By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

With a coat cloaking their heads, the citizens were blindly led into a room one by one. The coat was ripped off and before them was a man with a knife, or a gun, or a cell phone. Within seconds, the rookies had to decide whether to calm the man or shoot him. Whether to step back to de-escalate the situation or advance to diffuse a threat.

Some were left shaken by the experience – the responsibility of making snap decisions that could carry grave results for the victim, the suspect and the police officers themselves.

Sixteen citizens signed up recently to learn about policing in the Bowling Green community – with no idea what they would learn during their eight hours at the police station. They came from different backgrounds – university officials, city employees, Navy veteran, retail workers, recent college graduate, stay-at-home mom, and a reporter.

The purpose of the Citizens Outreach Program was to build a bridge between the Bowling Green Police Division and community members.

“This is a really, really important process you’re committing to,” Mayor Mike Aspacher told the participants on the first night.

The goal of the program was to find common interests, address tough questions, and ultimately build long-term relationships between the police division and citizens, Chief Tony Hetrick said.

“We wanted to hit the high points of policing,” Hetrick said. “We’re trying to demystify it, and promote understanding.”

The police chief has often stated that Bowling Green’s division doesn’t police the community, but rather polices for the community.

“We take very seriously our responsibility to provide for the health and safety of residents,” Hetrick said.

“We want to make sure everyone has a voice,” the chief said.

The COPS program was put together by Sgt. Ryan Tackett, who organized officers to present on their roles in the community, the weapons they are equipped with, and the situations they encounter.

The first four hours of class focused on patrol operations, crisis negotiations and special responses, the K-9 officer, and traffic stops.

On patrol

The police division gets calls about domestic violence, drunk drivers, thefts, power outages and couches left out in front yards.

Sgt. Jeff Lowery acquainted the class with the array of equipment carried by officers – everything from their 40-caliber service weapon, to tasers, and pepper spray (which is a “gift that keeps giving” for suspects and police officers). Officers also carry tourniquets, and are trained on how to apply them to accident or gunshot victims, Lowery said.

Each officer carries two sets of handcuffs, radios, a baton, and a body camera. The car dash cameras turn on automatically when the flashing lights are activated.

“They are very helpful in the prosecution of our cases,” Lowery said of the camera footage. “They give an accurate depiction of what occurs.”

Officers also carry two doses of Narcan to administer to people who have overdosed. This happens frequently, Lowery said, with three occurring in one day recently.

“Minutes can make a big difference,” he said.

Bowling Green’s police division has 41 sworn officers, 11 dispatchers, and one civil enforcement tech. Normally, there are four patrol cars and a supervisor on duty at any given time. The patrol numbers have been bumped up on the weekends in the downtown area given the number of fights and gunshots there in the past year.

“It’s a completely different town between the hours of 11 to 3,” Lowery said.

Lowery showed the class around the evidence room, which some noticed had a distinct smell of marijuana.

Officers are trained to recognize the signs of impairment from alcohol and drugs, and to conduct field sobriety tests.

“When you are looking at their eyes, they can’t hide it,” he said.

The police division has a couple portable breath machines, plus some officers have gone to advanced courses on recognizing drug impairment, Lowery said.

The police vehicles are all equipped with a laptop mounted on the dashboard. A concealed button must be pushed to access the rifles and shotguns. The backseats aren’t made for comfort, but rather for easy cleanup of vomit, blood and dirty dogs, Lowery said.

The police cars now have bars on the back windows. “We used to replace a lot of windows,” he said.

The COPS participants got an idea of the unknowns facing officers when they make traffic stops. In the dark, they walked up to a vehicle, to find a man lying in the back seat with a knife.

“It’s always an unknown what we’re walking up to,” Lowery said.

More mental health calls

More and more police calls involve people experiencing mental health crises.

One day during the week of the COPs class, police were called to a downtown coffee shop about a naked man who had walked down Main Street and into the shop.

“We have to make a quick decision” in such cases, explained Sgt. Scott Frank, who is the police division’s mental health liaison.

In this instance, the man told police he was not under the influence of drugs. He refused to put his clothes on, so police wrapped a blanket around him, escorted him out, and took him to the hospital for evaluation.

