By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The Syrian city of Palmyra was a crossroads in the ancient world’s global economy. In the second century A.D. the city called The Bride of the Desert sat astride the major trade route from Rome to the east. It was a place where cultures met.

Now Palmrya is in the crosshairs of global conflict that’s taken thousands of lives. Another casualty of the war in Syria and the emergence of ISIS is the ancient’s city’s cultural heritage.

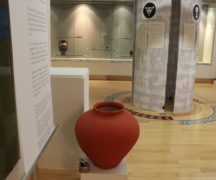

An exhibit in the School of Art, Palmyra: Exploring Dissemination, looks at the city though the lens of the ancients but also through that of the Europeans who visited its ruins in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The exhibit, in the lobby gallery of the Bryan Gallery in the School of Art, is the work of students in the graduate art history course, Iconoclasm: Ancient and Modern taught by Sean Leatherbury.

In its heyday the city showed the cultural influences of the Romans and the Persians. When Europeans started visiting the ruins again they were enthralled. The images shows panoramas of the ruins, some with stylishly dressed Europeans strolling about, and another with fancifully costumed inhabitants.

The cultural influences came together in the Temple of Bel, and that had an impact of European tourists.

“The Temple of Bel influenced architecture of that time,” Leatherbury said. “You go to a manor house in England and you can see ceilings influenced by the Roman Temple.”

But these ties to Western culture and to ancient pagan religion made them particular targets of ISIS.

ISI blew up the temple a few years ago. Another cultural victim was the great arch in the city. ISIS fighters wrapped it with explosives to take it down, Leatherbury said.

One of the students. Michael Kopp, created a short film that is projected as part of the exhibit, from footage of ISIS fighters destroying artifacts in the Mosul Museum in Iraq.

The class, Leatherbury said, explores the notion of iconoclasm through the ages.

It also touches on those who damage works in modern museums, as well as artists for whom destruction can be part of their work. Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei filmed himself dropping an ancient vase.

Each student selected an object and research it, then write explanatory paragraph for the exhibit guide. They include prints, drawings, and a stereoscopic image.

“The exhibit gives students a chance to approach the material they’re reading about in a hands-on way that gets them more excited about the context of the course,” Leatherbury said.

This is the second spring exhibit organized by a class taught by Leatherbury. Last year students organized an exhibit of seldom-displayed Greek antiquities from the collection of the Toledo Museum of Art.

Melanie Isenogle said she was surprised to learn after enrolling in the course that it involved curating an exhibit. She appreciates having the chance to learn about staging a show, and then having result on display in the School of Art.

Two of the objects on display are replicas made with a 3-D printer.

Mariah Morales had already studied the bust of Haliphat, which originally was in Palmyra, but now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Though that bust is safe, another 3D replica represents a statute of King Uthalm, which was one of the objects destroyed in Mosul.

Morales said that 3D printing gives viewers a greater sense of the cultural value of Palmyra and appreciation for the heritage that ISIS is destroying.

“This,” she said, “is everyone’s history.”

Also in the course are Justin Gerace, Dominique Pen, Jessica Allison, and Tami Landis.

The exhibit remains up through April 25.