By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The creation of art both reflects a sense of hope and gives the viewer a sense of hope, said Charles Kanwischer, the director of the BGSU School of Art. Kanwischer was reflecting on the work in 2022 Master of Fine Arts exhibit.

The art created by the eight graduates in the program goes against “the tide of coarseness and generalities,” he said at Friday’s opening ceremony for the show. “What I see in this exhibition is an emerging lifelong commitment to finding and sharing the particularity of individual existence. That’s what our society needs now, and what it will always need.”

The artists featured are: Benjamin Rosales, Michaela Westra, Mike Rutkowski, Isabel Zeng, Audrey Aronson, Kolton Lucius Sizer, Crystalyn Hutchens, and Amanda Spinosa

The exhibit in the Bryan Gallery in the Fine Arts Building continues through April 30. Gallery hours are Tuesday – Saturday 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., Thursday evening, 6-9 p.m., and Sunday, 1- 4 p.m. (Closed today, April 17).

While bound by a shared commitment to craftsmanship, the inspiration for the work comes from a variety of sources.

Hutchens’ large scale graphite drawings and paintings draw inspiration from her diagnosis of a chronic illness. That illness takes its toll, but is not necessarily visible to the observer. The nude figures fill the frames, seemingly wanting to break out. Rendered in gray tones, they’re sculptural, at once stone-like and yet fluid, always struggling.

“Two Inhabitants,” the title of her exhibit, reflects the tension between what her body wants to do and can do. She’s drawn inspiration, not just from her own life, but also from others who suffer from disabilities. “In this series of work,” she writes in her artist statement, “I create a visual language for communicating the physical and mental experience of individuals with chronic illness and invisible disabilities from a female perspective.”

[RELATED: Emerging artist takes best of show honors at NowOH]

Sizer’s “Straw Dog,” a collection of charcoal drawings, was also inspired by a health crisis.

A year ago, he said, he was hit by a car while he was walking. His concussion was so severe, his doctors told him he couldn’t watch anything with colors. “They didn’t want all those neurons firing,” he said.

Sizer fell in love with film noir movies, and he drew inspiration from them, especially those moments just before the “inciting incidents” from which the plot unfolds.

He set up the scenes he envisioned, photographed them, and then used those images as the models for his large charcoal drawings.

For Spinosa, it was the death of her grandmother that sparked the work included in “Unpacked.” The series features images that are a hybrid of printing, collage, and drawing.

“These pieces come from a sentimental place,” she said.

When her grandmother died, Spinosa received her clothing. “I created a special bond with them. I wanted to remember them and experience them in a new way.”

The images each feature an individual item of clothing. The item could have just been taken off, or it could be set out waiting to be put on.

Westra’s encaustic paintings are also about memory. She selected the medium because it is one of the most long-lasting. Encaustic paintings can last thousands of years.

“I use it to preserve personal history, knowing it will last longer than I am around. ”Westra, who grew up in Michigan, depicts family memories that are often forgotten, small but evocative moments. The settings are both rural and domestic with a sense that the people involved have just stepped out of the frame.

“This was a completely new journey for me,” Rutkowski said. He was doing digital 3D rendering of still images. But he was drawn to video game design. He found himself thinking about “the connectivity between the viewer and the creator,” he said. “It was the temptation to do something new on video games. I think it was the interactivity of it.”

The result is “The Space Between,” which takes the viewer on a journey into the world that an artist has left unfinished. “Along the way they’ll discover what hides in the back of an artist’s mind,” Rutkowski writes on the postcard promoting the game.

Aronson’s vision also evolved in her time at BGSU. “When I got here I was really interested in feminist theory which is still a passion.” But, “my work shifted to be more personal and introspective since I got here. … It addresses issues of vulnerability and self-protection.”

Since high school she always knew she wanted to work with her hands, but creatively, instead of a traditional trade.

“Jewelry was a perfect fit,” she said. “With all the processes and the wide array of materials you can use, it’s a very open field and free.”

That BGSU was a two-year, instead of a three-year, program was also an attraction. “I thought the intensity would be good for me,” she said.