With many police calls involving someone with mental health problems, all the officers are trained in crisis intervention, Hetrick said.

“We made a commitment in 2003 to make sure all our officers were trained,” he said.

The police division is frequently criticized on social media by people who feel mental health issues should be handled differently. But the police say they are in an impossible position.

“Trust me, we have the same frustration,” Sgt. Gordon Finger said. “A lot of times it’s family members who call. We’re limited in what we can do if they don’t want services.”

The police division works with Unison, a mental health services provider, which has staff who will show up on the scenes.

A big part of police training focuses on de-escalation, which is especially important in instances of mental health crises, Frank said.

Crisis negotiation and special response teams

De-escalation and “active learning skills” are particularly important for the police division’s crisis negotiation team. Officers are trained how to best communicate with a suspect and negotiate a happy ending, if possible, Det. Matt Robinson said.

For cases where negotiation has failed or isn’t an option, some of Bowling Green’s officers are part of the Wood County Special Response Team – the sheriff’s local equivalent to a SWAT team. This group is trained to deal with barricaded people.

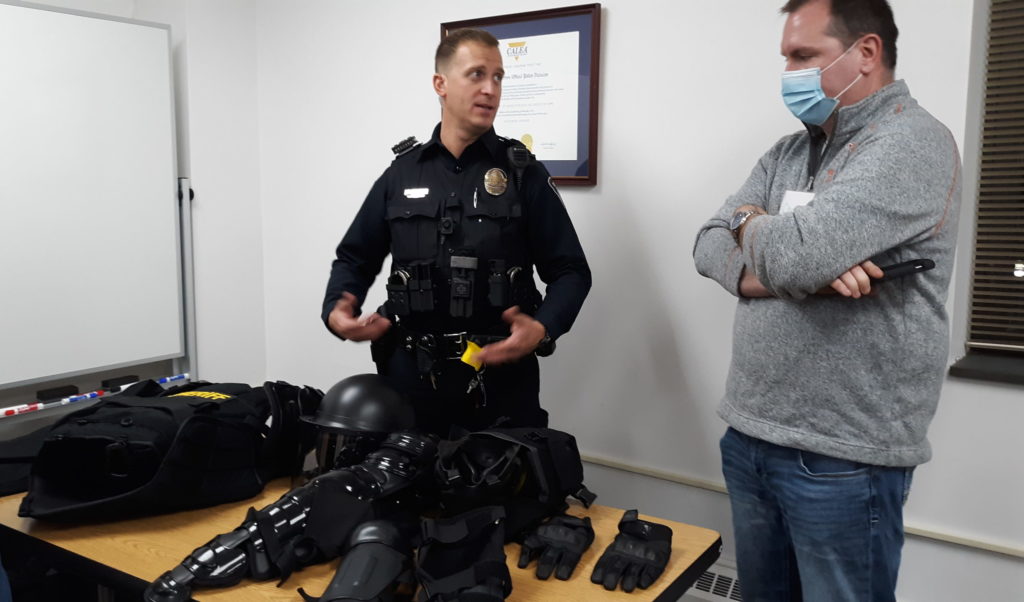

The equipment is specialized, including ballistic vests that can stop rifle rounds, ballistic shields and helmets, night vision goggles and battering rams to break down doors. The SRT members are armed with launchers that can propel non-lethal pepper spray in projectiles, and with rifles with red dot sight magnifiers.

Some officers are also part of a mobile field team with the Wood County Sheriff’s Office. The team could be called in for large acts of violence or riots.

Members wear protective gear that resembles baseball catcher’s equipment – except bullet proof – like Kevlar vests, elbow pads, shin guards, protective gloves, helmets and gas masks.

The goal of the team is to protect people and property.

“If people are peaceful, we don’t even need to get involved,” Officer Vincent Snyder explained.

K-9 Cop

Bowling Green Police Division also has one four-legged officer, Arci, who is trained to sniff out drugs and pursue people. With his human partner, Sgt. Gordon Finger, Arci exhibited his skills on Matt Bostdorff, in a padded practice equipment.

