By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Since the green algae scare in 2014 that resulted in the Toledo area being warned to not drink the water, the Ohio EPA has insisted that Lake Erie would not benefit from being declared “impaired.”

But this afternoon, the EPA released a report stating the lake’s status should be changed to “impaired.”

The battle has been between the state – which didn’t want the region to suffer economically from being named “impaired” – and environmentalists, who said the lake would improve only if the source of the harmful algae is identified – and the farming community that didn’t want all the blame for the algae, and didn’t want more regulation of their practices.

In Thursday’s announcement, the EPA is proposing the open waters of Lake Erie’s Western Basin be designated as impaired for recreation and drinking water. This includes the area of the lake from the Michigan-Ohio state line to the lighthouse in Marblehead.

The shoreline areas of the western basin and drinking water intakes had already been designated as impaired.

This first assessment of Lake Erie included input from Bowling Green State University, Ohio State University Sea Grant College Program, University of Toledo, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. EPA. The report identifies a science-based process for assessing impairment from harmful algae of the western basin open waters.

“While designating the open waters of the Western Basin as impaired does not provide, as some suggest, a magic bullet to improve the lake, the state remains committed to our obligations under the Clean Water Act and to examine emerging science and practices that we can put in place to help improve it,” Ohio EPA Director Craig Butler stated in the report released today.

The news was welcomed by area environmentalists, who have insisted for years that Lake Erie would only get worse if the sources of the harmful algae aren’t identified and limited. The “impaired” status will require such studies.

While the farming community has made progress in self-monitoring and reducing phosphorus runoff that contributes to the algae, it hasn’t been enough, environmentalists said.

One of those applauding the designation is Mike Ferner, coordinator of the Advocates for a Clean Lake Erie.

“This decision that took massive public insistence and a federal court suit is way overdue, but let’s get down to work now. An impaired designation kicks off a process under the Clean Water Act that includes finding out exactly who the polluters are and the amounts from each,” Ferner stated in a press release. “It must be completely transparent, with public involvement every step of the way. ACLE will be vigilant to see that this declaration actually means something.”

Ferner has made repeated visits to the Wood County Commissioners, trying to convince them to sign onto a resolution designating Lake Erie as “impaired.”

“We think the voice of local government is important,” he told the Wood County Commissioners.

The “impaired” designation would trigger a full-scale investigation of all possible sources of pollution going into the lake, and then require action to reduce that contamination.

Ferner said similar action was taken in the Chesapeake Bay area, which allowed about $2 billion in federal funding to be used to solve the problems there. Prior to that, voluntary efforts were tried for nearly 20 years – but it was only when mandatory goals were set that the area recovered.

In the last couple years, the county commissioners also heard on the topic from Bob Midden, of the BGSU chemistry department.

Midden suggested that the commissioners look at strategies that have worked elsewhere. At stake are the economics of both the lake and agriculture.

“We don’t want to sacrifice one for the other,” he said.

Also at risk is the health of humans and animals. Midden said ingestion of the algal blooms can cause liver damage, gastrointestinal problems, and death to humans and animals. “It can kill people,” he said. And long-term exposure may cause cancer.

Midden warned that a lack of action will lead to disastrous results.

“We’ve got to get it under control,” he said. “You can consider Lake Erie to be a cesspool eventually if we don’t do anything.”

The commissioners have seen people point fingers at farmers for the problem, and farmers point fingers at overflowing sewer plants. Again, Midden suggested that the commissioners look at science for the answer.

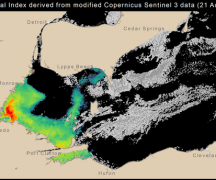

Midden showed satellite photos of Lake Erie, with consistent evidence that the algal blooms start at the mouth of the Maumee River and in the Sandusky Bay. The Maumee River algal bloom is always the larger one, he said.

Though some people have suspected that Detroit is adding to the problem, the photos showed very little evidence of that where the Detroit River enters the lake.

“You never see a bloom beginning there,” Midden said. “I think that visual is a good indication of what the source is.”

Midden gave credit to the farming community for working to reduce phosphorus and nitrogen running into waterways and eventually Lake Erie. Many farmers are using the “4R” approach of applying the right fertilizer, at the right time, in the right place, in the right amounts.

Not only does keeping the chemicals on farmland help the lake, but it also saves the farmers’ money. As far as manure placement on fields, Midden said if done properly, the recycling of nutrients is a form of sustainable agriculture. But if applied too heavily or before rains, it too ends up in the lake.

“As with anything else, it’s all about how it’s done.”

Some farmers take the steps of soil testing, drainage control and buffer strips – which all help. “I know there are farmers who are using the very best practices.”

But he also knows there are farmers who don’t follow those practices. And because of them, voluntary efforts to curb phosphorus and nitrogen in the lake may not be enough.

“If I was a farmer, I’d prefer voluntary measures,” Midden said. “But I think there are times when regulations make it fairer.”

He referred to the 1960s and 1970s when Lake Erie was in crisis. “The lake was nearly dead,” but requirements were adopted to clean up the water. “We can do that again. We need the will to do what’s needed” and the wisdom to know what that is, Midden said.