By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Mary Beth Tinker was not a Communist at 13 years old. She was a Methodist.

Her father was a Methodist minister.

He and his wife raised their children, Tinker said, “to believe that understanding and good will and all those values that we learned were so important that we should put them into action on earth … right here, right now.”

For half a century Tinker has continued to do that as a nurse and an advocate for free speech, especially free speech for young people.

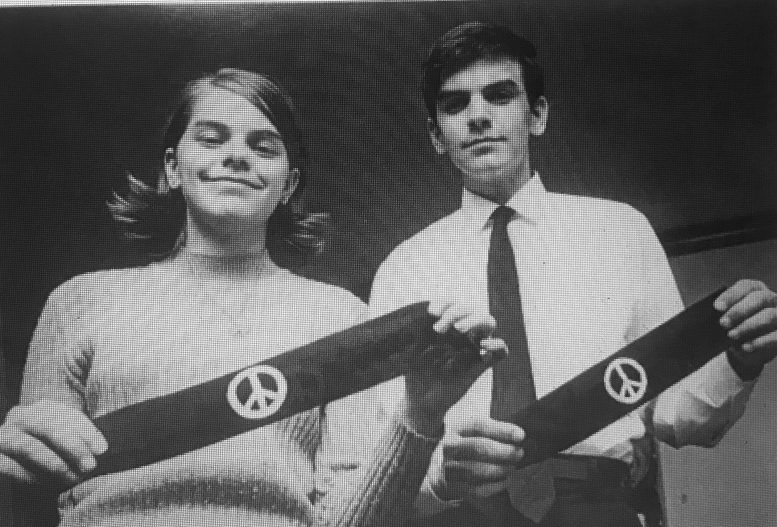

Action she took as a junior high student is what got her name in the law books. As a junior high student, she joined high school students, including her bother, in wearing black arm bands to mourn those dying in the Vietnam War. The students were suspended. The resulting lawsuit went all the way to the Supreme Court.

Tinker vs. Des Moines schools, along with Burnside vs. Bryars, a suit brought by Black students in Mississippi, set the precedent for protection of students’ free speech rights.

Pat Pauken, an BGSU faculty member and attorney specializing in education issues, said that he first encountered the Tinker case early in law school. Reading that case, he found “a love of free speech and the celebration of student and youth voices. … For 50 years Tinker has been gold standard for the recognition that children are people with heads and hearts and thoughts and feelings.”

It also serves as a reminder to teachers, he said, that they should give students opportunities to share those thoughts and feelings.

Tinker visited Bowling Green virtually Wednesday as part of Bowling Green State University’s Constitution Day celebrations. Constitution Day is today (Sept. 17) . In addition to Wednesday’s virtual community presentation, she visited with Bowling Green High social students, and two groups of BGSU education students.

While her action involved the Vietnam War, her activism was rooted in the civil rights movement.

She was inspired when at 10 she read about the Birmingham Children’s Crusade. Young people, just like her, marched when Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders were jailed in that Alabama city.

Police attacked them with fire hoses and dogs. On Sept. 15, 1963, Klansmen bombed a Baptist church killing four girls – Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Denise McNair, and Carole Robertson.

The next summer after three civil rights activists were killed in Mississippi by the KKK in collusion with the local sheriffs, Tinker’s parents traveled to Mississippi to help register Black voters.

They stayed with an elderly Black woman. Their hostess had them sleep in the back of the house so they would be safe when the shooting started. She stayed in front. She was used to it. In the middle of the night a pickup truck pulled up to the house and men inside started shooting at the house. Tinker’s parents came out and told the woman, who was huddled in the front, that they needed to call the sheriff. “Honey, that is the sheriff,” she told the couple. Her offense was trying to register to vote and housing the northern activists.

They came back to Iowa with those stories and lessons. And yet when Tinker and her brother proposed wearing black arm bands to school to mourn the deaths in the Vietnam and call for a Christmas truce, their father objected. School officials had banned the arm bands after they got wind of the plan, even though earlier they had allowed wearing black arm bands to mourn the death of school spirit.

Tinker and her brother repeated their father’s lessons to him. He would bring them to cemeteries to visit the graves of his friends who had died in World War II.

“He taught us that you have to stand up for you conscience because if you don’t you’ll have the Nazis in charge.”

He relented. Their actions led to their being suspended from school.

Their actions angered people in the community. They called the Tinkers Communists. Someone threw red paint at their house. They received threats that their house would be bombed. And Mary Beth Tinker received a call from a woman who told the teenager: “I’m going to kill you.”

Tinker said she was shocked when the Supreme Court ruled in their favor in 1969.

The two key points in the decision were that the action had not significantly disrupted school activities and that children were persons with all those rights and responsibilities.

Tinker went on to become a pediatric nurse, and that led her to recommit to being an advocate for the free speech rights of students.

As a nurse in an emergency room, she was treating far too many young people with gunshot wounds.

“I got so tired of taking care of kids who were affected so much by the policies of lawmakers, but the youth themselves didn’t have a voice,” she said.

As she began her presentation she celebrated those young people who had taken up the banner – young people advocating for greater protection of the environment, for racial justice, and against gun violence as well as more localized concerns like fairer dress codes at schools.

Just like when she was a teenager, “these are mighty times.”

“We’re again enduring great conditions of difficulty, and many are living in poverty, and it’s gotten worse,” Tinker said. And this has caused stress among young people.

Students are interested in addressing these issues. They care about free speech, she said, “because they have a feeling about being a discriminated group, most kids.”

She tells students that the First Amendment is like a muscle, it must be used or it will be lost.

It need not be an issue of global import, rather it can be about the length of time students have to eat, she said.

While teachers were encouraged to promote free speech among young people, the reality is they have fewer free speech protections in school than students have, Tinker said.

Nancy Patterson, the education professor who hosted Tinker’s virtual visit, said her discussions with a legal official at the National Education Association supported that point: Teachers are not positioned well to win First Amendment cases.

Instead they need to work with administrators and school board to establish local policies that protect them, Pauken said.

Even in the case of what is defined as hate speech, Tinker said, she favors dialogue over censorship.

Still there are limits when that speech impinges on the rights and safety of others. A Virginia school approved the display of Confederate flags – which Tinker had earlier tied to the KKK and white supremacists who perpetrated violence against civil rights workers – saying that no one in the school had a problem with them. No one, that is, Tinker noted, except the four or five Black students in the school.

Pauken said as a lawyer he tries to keep issues out of court. While one may win a legal decision that comes at the expense of the social and moral dimensions of the problem.

He recalled speaking with a class of mostly African Americans in Cleveland. Their discussion focused around the protests and counter-protests in Charlottesville.

He asked the class what they would say to someone involved in organizing the white nationalist march.

One young woman gave him the answer of a lifetime, he said. She’d say to them: “Hi! How are you?”