By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

“Wow!”

That was the assessment of one attendee at the press preview Friday for “Marisol: A Retrospective” at the Toledo Museum of Art.

That reaction came not from one of the assembled reporters listening intently to curator Jessica Hong’s commentary on the late artist’s work. It came from a toddler who accompanied his mom and her camera gear to the preview.

“Wow! That’s big,” he reiterated.

Marisol – born of globetrotting Venezuelan parents in Paris in 1930 – has gotten that kind of reaction since she emerged on the New York art scene in the mid-1950s. People lined up around the block to visit her gallery shows.

It was a reaction both to her art with its elements of folk and pre-Colombian art seen through a distinctly cosmopolitan lens and her person. Marisol Escobar was a striking beauty as attested to by the portraits displayed throughout the show in the Levis Gallery.

Andy Warhol declared her “the first girl artist with glamour.” This was meant as a compliment. He features her in several of his films, and she returned the favor with a sculptural portrait of him.

She often served as her own model. Her physical presence threads through much of the show. Four members of the quintet in “Jazz Wall” have faces modeled on hers. Tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims rounds out the band. Her wooden block sculptures “Big Boy” and “Big Girl” each holds a doll with the artist’s face. In “Diptych,” she creates a grotesque nude image by rubbing her oiled body on lithographic stones. And each of the 15 faces in her signature work “The Party” is hers. She said she used herself as a model because she worked in solitude, without an assistant. But there is also a sense that she was trying to center herself in the fragmented context of her biography and her times.

“I looked at my faces, all different in wood, and asked, Who am I?” she wondered.

The Toledo Museum’s purchase of “The Party” at auction in 2005 for a then-record price for one of Marisol’s works was an important statement, said Adam Levine, director of the museum. Now this show puts “The Party” in the context of her body of art. “Through doing this we can’t help but enshrine Marisol’s place in the canon for our audience and expose our audience to the full breadth of her work.”

“Marisol: A Retrospective” ” is organized by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum and curated by Cathleen Chaffee, that museum’s senior curator. The show is on exhibit in Toledo through June 2. Admission is $10, and free to members.

