She did not make it. She gave her last few ounces of water to her daughter, who was found alive, and now lives with her grandmother.

Lucrecia Dominguez also came to rejoin her husband. She ended up dying in her 15-year-old son’s arms. He went to find help and was arrested. He needed to find his mother, he told the border patrol. Instead the agents brought him to Nogales, Arizona and returned the boy to Mexico. The son contacted his grandfather, who had a visa, and returned to the area to search for his daughter’s remains for three weeks, guided only by his grandson’s memories. He came upon three other skeletons before finding his daughter. He was only able to identify her by the three rings on her finger.

Fabric Artist Susan Krueger studies a quilt hanging on the fifth floor of Jerome Library.

Peggy Hazard, a curator and fabric artist, said she became involved in the project when another quilter Suzanne Hesh asked her to help complete the second quilt.

The first was made in 2008 by a Tucson social service agency that assists low-income Spanish speaking people by the families and the staff. The imagery on the quilt looks festive at first until the viewer studies the detail.

The quilters are provided with the materials collected at the site. Jeans are the most prevalent, as well as hats and other articles of clothing. Hazard said she finds the embroidered clothes the most heart-wrenching. Someone embroidered these and now they were left behind as trash. And, she said, it’s easy to think that at the beginning of the migrants’ journey warm tortillas were wrapped in the clothes. They are provided a list of the deceased.

The quilters can design the work anyway they wish with a few parameters, Hazard said.

The designation Tucson Sector must be on the quilt as well as the date range, the federal fiscal year, represented. And then the name or unknown for each of the dead.

The quilters must provide the foundation fabric and all other materials.

The approaches vary greatly. Hazard said she incorporates images of our Lady of Guadalupe in many.

Another quilt maker had a landscape of the desert across the middle. It seems like an inviting image, maybe something from a tourist brochure, but what it depicts is a landscape of death. Another sewed on tiny crucifixes and charms. Another chose to leave edges ragged.

On the bottom corner of one, the quilter draped an embroidered cloth. Under that cloth she’s written a message to a deceased migrant: “Did you see a bird the day you died? Were you hot, thirsty, and frightened?”

Hazard said the project was inspired in art by the AIDS quilt of the 1980s, which helped people to see the human dimension and toll of the disease. But social justice quilts have been created dating back to the Abolitionist movement in the mid-19th century.

Hazard showed images of quilts that are now being made by the migrants themselves. These depict their own harrowing experiences.

“We are sympathetic outsiders,” Hazard said of those who make the migrant quits. “For us this is a human rights cause.”

While immigration is widely debated, she said. “what’s lost is the human, the personal side, of the story. We hope that this will make a difference, and by doing this we’ll contribute to the conversation.”