“My dog has never bit someone accidentally. My dog bites someone on purpose,” Finger said. “He is not a pet. He’s a working dog.”

Finger and Arci train weekly with 14 other K-9 officer teams from the region. The COPs program gave Arci the extra treat of being able to chew on Bostdorff in the decoy padding.

People trying to escape from the police are often more likely to stop in their tracks when they know a K-9 officer is in pursuit, Finger said.

“When I yell, ‘Police – you’re going to get bit.’ People stop,” he said.

Finger showed the class Arci’s motivation for doing his job – playing with his favorite toys.

“I am covered with slobber everyday,” he said.

Investigations

While some police calls are resolved in minutes, other crime investigations stretch on for months as pieces of the puzzle are put together.

Such are the cases often handled by Det. Sgt. Doug Hartman. The detective team investigates crimes like shootings, armed robberies, sexual assaults. Much of the job entails analyzing data and interviewing people. Trails are often left behind on cell phones and on social media – but that means sifting through a lot of worthless information in hopes of finding valuable clues.

The detectives work closely with the Bureau of Criminal Information and Identification, which has a regional office in Bowling Green.

Cases often hinge on DNA evidence.

“Fingerprints are kind of a thing of the past. Now it’s DNA,” Hartman said, explaining that criminals don’t even need to touch something to leave behind DNA.

Technology is on the police division’s side when tracking down suspects. A drone previously used for drug buys is now used by police to collect evidence. Old awkward Polaroid cameras have been replaced by digital cameras. Giant cassette recorders and wire recorders the size of garage door openers are now miniscule.

But technology isn’t always fast, with it taking several weeks to get some autopsy results, and up to six months to get some drug lab results.

Bowling Green’s lower crime rate doesn’t always rank it at the top of the “to do” pile. “They had 42 shootings last night,” Hartman said of Toledo’s demands on the labs.

Hartman shared the story of a Bowling Green man – who was a son, grandson, brother – and addict. “He would do whatever drug he could get his hands on,” Hartman said.

He showed photos from a happier time, when the young man was at a wedding. Then he showed a photo of the man dead from a heroin overdose in his Third Street apartment.

During the investigation, detectives read 1,000 pages of phone communications between a woman bringing drugs to him from Toledo. When the man texted he wanted “subs,” that meant suboxone. When the woman texted she was going to Toledo with her kids to pick up “Chinese,” that meant she was getting heroin. It was found that the woman also sold Adderall pills prescribed to her young daughter.

She was charged with involuntary manslaughter, for providing the drugs to the Bowling Green man. It was the first time such a charge was made in Northwest Ohio, Hartman said. She was sentenced to three years in prison – which she showed up to with pills stuffed in her bra, he said.

The class participants asked Hartman how he decompresses after working on such cases.

“I still don’t know,” he said “You can’t help but take it home.”

