By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Before Tuesday, this music was just a complicated series of marks on score paper, residing on computer hard drives and in the composers’ heads.

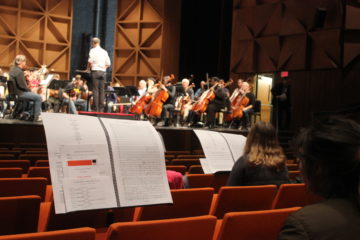

Then the Toledo Symphony Orchestra and conductor Michael Lewanski rolled into Kobacker Hall, and it all came to life in vivid orchestral colors. It filled the hall with brass chorales, tuba solos, swirling clarinets, flute melodies, the drone of double basses, harp glissandi, and swelling waves of strings. Sometimes the music was barely a whisper with the violins scraping their strings tonelessly and the brass players breathing through their horns.

The music of future had arrived.

Tuesday the sixth Toledo Symphony Student Composer Reading Session was held at Bowling Green State University. Each year five student composers, undergraduates and graduates, are selected to have their short orchestral pieces performed by the symphony.

The five composers this year were: Kory Reeder, Graeme Materne, Adam Kennaugh, Chuanhao Zhang, and Ashlin Hunter.

“For students to really hear these sounds played by high level professionals is quite exceptional. It’s really quite unusual,” said guest composer Andrew Norman, who would later meet with the composers to discuss their work.

The Los Angeles-based composer said when he was asked to come to BGSU, “I expected to hear fabulous new music.

“This university is known all over the country for being a center of really interesting progressive new music, and I wasn’t disappointed,” he said.

“There was so many different kinds of music being made, such a wide diversity of approaches to the orchestra, and each composer had such a different sonic identity.”

Merwin Siu, principal second violin and artistic administrator with the orchestra, echoed those sentiments. “You’re listening to people engaged in the process of finding their voice. They’re in various stages of that. When you hear somebody’s voice you think ‘wow, this person sounds like themselves, fully realized.’ That’s an exciting process.”

“The students make a huge leap in one day,” said Christopher Dietz, a member of the BGSU composition faculty who runs the event. “Sometimes education is incremental, and that’s good. Other times you need to have that road to Damascus experience.”

Each composition is played once through, then the student composer joins Lewanski at the podium and makes comments and takes questions from the conductor and members of orchestra. Then the orchestra plays the composition again.

Lewanski thanked the orchestra for its efforts. He said when they play it through the first time there are understandably problems. Then they address a few specific parts and play the piece again and “95 percent is fixed.”

The performance is recorded. That, said Hunter, is a very important element to add to her portfolio.

“You sit there and write dots on a page and you’re not sure what’s going to happen, and all of sudden you hear what it’s come to be,” said Materne. “It’s really fulfilling.”

“There were a lot of interesting things that I was excited to hear because I wasn’t sure it was going to work out,” said Kennaugh. “A lot of it was quieter than I thought it would be, but I thought it was also really effective.”

He explored instrumental textures in the piece that he’d not heard before and that he couldn’t replicate himself because he didn’t know how to play all the instruments.

“That’s the interest in research I have in the music I write,” Kennaugh said.

“It’s really different than hearing it on the computer” or in “your mind’s ear,” said Reeder. “To hear it physically manifested in the room, it’s odd but it’s cool, and it’s the best part about doing it.”

“It sounds different in this space with that many musicians,” Hunter said. “It sounds different than you think it’s going to.”

The young composers drew a number of lessons from the session.

Some were simple. “I forget how loud harps are. I thought it was going to be more buried in the texture, but she’s got some fingers,” Reeder said.

Others were more overarching. “Just get to work,” Reeder learned. Don’t spend a lot of time contemplating and planning. There’s so much logistically to do, and never enough time.

“So many things I need to learn – how to write a string part, and how to balance between string and woodwinds,” Zhang said.

Hunter said her issues had to do with the structure of her piece which involves “two musical narratives unfolding in space and through time.”

Hunter wrote in her program notes for “atrium”: “We use the same word for a windowed room and the chambers of our hearts. Light – like blood – must pass through the atrium to fill us with breath and life.”

Reeder’s “The Location of Lines.” was inspired by seeing the large-scale line drawings of Sol LeWitt at The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

Materne’s “Reverie,” sounded like full-throated film score for a daydream. Kennaugh’s “Impetus” evoked an image of a road trip interrupted by a hail storm.

Zhang’s “In the buried city, I heard the wind” was inspired by a narrative poem from northern China where he was born.

Using the colors of a western orchestra, he summons up a vision of mounted warriors coming upon a city devastated by war. Flute, clarinet and oboes play haunting melodies colored by Chinese tonalities.

The quality of the compositional work by BGSU students is what led Zak Vassar, the Toledo Symphony’s president and CEO, to initiate two new $5,000 scholarships for master’s students in composition at BGSU.

Vassar attended the readings session last November and was impressed by what he heard. “I felt we weren’t doing enough to nurture this talent.”

Starting next year, the university will give a scholarship to two students entering the master’s program with the understanding they will have a spot in the reading session in their second year.

Vassar said it’s even possible that if a piece produced by one of the scholarship winners is “really great” the orchestra may program it on one of its concerts.

While the TSO’s scholarship is a new financial boon for the event, an important early boost came from Karol Spencer, a supporter of the College of Musical Arts and former president of ProMusica.

“I love everything about this,” Spencer said as she hurried into Kobacker Hall a few minutes before the event was to begin.

She recalled six years ago encountering Dietz as he hustled frantically in the College of Musical Arts office.

She asked what was the matter.

He explained that he was organizing the reading sessions, but now as the deadline to finalize it was approaching at the end of the day, he was still short of money.

“How much?”

He needed $4,000.

Since she had a few minutes before her Pro Musica executive board meeting would start, she took out her checkbook and wrote him a check for that amount.

Spencer, a retired elementary teacher and the widow of long-time horn professor Herb Spencer, said she continues to give money to make sure the reading sessions continue.

She loves watching the students, and especially when their parents are able to join them.

“I just love seeing what happens to the students and watch them go on and do important things because of this rare opportunity.”