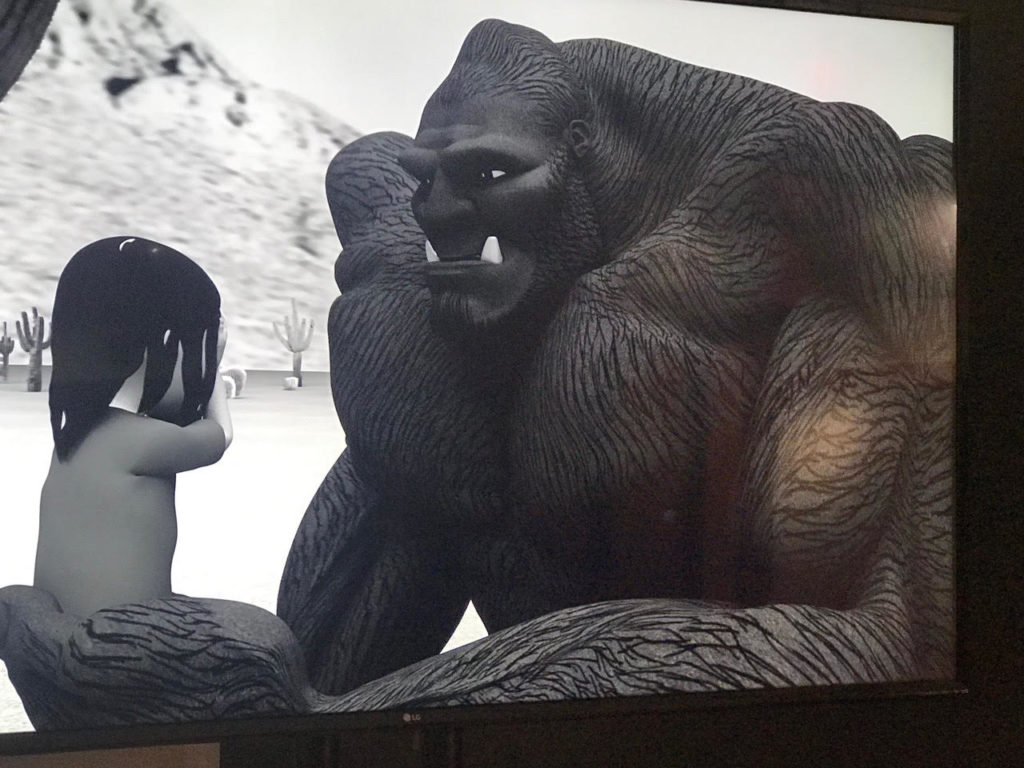

Rosales came to BGSU with a vision in mind. It took him five years as a part-time MFA student to create the first episode in what he hopes is a series about He-Who, a Sasquatch creature. “In every episode he is going to transform a symbol of hatred and intolerance into a symbol of love and acceptance and do his best to save people who are suffering from social injustice around the world.”

The film is digitally animated with hand-drawn dream sequences.

“The story was inspired by what I saw on the news, I think it was 2017, 2018,” Rosales recalls. “I saw a mother running for her life with her two children from the border trying to keep her children safe from tear gas. That made me so angry that I had to do something. I decided to build a story around that.”

Rosales, who has taught in community colleges around the Midwest, said he found in BGSU a place that allowed him to realize his vision.

Zeng also took five years of part-time work to complete her MFA. When she’s not in the studio, she teaches economics as an associate professor in the Schmidthorst College of Business across campus.

Her exploration of art, she explained, started with a few courses at the Toledo Museum of Art, then she looked at how she extend that work at BGSU.

As a metalsmith she wanted to work with Tom Muir. Her vision evolved. She’d always been interested in performance, but the School of Art does not offer courses in performance art.

Still, she incorporated it into her art practice.

“My heart changed,” Zeng said. “Still I identify as a craftsperson. I still make objects, then I perform wearing the objects.”

Zeng said she’s proposed teaching a course in the school in performance and media.

Her sprawling MFA exhibit that extends into the Red Door Gallery adjacent to the Bryan Gallery includes three screens showing her performances as well as a display of metalwork that she created.

She’s uncertain of the connection between her art work and economics. There’s no implicit connection, she said, other than herself. “It’s just a way of thinking. I think like a social scientist, and in the meantime I kind of apply that in my art practice. It’s odd. I like doing both.”