By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Professor Alberto Gonzalez has come a long way and not far at all. The first time Alberto Gonzalez set foot on the Bowling Green State University campus was when he and his twin brother, Gil, arrived to move into Kohl Hall.

Sons of a Mexican American worker from nearby Sandusky County, they hadn’t done college visits. For them even heading 30 miles west to Bowling Green was a major move.

In a way it was their generation’s migration. Their grandparents had been born in Mexico. Their parents were born in south Texas. They grew up in rural Riley Township near Fremont, and now they were attending college.

Alberto Gonzalez graduated from BGSU in 1977 before continuing his graduate work in communications at Ohio State where he earned a doctorate. He ended up returning home to teach, and at its February meeting the university’s board of trustees named him a distinguished university professor.

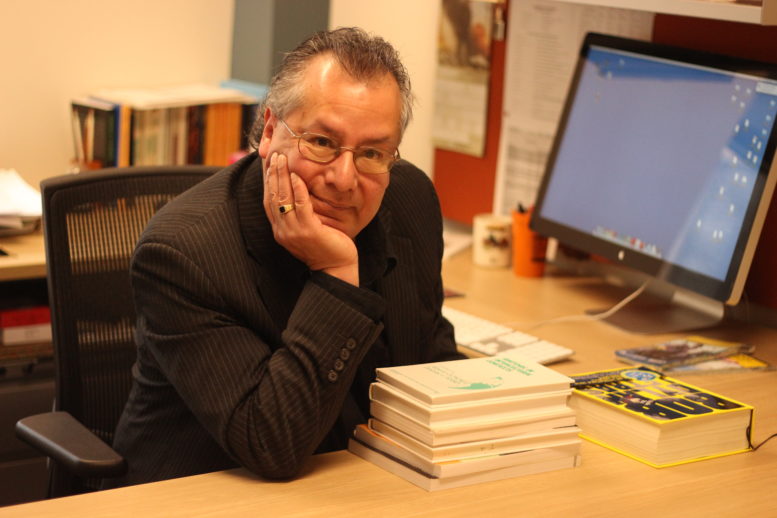

Alberto Gonzalez with one of his doctoral students Kisun Kim. He and his wife visited her parents when they were in South Korea last summer. (Photo provided)

Gonzalez, who has taught at the university since 1992, was pleased with the honor for more than what it said about him. “For me it brings attention to the School of Communications and speaks to the quality of work, the quality of research done in this school,” he said on a recent interview.

“You never do anything isolation. All the things I’ve been able to accomplish is because of having great colleagues around me and having great doctoral students. I learn from them and publish with them.”

In the resolution approved by trustees one of his former students, Eun Young Lee, was quoted as saying: “He provides me with a model for what it truly means to be an academic, which I am now trying to pass on to my students. … He has made me genuinely believe in and adopt the pedagogical value that each student in college deserves hearty and sincere guidance.”

Gonzalez said that the honor for him is also gives affirmation and encouragement to faculty of color and students of color.

Gonzalez has built his career on the scholarship in intercultural communication studies. He’s written books and articles and is the co-author of one of the most prominent texts “Our Voices: Culture, Ethnicity, and Communication,” now in its sixth edition with a seventh in the works.

Gonzalez learned early what it is to be ethnic. His mother died when he was 5, so he was raised by his father. His father, who worked for Whirlpool, had firm ideas about assimilation. Though Gonzalez said he only spoke Spanish until he was 4, his father insisted his sons speak English.

“He was afraid if we grew up speaking Spanish instead of English, if we were too ethnic, that we wouldn’t be successful in school, that we wouldn’t go to college,” Gonzalez said. “He tried to hook us up with majority culture and mainstream us as much as possible. Now he feels completely vindicated.”

Gonzalez is a Distinguished University professor, and his brother, Gil, is director of photographic services at the Hayes Center in Fremont, and also is an author.

His father encouraged them to read and allowed them to buy whatever books they wanted. He didn’t care what they were reading as long as they were reading. They developed their strong language skills.

Still “we felt in between. We didn’t feel completely included in the community. At the same time we knew we were different from the migrant workers who we’d see working in the fields or in the stores. We were also different than the locals. We were locals, but we never thought of ourselves as locals.”

This sense of being in between cultures pulled him toward studying intercultural communication.

In high school Gonzalez was active in speech and theater, so communication “seemed like a good fit” when it came time to choose a major at BGSU.

One day in University Hall, a theater student came and sat next to him because, Gonzalez said, “she thought I looked interesting.

They ended up marrying. He and his wife, JoBeth Gonzalez, have two daughters Monica and Veronica, both of whom have followed their parents to study at BGSU. JoBeth Gonzalez teaches drama at the high school. So to her students, her husband is “Mister Doctor G.”

He went on to graduate school at Ohio State, where he earned his doctorate.

Attending a Farm Labor Organizing Committee meeting where he heard Cesar Chavez also helped move him to studying intercultural communications. He noticed the different ways people communicated among themselves and with people outside their groups.

Different cultural groups use various strategies “to either intensify differences or create sense of similarity,” he said. “They can shift from one to the other, and what’s the implication of that on other cultural groups.”

His thesis was on Mexican political communications. More recently he’s written about how the Spanish-language newspaper La Prensa covered immigration reform during Obama administration and how that differed from coverage in the mainstream

His first publication, though, was on Bob Dylan. He was inspired to write about the future Nobel Prize winner after attending concert during Dylan’s born-again phase. He noticed how the songwriter used tropes from his earlier work to pull his older listeners in to what was seen as a change in direction.

“Rhetorical ascription and the gospel according to Dylan” appeared in the Quarterly Journal of Speech,” a top publication in the field. One of his OSU mentors quipped he had no place to go but down.

Where he and JoBeth did go was College Station, Texas, and then Minnesota. When their elder daughter was born they returned to Ohio to be close to family.

He’s remained here teaching, guiding doctoral students and being an administrator. He now chairs the Department of Communication Studies, his second time in that job. He’s also worked in the provost’s office.

Gonzalez has also been involved in the community. He was one of the founders of La Conexion de Wood County. He remembers the first gathering at the home of Beatriz Maya, who is now La Conexion director. “I thought I was going to a party,” he said. “It was a sales job.”

He knows first hand the need for support for those of Mexican heritage.

“The weirdness about it is I’m from Northwest Ohio and now a distinguished university professor. I’m about as much as an insider as anybody,” he said. “But I still feel vulnerable. Sometimes if I’m driving out in the county or even around town, I think all it takes is one overzealous police officer who’s into profiling and something bad is going to happen to me. If I’m feeling a little uneasiness and I’m one of the insiders, can you imagine how someone feels who may be undocumented? Who can’t pass in the community?”

In the sixth edition of “Our Voices,” a Taiwanese scholar wrote about how all the bureaucratic hoops needed to keep a current visa. People think being in the country legally is a simple issue, Gonzalez said, but it can change day to day.

“Our Voices” book, which celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2014, is ever evolving.

He always wants new cultural communities included. In the most recent edition, there was a piece on deaf culture. He’d love to have something on South Korean culture, especially K-pop music in the next edition.

Gonzalez still sees a lot of teaching and scholarship ahead of him. His academic connections present him with new opportunities. The past two summers he has spent teaching in Seoul, South Korea.

Next fall he’ll be on research leave. He’s looking at how the Mexican-U.S. borderlands are represented in film and wants to spend some time there to get context for the writing.

“I have no plans to slow down.”