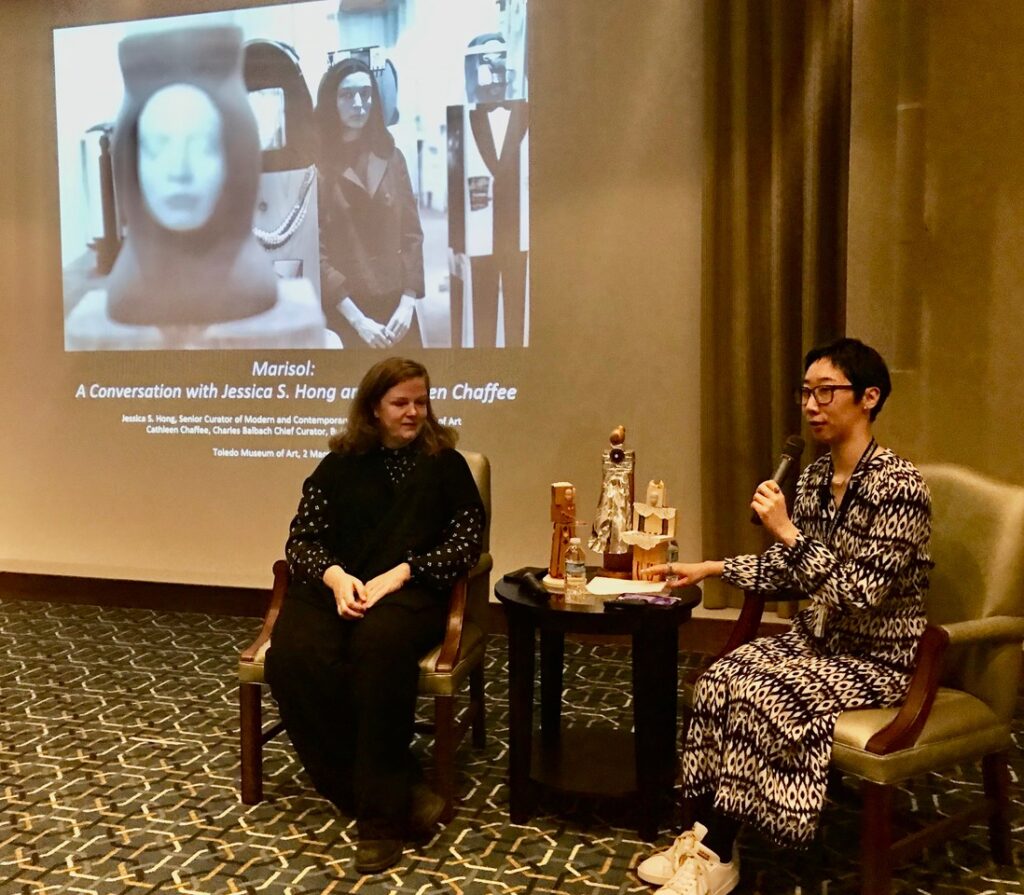

AKG bought Marisol’s first piece. Chaffee said other museums also purchased work from that first exhibit, but their check cleared first. Chaffee and Hong, who curated the installation in Toledo, had a conversation about Marisol and her work on Saturday.

Marisol remained grateful to the museum. Even though she didn’t have a particularly close relationship to the AKG, on her death in 2016 she bequeathed it her work and papers. Those form the backbone of the retrospective with the TMA’s “The Party” as the exhibit’s lodestar.

“The Party” it is in such demand that, for Hong who came to the museum in spring 2021, this is the first time she’s seen the work in Toledo. She had seen it in other shows. The installation also was restored recently.

It takes a place of pride with the show seeming to build to its appearance.

The show offers a preview exhibit in the gallery in front of the entrance to the Levis Gallery.

Panels and photographs detailing Marisol’s biography line the walls of the circular space. In the middle is “Mi Mama y Yo,” a striking image of her mother, who died by suicide when her daughter was 11. The mother beams, in her glory – there’s no doubt where the artist got her looks. But the artist depicts herself as child holding an umbrella over her mother, scowling. Sheltering her mother is a burden. She did not speak for a long time after her mother’s death, and had a reputation for being taciturn as an adult, Chaffee said.

That did not stop her from being the center of attention. She was covered, not just in art journals, but in fashion magazines.

As viewers enter the Levis Gallery they are greeted by a life-size portrait of the artist on a beach, after a scuba diving expedition. This is a foreshadowing of what’s the come, as are the earliest drawings done in color pencil crayon, ballpoint pen, ready-to-hand implements which give the drawings an immediacy.

Marisol briefly attended art school in Paris. The rigid studies that emphasized copying the classic works frustrated her. Not that she shied way from artistic rigor. From the start, her work displays a high level of mastery of her craft whether in wood carving or in draftsmanship or in the costumes and scenery she created for dancers.

While “The Party” may seem a frivolous society soiree none of the figures engages with any of the others. That sense of alienation reflects concerns of the time.

Her work has a subversive edge. One of the women in “Three Women with Umbrellas” is wearing a dress with an image of two Vietnamese women protecting their children from the violence of the war.

“Big Boy” dressed in red white and blue, holding a half-dressed doll, is Marisol’s sardonic portrait of the United States. Facing it is a celebration of an aspect of American culture. “Jazz Wall” is made of wood, with actual horns protruding from the surface.

Two display cases are filled items, magazine clippings, and photographs that inspired her work. It includes a photo of Sims, a noted jazz saxophonist of the time, as well as the studio portraits that inspired Big Boy and Big Girl. Marisol rescued them from a dumpster.

Magazines featured the early reaction, highlighting her physical appearance as much as her art. But Marisol wasn’t comfortable with the publicity, and left New York for periods of time.

During these travels she became a skilled scuba diver. This inspired an entire body of sea-based work. This is what elicited the “wow” from the toddler. There are elongated fish that share names with U.S. war ships. These pieces are beautiful warnings of how humans are destroying life in the sea.

The centerpiece is “The Fish Man,” an improbable mating of man and sea creature. The figure is crafted from wood with other materials as accents. Marisol uses the grain of the wood to dramatic effect.

Later in her career, she created public sculptures. These are the focus of the final gallery. Desmond Tutu, Father Damien, the builder of the Brooklyn Bridge loom large. Another, “The Funeral,” shows the iconic image of John Kennedy Jr. saluting his father’s funeral cortege.

One facing wall has drawings from late in the artist life when she was suffering from dementia. But even then, Chaffee said she retained her skill. These colorful drawings executed in crayon, ball point pen, and other ready-to-hand implements, echo those drawings.

These reflect images that stitch together the exhibit, projected in a variety of forms.

What finally emerges is a portrait of an artist who can wow viewers while making them reflect on their world.