By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Allie Terry-Fritsch wants her students to know what it’s like to do art history. In the course of their project Toledo Renaissance they touched on issues relevant to the present and future of the city.

Students in the seminar Critical Issues in Early Modern Art History presented a symposium at the end of the semester and staged an exhibit that’s still on view in the lobby of the Bryan Art Gallery in the School of Art.

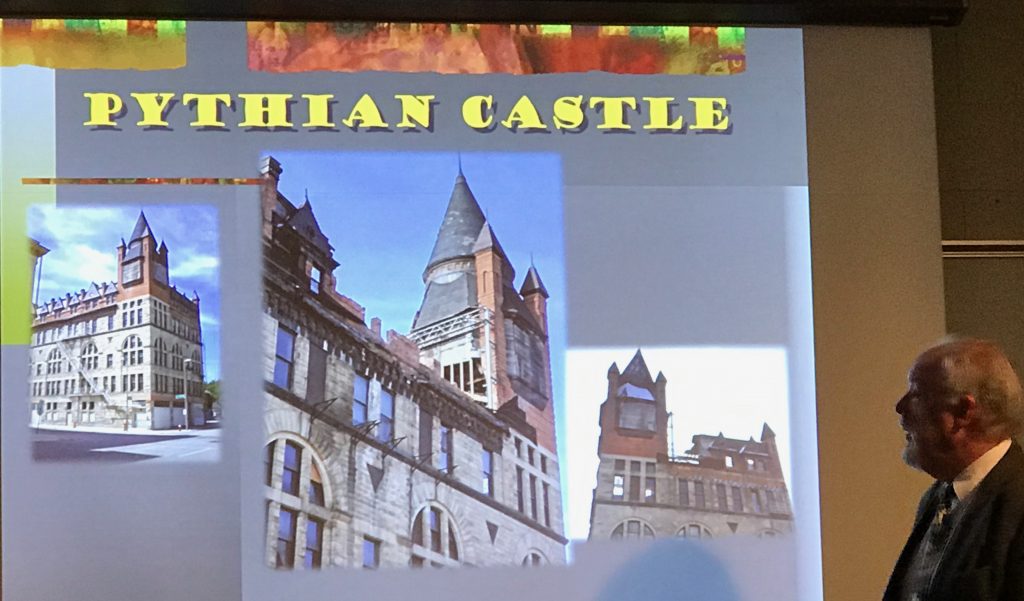

In the late 19th and early 20th century, America was coming into its own on the world stage, said Ted Ligibel, a noted historic preservationist who served as keynote speaker at the symposium. Americans wanted architecture as grand and beautiful as its new image.

Toledo was no different. For a model it turned to Europe, and the architecture of the Renaissance.

In his talk Ligibel noted the influence that pervaded the churches and public buildings of the city, some still in existence, many the victims of the wrecking ball.

Each student in the seminar researched one Toledo iconic structure.

The Nasby Building is a high rise built by famed architect Edward Fallis, who had his offices on the top floor well in the 1920s. Fallis, Ligibel said, was known for being extravagant, though that’s not evident in another of his designs, the Valentine Theater. Originally the Nasby Building was topped with an ornate tower. That’s now gone, as is the blue and white paneling that out-of-town investors has put up to cover the building’s exterior, loping off detail along the way. To their credit, Ligibel said, local architects objected.

It’s been on the “hit list” of previous mayors, Ligibel said, and is the focus of hope of being revived, and lifting the city with it.

Mitchell Taylor, a digital arts major with a focus on animation, studied the Secor Building, formerly known as the Secor Hotel. But when he searched online for the former name, all he got were listings for chain hotels, not the classic building he was seeking.

He sees it as an example of a renovated space now serving as breeding ground for new creativity. That’s happening in his hometown Cleveland, and he was heartened to see it here.

The seminar “opened up my eyes,” he said.

That was Terry-Fritsch’s intent. This was new territory even for the two students are from this area. Many of the students had never set foot in Toledo.

And this was the first time for most looking at primary sources — the documents from the time period itself that tell the story.

Terry-Fritsch studies the Renaissance Florence so she’s used to dealing with documents that are 600 to 700 years old and are housed in Europe.

Her students availed themselves of local archives at BGSU, University of Toledo, The Toledo Museum of Art and the public library as well as local history collections, such as the Toledo Police Museum.

They had to learn about research, then compile a catalog and present it, she said.

The cooperation of the local archivists was “a revelation” to the professor. “I want to continue working with this community.”

After his talk, Ligibel reflected on the issues of preservation. “I’m a firm believer that renovation happens when its time is ready. I’m always urging people not to tear something down right away because two, three, or four years from now someone is going to come along and say ‘I need a building like this.’”

He said: “The Notre Dame Mother House was tragic because easily could have been converted into other uses. Sometimes it’s done without forethought and seemingly driven by economics, but with older buildings you have to consider what they are and how well they’re built.”

Preservation makes environmental sense as well. He’s long been a proponent of the belief that: “The most sustainable structure is the one that’s already there. You can’t build your way into sustainability.”

Ligibel said it has been a struggle to get officials to realize the potential of these old buildings, given “how well they were built originally and all the embodied energy in them.”