By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The students in Matching Faces with Places are all in their first year at Bowling Green State University.

The teacher for the class wants them to start thinking now of their life after graduation, when she hopes their BGSU education will be serving them well.

At that point the professor, President Mary Ellen Mazey, hopes they will remember the university and give back.

In the class, co-taught with Lisa Mattiace, the president’s chief of staff, the students meet models for that kind philanthropy.

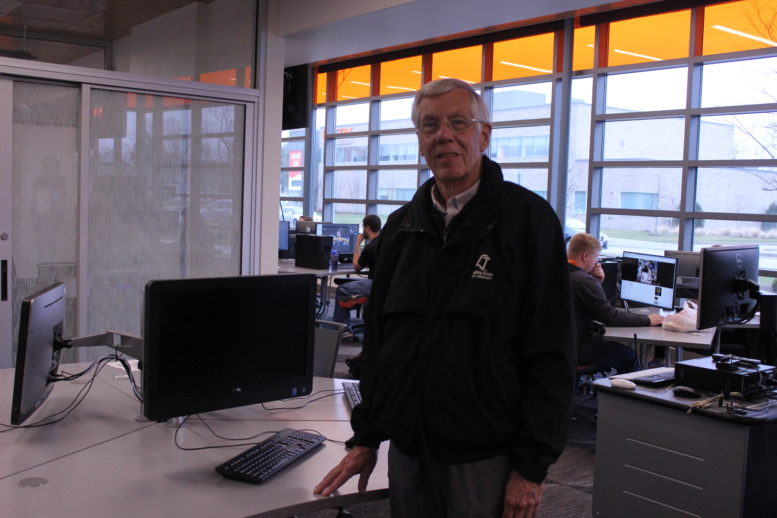

At a recent class they were seated in a second-floor classroom in the Michael and Sara Kuhlin Center, and their guest speaker was Mike Kuhlin, for whom the building was named. It was, he told the students, Mazey who insisted the building name use “Michael.”

And it was Mazey’s inspiration that led to the donation that put his and his late wife’s name on the state-of-the-art home of the School of Media and Communications in what had been South Hall, widely considered one of the dumpiest buildings on campus. That was before a $24 million makeover.

Kuhlin, a 1968 graduate in journalism, said for many years, he’d not had much contact with the university.

After working for a few years for the university in the placement office and doing graduate work in higher education administration, he went to work for Ohio Bell, and continued with the company through a series of mergers. He ended up retiring as Ameritech’s director of corporate communications.

Over many of those years, he told the students, he questioned the direction of his alma mater. As in business, Kuhlin said, “staying the same wasn’t good enough. That’s what this university did for a number of years.”

That changed when Mazey took over the reins six years ago. He saw progress on addressing infrastructure issues. The university also started reaching out to alumni it had lost touch with.

Kuhlin came back to the fold. “This happened because this place got better.”

Mazey said when they met two years ago, she was amazed at how much he knew about the university. His store of knowledge was “phenomenal.

“You want to know what you’re getting into,” he said.

“This university has gotten better since Mary Ellen has come. And the team that she’s put together is making this institution recognized in so many different ways that it never was before.

“We have to make sure that continues.”

He serves on the university’s foundation board.

Over the years the couple gave about $2 million to the university, including creating scholarships.

Kuhlin is pleased that the center that bears their name benefits students studying the same disciplines he did, and that it houses the BG News, now part of Falcon Media.

Mazey said that the Kuhlin donations were key in encouraging others to donate to the university’s capital campaign. That’s included recent donations of $12 million to turn Hanna Hall into the Robert W and Patricia A. Maurer Center, the new home for the College of Business Administration.

Mike Kuhlin credits his wife’s financial acumen with their having the wherewithal to be so generous. They had done well because of Kuhlin’s career with Ameritech, he said. But when he graduated from BGSU he was “the guy who had 50 cents in his checking account at the end of the month.”

He and Sara married in 1971 in Prout Chapel. At that point he decided that maybe getting a master’s in higher ed wasn’t the way to go, so he sought a private sector job. The job even paid more than he asked, $8,500 a year.

When the Kuhlins bought their first house, Sara said her salary would be dedicated to paying off their mortgage. When the mortgage was paid off, they started a savings program. That benefited not only them, but also those helped by the causes they donated to.

Their philanthropy was also shaped by Kuhlin’s experience in directing Ameritech’s giving program.

For many years, the program was run out of five regional business units, with the heads of each making the decisions, he said.

There were lots of $1,000 donations to people who knew executives. But Ameritech wanted more and turned to Kuhlin.

Now all the philanthropy flowed through him. “It didn’t go well that first year,” he said.

At the end of that year, the company had structured a program that set priorities about what non-profits it would help. “No more small contributions,” he said. “It had to be big enough to be meaningful.”

He’d run request through the various business units to see how it fit with their missions. “In the world of business you want to do good for both the non-profit and for the business.”

Kuhlin then could look at a donation, and say for that $10,000 gift the company would get $30,000 value back in promotion and exposure.

Over his tenure Ameritech’s giving grew from $17 million to $34 million.

Ameritech made sure its employees were there as Telephone Pioneers.

Kuhlin said that one of the principles that guided his and his wife’s giving was pairing money with time. The charities they favored were those where they had a personal connection, a dog rescue operation and Special Olympics. Kuhlin still uses the skills he first honed as a photographer for the BG News taking photos for the Special Olympics.

They also donated to two hospitals where Sara Kuhlin was treated for cancer before her death in 2013. Her cancer diagnosis is was got them thinking about making sure their philanthropy would continue after they were not around.

Kuhlin said as an individual donor it is important to target contributions. “You can go a lot of different ways and not be effective in any of them,” he said. ”As a donor it’s important to see how you’re benefiting and who you’re benefiting.”

So the Kuhlins set up scholarships to benefit those who show exceptional student leadership, which reflects his own experience when he was a student.

As students start life after graduation they have other priorities, but anyone who received financial aid should returning the favor to the extent they are able.

And, he said, don’t be concerned about giving large amounts. “If everybody gave $25 bucks we’d be so much better off at meeting the needs of the university and the students.”

Only 7 percent of alumni give to BGSU, Mazey said.

Kuhlin said that in a recent informational session with Cecilia Castellano, vice provost for strategic enrollment planning, he learned “that in a great percentage of cases a couple hundred dollars can make the difference between a student being able to stay at Bowling Green or not.”

If that student leaves, it also hurts the university because its state funding is tied to retention and graduation.

“If that happened for a couple hundred bucks, what a shame,” Kuhlin said. “I’m personally restructuring what I’m doing so some of that money goes into a retention fund for it’ll be there for a student who needs it.”

Kuhlin was asked how students could start giving back while still in school. Kuhlin said he’s impressed with the number of fundraising events held on campus. “Participation in those kind of activities is probably the best way to learn about the nonprofit side.”

The course is another way.

Alexis Kohl said she received an email, as did the other students, saying she’d been selected. “That makes you feel special.”

Wyatt Berezansky said expects he’ll donate to the university in the future, maybe $25 at first. “Hopefully more in the future.”

Eric Mintus has a clear idea whom he’d like to help — on campus, the Leadership Academy, which he’s involved with, and the College of Arts and Sciences. He also wants to help his church because that’s where he got his foundation.

The computer science major from Detroit said he’d also like to pass his knowledge onto younger people through mentoring.

Kohl said that the class has deepen her knowledge and connection to BGSU, and her sense of gratitude to those who make her studies possible. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for people giving back.”