By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Tom Bridgeman, director of the Lake Erie Center at the University of Toledo, knows what will happen when people read the news stories about the harmful algal bloom forecast for western Lake Erie.

They’ll rush out to a big box store and stock up on bottled water. He has different water-related advice: “Go jump in the lake.”

Lake Erie is beautiful now, he said. The algal bloom hasn’t set in yet, and won’t for a couple weeks, and when it does it’ll last for just a month or so, probably peaking in September. People concerned should monitor the shorter term forecasts.

Bridgeman was taking part in a panel of researchers following the announcement of the harmful algal bloom forecast for western basin of Lake Erie.

The forecast announced Thursday at a press event at the Aquatic Visitor Center on South Bass Island looks for the bloom to be at 7.5 severity in the open ended scale. Richard Stumpf, an oceanographer from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who presented the forecast, said he was 85 percent certain that the severity would fall within the 6-9 range. The most severe bloom was back in 2015 was a 10.5 — scientists set the scale at 10 in 2011 because they thought that’s as bad as it could get. Last year was 3.6 and 2017 was 8.

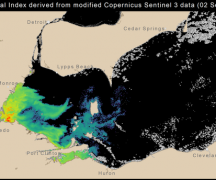

The forecast addresses only the size of biomass of the bloom. It can’t pinpoint where it’ll be — that depends on winds, though the Ohio shore tends to be where it accumulates.

Nor can it predict if that algae will become toxic.

Researchers, including several at the event, are at work trying to find a way to forecast that so the area would not be taken off guard as it was in 2014 when a toxic bloom settled right off the intake pipes of the Toledo water distribution plant leaving about 500,000 people in the region without water.

The algae growth is caused by the flushing of nutrients, particularly phosphorus into the Maumee Watershed. Those can come from a variety of sources, including waste water treatment plants, landscaping, and agriculture.

Because of the very wet fall and spring, though, agriculture has been disrupted.

Yvonne Lesicko, of the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation, said that in the northern Lake Erie Watershed, about a third of the farmland has not been planted because of flooded fields.

In spring, farmers applied far less manure and commercial fertilizer to their fields. She said farmers used 15 percent of manure as normal and 50 percent of commercial fertilizer.

That appeared to show up in the water samples collected by researchers from Heidelberg College.

Laura Johnson, director of the project, said that 454 metric tons of bioavailable phosphorus went into the lake.

That’s neither the lowest nor the highest number from the last 10 years. But, she said, that’s less, by about 30 percent, than she would expect based on the amount of water that flowed into the Maumee because of the heavy rains.

Stumpf said that if the phosphorus load had been higher, the algae bloom would have been “significantly” larger.

Many farmers were unable apply fertilizer in either fall or spring. Those applications that sit on the top two inches of the soil are the most susceptible to washing away, Johnson said.

Agricultural practice, though, is to build up a “bank” of phosphorus in the soil to nourish crops in years when they are unable to apply fertilizer.

Stumpf said that last year’s forecast was off. A forecast of a 6 turned into an actual measure of 3.6 in severity.

Last year was unusual in many ways. The lake heated up early so the bloom started in late June, a month sooner than normal, and then it dissipated earlier in September, in part because of unusually high winds.

Stumpf said NOAA has fine-tuned the models it uses to make the forecast.

The research that’s been conducted in the past decade has “increased our understanding significantly,” said Tim Davis, of Bowling Green State University. The funding provided by state and federal governments and support from academic institutions has led to new ways to study and address the problem.

“We’ve made progress in a lot of areas,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we know everything we need to know.”

Justin Chaffin, a senior researcher at Stone Lab, said that he’s involved in looking more at nitrogen’s role in turning those algae blooms toxic.

Phosphorus has been studied more because it is the “key driver” of algae blooms, Stumpf said.

Chaffin said that a correlation between higher levels of nitrogen in the lake and a higher level of toxicity has been noticed. That link has to be studied more.

Johnson said progress has been made in the determination of “best practices” for agriculture and their implementation of those throughout the basin.

The results this year indicate that a change in conditions can have a dramatic effect.

“We probably take for granted that Ohio is really on the cutting edge of this issue,” said John Bratton, a geologist with Limno Tech.

People studying similar issues from California to Florida to Lake Champlain between Vermont and New York, are looking to Ohio for guidance. “The problems are not solved yet. We don’t have the system where we want it to be, but we’re much further along.”