By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The Cost of Poverty Experience can be compared to the board game, Life.

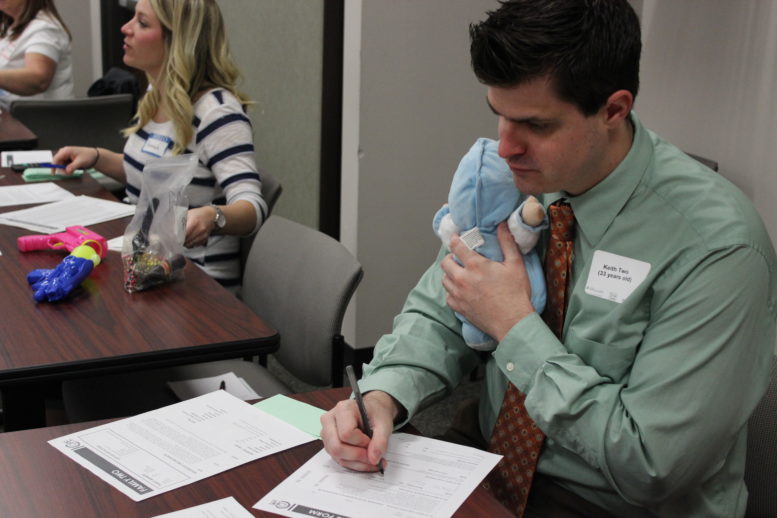

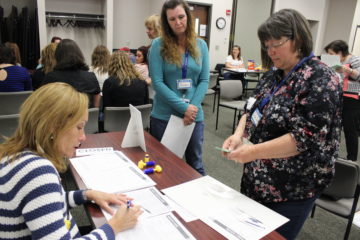

The players acquire tokens. Play money is exchanged as they move around the conference room at the Wood County Educational Service Center.

Except there are no winners, other than the owner the pawn shop or the drug dealer who preys upon the participants. And for these folks this may be like a game, but for the people they represent, the 26.5 percent of people in Wood County who live in poverty, it is not a game. It is life.

The simulation was presented by the United Way of Greater Toledo Friday morning for employees from a number of social service agencies, city government and one private company.

The simulation was presented by the United Way of Greater Toledo Friday morning for employees from a number of social service agencies, city government and one private company.

“I don’t have as many private companies as I’d like,” said Sue Clanton, of the United Way. Lubrizol did send a couple employees, she noted.

About 40 people clustered in the center of the room, formed into families of three or more, sometimes with three generations. They were given a scenario, and then had to figure out how to live through a week, a week that lasted for the purposes of the exercise for 15 minutes. In week that they had to find the money to buy groceries, gas, prescription drugs, get kids to school, work or try to find a job or apply for government assistance.

They faced long lines and sudden crises. They could be robbed, or caught up in a life of crime. The drug dealer offered cash, after all, to peddle drugs.

They went through four weeks. Once was a school vacation week. “You can’t bring your kids to work.” That money for some who watched after another family’s kids, and another expense for others. When someone showed up at the clinic to pick up a prescription, he was told he couldn’t because the family still owned the clinic money. Just as another woman got her application for assistance in, she was arrested on the suspicion of consorting with the drug dealer.

As serious as this was, there was laughter. Shocked laughter, or the laughter of recognition of being on the other side of these situations.

Madison Gornek, the AmeriCorps volunteer with United Way, who led the simulation, told those assembled that it was intended “to show you the true cost of poverty.”

After going through four simulated weeks, those assembled reflected on their experiences. And those in charge of the services, also made observations. Many families, for example, never showed up to buy food. And when asked if there was any family fun time, no one raised their hand. The rental agency ran out of eviction notices.

Several families ended up being evicted. The lucky ones had cars to live in.

For some it was chaos. They didn’t know where to go next for help.

“People in poverty don’t have time to plan,” Gornek said.

Sitting outside after the simulation, three employees of the Wood County Board of Developmental Disabilities, reflected on the experience.

Terrie Hunt said it shed light on the situation people living in poverty face. “You think you understand,” she said, but the COPE simulation put it in sharper perspective. In the exercise, Amy Carroll played someone with depression. Her character got her medication, but forgot to get a receipt. That simple mistake meant for one week, she had to “stay at home.”

That only made her psychological ailment worse, especially when paired with guilt.

Hunt, who played another member of the family, said it was tough ending the month with $5.

Carroll jumped in to say the family would have had $25 more if she’d remembered the receipt – the guilt from the exercise seeping into real life.

Melani Yarger played a teenager in another family. She was approached by the drug dealer who offered money her family needed to sell drugs. She didn’t accept and instead got an after school job. But concerns about that job became more important that what she was doing in school.

For her, it was valuable to be able “to just let yourself into that person’s experience and not judge.”

Hunt said she found herself getting excited when the family got a bit of extra cash and frustrated when things went badly. Also she got angry, Hunt admitted, when she went to seek help and the person was on the telephone. Why was that telephone call more important than assisting her?

Asking for help is difficult enough, Hunt said. “How we react can make all the difference.”