Use of force

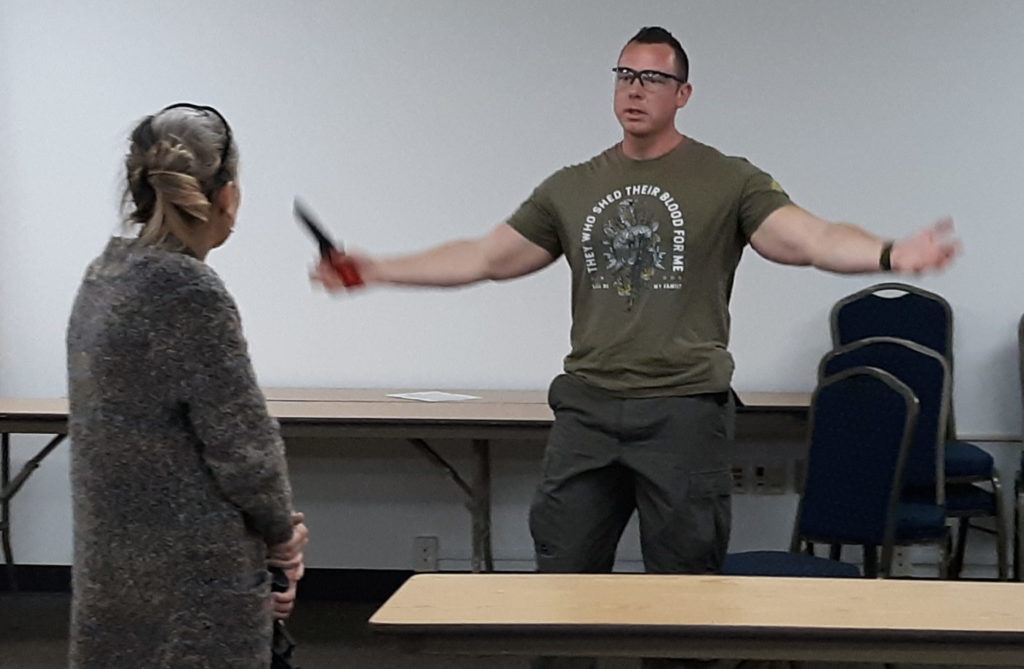

Deciding when force should be used, and how much is appropriate, is a skill that takes plenty of training, Frank told the class. There are reasons for using force – self defense, defense of others, defense of property, protection of evidence, protecting someone from themselves, and quelling civil unrest.

But the level used is important, he stressed.

“My presence itself is a level of force,” he told the class. An officer showing up on a scene may be enough to restore peace.

Officers have to make decisions based on what they know at that moment, paired with their years of training.

“We have to look at the totality of circumstances with the information known at the time,” without the benefit of hindsight, Frank said.

Bowling Green police train extensively on de-escalation. They are taught how to quickly create a rapport with an individual to influence his or her behavior, Frank said. Officers learn verbal and non-verbal ways to communicate and express empathy.

De-escalation leads to a “better outcome for everyone,” Frank said.

When force is used, officers must document it. And if one officer witnesses another using excessive force, he or she must intervene, he said.

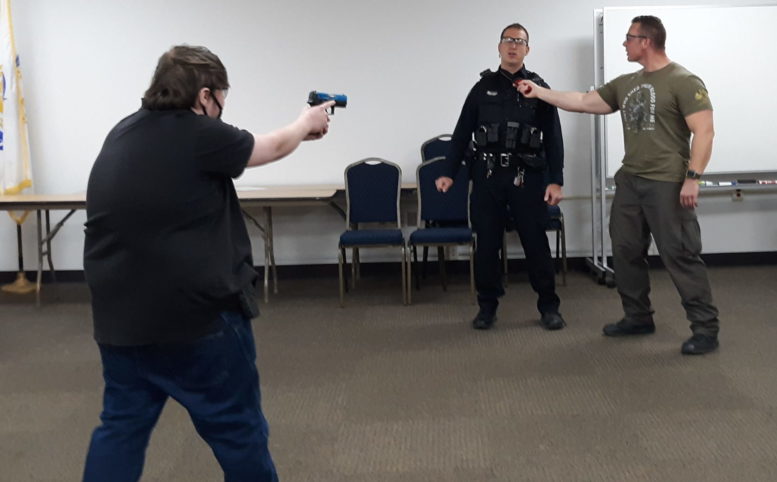

To show the difficulty of making swift decisions, the class was blindfolded and led one-by-one into a room – only knowing that they would be confronted and be required to act. The scenarios ranged from man with a knife feeling suicidal in City Park, a man stabbing someone downtown, a man threatening an officer with a knife after being confronted about shoplifting, and a man rushing at police with a cell phone asking how to get to Wood County Hospital.

The class participants were armed with fake guns that sounded like real guns, as they made snap decisions whether to de-escalate, shoot or offer directions. Several participants froze when confronted by a man shouting “I’m gonna f—– kill him,” and some shot the man running at them screaming excitedly about getting his wife to the hospital.

The class also had the chance to shoot real firearms in the target range at the police station. Some were experienced with firearms, and some had never fired a gun before.

“We treat every firearm like it’s loaded,” Officer Noah Crawford said as he prepared the class for shooting the Sig Sauer 40 caliber semi-automatic handguns.

What’s next?

The first COPs program got high ratings from the participants. Hetrick said he was pleased with the COPs class and the citizen participation, and hopes to offer the program again.