By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Traci Sorell has helped the Cherokee people in many ways.

Before she began writing for children, Traci’s work focused on helping Native Nations and their citizens. She wrote legal codes, testimony for Congressional hearings, federal budget requests, grants, and reports. Making sure elders could live out their lives in dignity.

Then her son was born. When she looked around, she found few books about indigenous people, and none about the Cherokee. And based on those few books, indigenous people disappeared after 1900.

The situation had changed little since she was young. She didn’t want him to read and “not see himself in the pages.”

So, she set about on a new mission, writing books about the Cherokee for her son and other young people. Now her son is 14, and his mother has published 11 books, enough to fill a shelf with two more on the way. Fittingly “We Are Still Here” is one of the titles.

Sorell visited Bowling Green this weekend through the auspices of BGSU’s In the Round series. The series brings in indigenous writers, artist, filmmakers, and others involved creative activity to speak about their work and their culture.

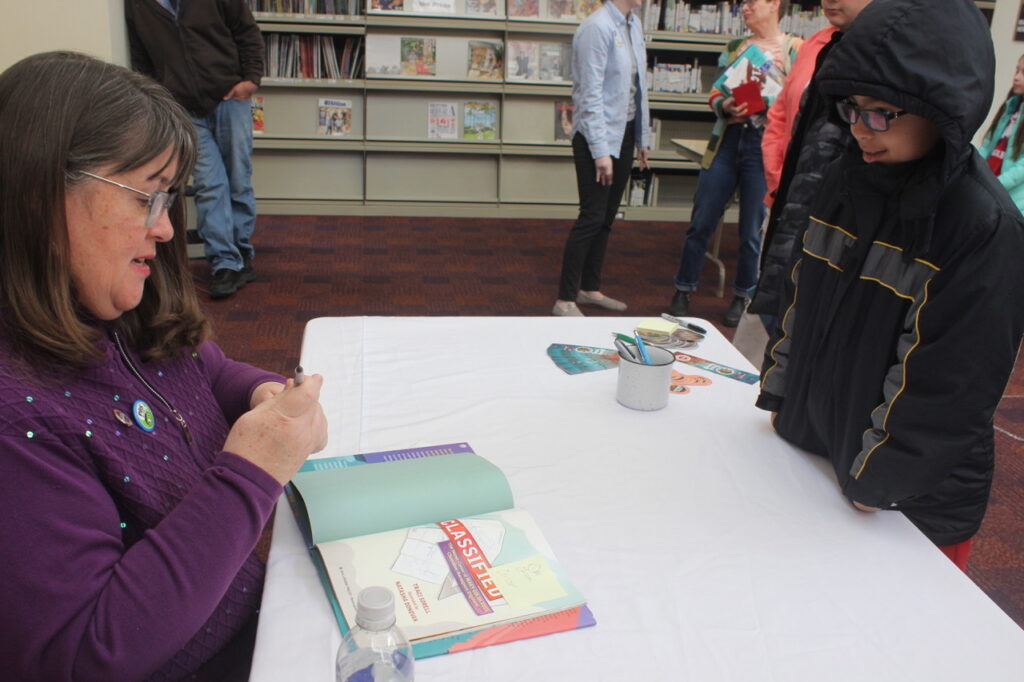

On Friday evening she spoke on the BGSU campus. On Saturday morning she visited the Wood County District Public Library.

“It’s amazing that in the last five years so many books by native authors and illustrators” have been published, she said. “What we see is not only accurate historical things, but native people in contemporary life.”

With more than 570 federally recognized native tribes in the contiguous 48 states and Alaska, there’s more books to be written to fully represent indigenous people.”

“Books are a wonderful way for kids are able to not just see themselves but see each other,” she said.

At Bowling Green, she read, with comments, two of her books, “Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer,” illustrated by Natasha Donovan, and “We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga,” illustrated by Frané Lessac.

Writing about an engineer was daunting, Sorell said. It was Ross herself who provided the focus. In 1999, shortly before her death at 99, she shared with a reporter her philosophy: “Do the best you can and search out available knowledge and build on it. I started with a firm foundation in mathematics and qualities that came down to me from my Indian heritage.”

Sorell shows how those qualities – humility, “working together in mind and heart,” and constantly seeking out knowledge, shaped Ross’ space age career: .

Sorell drew on the archive of Ross’ work, seeking the assistance from engineers to decipher the equations and drawings that are included in the text. Some of her work is still classified as top secret.

Ross was the great-great granddaughter of John Ross, the chief who helped to establish the Cherokee in what became the state of Oklahoma after their expulsion from the Southeast during The Trail of Tears. Sorell lives with her family on Cherokee land in Oklahoma.

Ross, who attended college at 16 and faced disdain from the boys in her math classes, started as a teacher, then joined Lockheed ‘s program to develop aircraft during World War II. Ross was accepted by her co-workers as a valuable member of the team. She became the first Indigenous woman to earn an engineering certificate. After the war, she was part of the top-secret team that worked on the nascent space program.

The second book Sorell shared was “We Are Grateful.” The book takes the reader through the year and shows how contemporary Cherokee mark the seasons, illustrating how the ancient ways still inform the life of the Cherokee.

The book includes Cherokee words, which Sorell had the audience pronounce together. She herself is still learning the language.”

The surge of book challenges and banning “truly disturbs me,” she said. “If kids can live it, kids can read about it. That’s what I loved about my local library – I could check out anything I wanted.”