By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Jeff Fearnside finds it hard to pin down his muse.

Sometimes it expresses itself in poetry, sometimes in fiction.

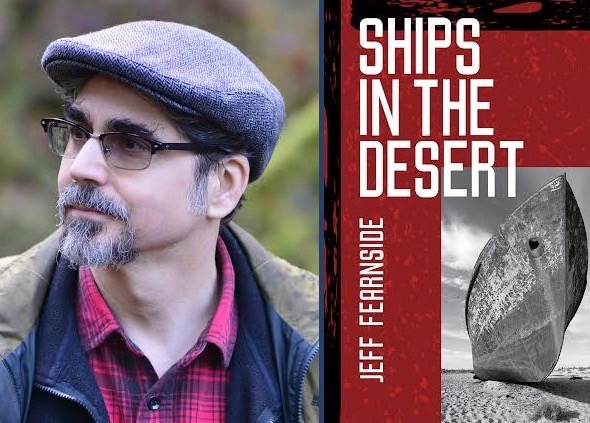

In his just published book, “Ships in the Desert” (SFWP) Fearnside explores non-fiction that combines personal experience with journalistic reporting and research.

The book brings him back to his experiences living and working in central Asia, primarily in Kazakhstan. He went first as a Peace Corps volunteer where he was a teacher, and then stayed to work as a manager for a non-profit.

“That was a life changing experience for me,” he said of his time in Central Asia. He has written about this period in his life before both in fiction and poetry.

[RELATED: Jeff Fearnside delivers short stories worth the wait]

“Ships in the Desert” is sculpted around two long essays — the title essay about the troubling and prophetic history of the Aral Sea, and “Missionary Position,” a rumination on proselytizing and propaganda.

Fearnside said he wanted to eschew the more typical literary journalism, which is character driven, more like a memoir.

“I knew I wanted to bring in what would be called literary journalism, reportage, because of the subject I was dealing with,” he said. “I just felt like it needed factual digging, so I kind of created this Frankenstein monster approach, partially reportage, journalistic, with memoir, and a type of travelogue. I didn’t have any particular model for this. I just instinctually felt I wanted to pull from all these disparate genres. It just seemed the right way to do this.”

The writer is no stranger to journalism. He started as editor of the Scarlet Parrot at Bowling Green High School, and later worked as a reporter for the Sentinel-Tribune and as an arts editor for the Boise Weekly.

The essay “Ships in the Desert” opens with two literary snapshots – one of the people who inhabit the area of the Aral Sea and another of the rusting Soviet-era fishing trawlers abandoned in the desert far removed from any water.

The reader rides with Fearnside on a dusty, bone-rattling drive to find what was left of the sea.

Fearnside juxtaposes the sad story of the decline of the sea — from the source of a verdant landscape that sustained residents to an arid, toxic wasteland because of overuse during the Soviet Era — with vivid descriptions of the arduous trip.

The essay was written not long after Fearnside’s time in Central Asia from 2002-2006.

While he drew on his own experience, “the story is much bigger than me and my time in Central Asia.” The story is much larger even than that of a dying sea in Central Asia. It is a global saga.

“Ships in the Desert” foreshadows the global water crisis that now touches close to Fearnside’s Oregon home. “It’s about a disaster that’s affecting all of us, everywhere.”

Lake Mead on the border of California and Nevada is at record lows.

The concerns he expressed in the essay “proved to be true,” he said.

The second central essay in the book, “Missionary Position,” was the first written. He began it while still teaching in Kazakhstan.

Fearnside was dismayed when his students asked: “Do Americans hate Muslims?”

“That bothered me,” he said. His impulse was to deny it.

“I wanted to say we have a lot more in common with you,” he said.

He also explores the rich cultural heritage of the region along the Silk Road. Not only were material riches traded along the Silk Road, but also spiritual ideas. It was a place where religious tolerance reigned.

Coming from his own religious background back in Northwest Ohio, he also understands the Christian tradition.

“We have our own heritage we want to bring to other people,” Fearnside said. “We should do so in a respectful manner.”

He paints finely nuanced sketches of the American missionaries he met. One told him he avoids the term “missionary” because of “the baggage” it carries. Still he admires much of what they do, but is critical of those “less than candid” about their intentions.

What began, he said, as “a plea for religious unity” turns into an examination of the varieties of propaganda. That includes religious propaganda as well as the virulent anti-religious propaganda of the Soviet era. And it includes those like himself, well-meaning Westerners who arrive with the best intentions to help. But aren’t they also peddling a certain world view?

No particular vision represents “the truth,” Fearnside writes.

In the end he concludes: “All we have is the religious heritage of the world and what we as individuals make of it. The path isn’t as important as the sincerity of the seeker.”

These expansive essays are flanked by more personal pieces about his students, and the persistence of his memories of Central Asia. The book begins with a portrait of his “host father,” a man just eight years older than Fearnside, who welcomed him into his family and culture.

Fearnside, who teaches writing at Oregon State University, continues to record his own search in books of many forms. He has three poetry collections making the rounds of publishers now.

His own path forward is uncertain. Right now he’s concentrating on promoting the book, and enjoying the ability to do live person-to-person readings again.

His writing is connected with promoting “Ships in the Desert.”

Starting a book project is daunting. He’s reluctant to dive in for fear it will “peter out on me.”

But he continues to write something pretty much every day.

As for the next big project, whether that fiction, poetry, essay or journalism, he’s taking his time. “I’m just waiting to see what speaks to me.”