By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

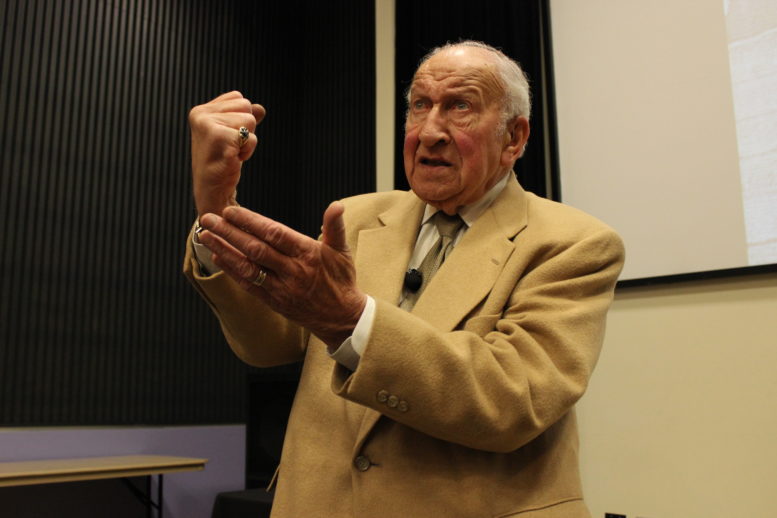

Martin Lowenberg grew to manhood despite the concerted efforts of the Nazis.

Lowenberg was 5 when Hitler came to power in 1933, and from then until he was finally liberated 12 years later, his life became increasingly hellish with death always at hand. “I faced the devil,” he said.

He lost his younger twin brothers and his parents to the Nazis. He lost his childhood. He did not lose his will to live.

He lost his younger twin brothers and his parents to the Nazis. He lost his childhood. He did not lose his will to live.

All this tragedy, he told, more than 225 in the student union theater at Bowling Green State University, was caused by hate. It is a word he wishes would be banished from the language. It is hatred of people of different beliefs that leads to so much evil. It leads to attacks like those at Columbine, Brussels, and San Bernadino. Hatred of people because of their religion makes no sense, he said. The event was sponsored by BGSU Hillel and the Office of Multicultural Affairs.

Showing a slide of his grandparents, he noted that they were buried in their village, but during the Holocaust their gravestones were toppled (and after the war erected again). His parents, he said, were not buried in the cemetery in the village they helped make prosperous. “Their ashes are scattered around Auschwitz,” Lowenberg told a rapt audience. “And every time I say that, it hurts.”

He doesn’t really know what happened to his younger twin brothers. He hopes they died with their parents in the gas chamber and were not subjected to the brutal experiments performed by Josef Mengele, who pulled twins for study from those flowing into the camps.

He doesn’t really know what happened to his younger twin brothers. He hopes they died with their parents in the gas chamber and were not subjected to the brutal experiments performed by Josef Mengele, who pulled twins for study from those flowing into the camps.

“I’ll never know,” Lowenberg said.

In her introduction Hindea Markowicz, of the Ruth Fajerman Markowicz Holocaust Center of Greater Toledo, said that the Holocaust was not carried out by the uneducated, but by the elite, doctors, like Mengele, engineers, lawyers, industrialists, psychologists and logistics experts.

All had a hand in the terror that befell the Lowenberg family and all the Jews of Europe. The Holocaust, she said, claimed the lives of a third of the world’s Jewish population, 6 million of the 11 million claimed by the terror.

Shortly after Hitler came to power, Lowenberg said, some drunken farmhands were urged on to burn down his family’s house because the Lowenbergs were “damned Jews.” The family was able to rebuild. His two older brothers were able to emigrate to Palestine.

Not everyone could afford to leave, Lowenberg said. They stayed as the Nazis closed in. When he was 8, at the urging of his teacher, Lowenberg was beaten up by schoolmates after the teacher falsely accused him of sticking his tongue out at the photo of Hitler in the room.

Not satisfied with the punishment meted out by his charges, the teacher made Lowenberg sit on a plank embedded with tacks and nails.

His family sent him to a Jewish school 150 miles away. He and the rest of the students could never go home, and they cried themselves to sleep. “We were so homesick.”

His family was eventually forced out of their new home. They had “to practically give it away” because they had to sell at such a low price and then were assessed “a Jew tax” on the proceeds of the sale.

They were forced to move to a larger city. Lowenberg was in class at the synagogue on the night of Nov. 9, 1938. He was seated in a classroom with other children when rocks were thrown through the windows seriously injuring some of his classmates. The children fled to their homes.

The synagogue, a grand edifice and the center of Jewish cultural and religious life, was burned to the ground. The windows of Jewish shops and homes were shattered. The night became known as Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass.

The next day a police officer and Nazi soldier came for his father. Though his father had served Germany as an officer in World War I, he was taken off to a concentration camp. This was a foreshadowing of what was to come. The camp system was being set up, Lowenberg said. The first to be interred were the mentally handicapped, homosexuals and those who had intermarried.

His father returned home, but had to do hard labor. The family had little food, except what friends brought to them in the dead of night. His older sister was working for a family and was able to emigrate with them. At 13 he was confirmed, but there was little on hand to have a celebration.

In 1941 they were made to wear yellow stars, identifying them as Jews. “Jude,” the stars said. Lowenberg said when he returned to Germany in recent years that’s how he was identified in headlines, “the Jew Lowenberg.” That attitude, he told journalists, is why there are no more Jews in Germany.

Already stripped of the German citizenship, all Jewish men were officially given the middle name Israel and all women the middle name Sarah.

“We couldn’t go out on the street,” he said. They were pelted with rotten tomatoes, stones, whatever was handy. Then on Dec. 8, 1941, “they told us we were going to be resettled.” They were told this was good. They could only carry a few days of clothes in a small suitcase. The rest of their belongings were to be packed away and their valuables taken for “safekeeping.” Then they were taken in cattle cars and box cars so crammed they had to stand during the long trip to Riga, Latvia. When they arrived they had to walk five miles in sub-zero weather to the ghetto which had already been emptied of Latvian Jews, whose belongings had been tossed into the frozen yards.

Lowenberg recalled they had no food. They could not pry the frozen loaves of bread left by the Latvians from the frozen ground. Yet they were forced to work. Still at night they returned home to their families. That didn’t last.

Soon all men between the ages of 15 and 60 were taken away. That’s when Lowenberg last saw his parents. The men were packed into barracks. They did slave labor. They subsisted on broth made from vegetable peelings and sometimes dandelions and grass. Then the Nazis took the elderly and children left in the Riga ghetto and sent them to the killing camps.

As the war ended, Lowenberg and others were marched away from the camps. The Nazis, he said, tried to burn down the barracks to hide the evidence of their atrocities.

Some of the internees were put in trucks with the exhaust pipes diverted inside to gas them. Lowenberg was not sent to one of those.

Asked if there was any individual who encouraged him to persist, he said, no. “Everyone had a load on their shoulders. We had to depend on our own selves.” As they endured “everybody had that hope to come out of this alive, to be a free person, to be liberated. Unfortunately for many of them, it never happened.”

His odyssey finally led to a rehabilitation camp in Sweden. He was 17 years old and weighed 76 pounds. At first he could stomach little more than a few spoons of milk or a poached egg. He found his sister Eva there, and their sister Margaret, who had fled Germany, located them and eventually brought them to New York.

At the end he encouraged the students to find who their true friends were. “Find the people you can trust,” he said. That was the key to getting on in life. “Life it is so important. We only have so many years to live.”