By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Gov. Mike DeWine is enlisting farmers to help keep Lake Erie healthy.

“This is the crown jewel of the state of Ohio,” and some years that jewel is the color and consistency of pea soup. “We must get this right,” the governor said.

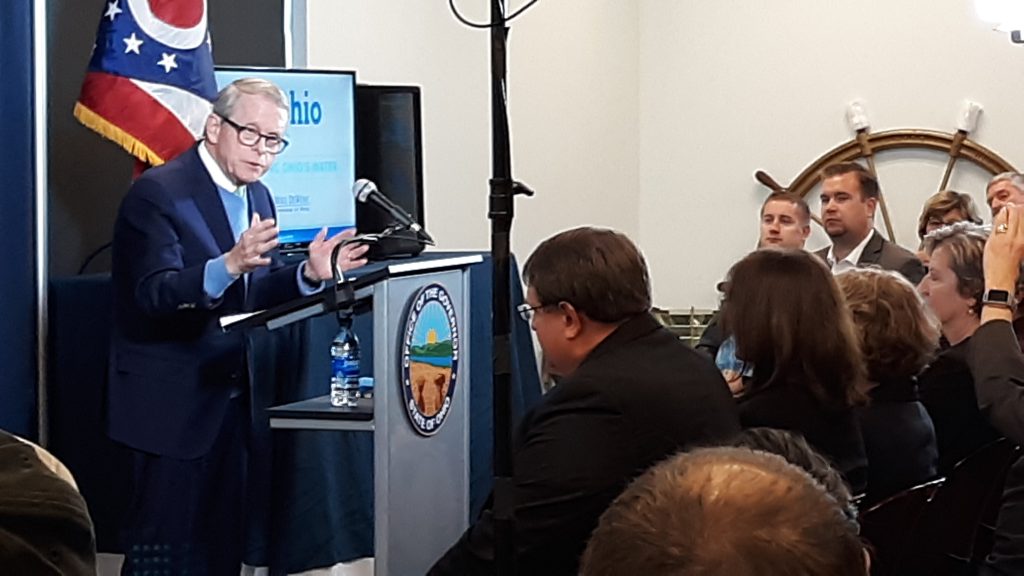

Earlier this year, the Ohio General Assembly set aside $172 million for the newly formed H2Ohio plan.

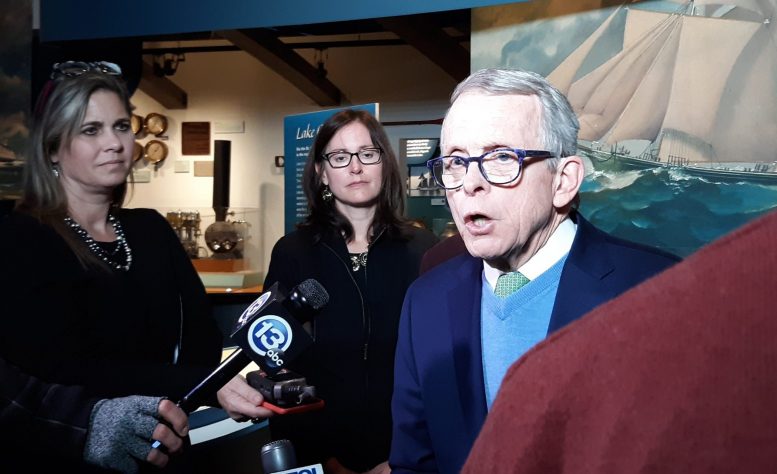

“Members of both parties have a passion to protect Lake Erie,” DeWine said Thursday to a room packed with politicians, plus people with ties to agriculture, the environment and economic development.

“We have a moral obligation to protect these great natural resources,” the governor said. And while farms aren’t solely responsible for the phosphorus causing algal blooms in the lake – they own the biggest share, DeWine said.

The H2Ohio plan is intended to be a comprehensive proposal – dealing with the hazardous algal blooms in the lake, but also with failing septic systems in rural areas, and with contaminated water caused by lead piping.

On Thursday, DeWine focused primarily on the problem of algal blooms in Lake Erie. The goal is to devise a long lasting answer to the green goopy water that can be harmful to humans, to tourism, and to economic development in the region.

“This addresses the causes of the problem – and not just the solution,” the governor said.

A team looked at 100 practices to reduce the amount of phosphorus draining off fields into ditches and streams – ultimately making it to Lake Erie. Those were narrowed down to the 10 most cost effective practices for farmers.

Those top 10 practices were unveiled Thursday by the governor.

DeWine acknowledged that past efforts to get the agricultural community to reduce runoff from phosphorus were less than successful. In fact, between 2014 and 2018, the amount of phosphorus making it to the lake went from 2.3 million pounds to 2.4 million pounds.

“Past efforts, although certainly well intended, did not work,” he said.

“We understand they must fertilize their crops,” the governor said.

But H2Ohio will help farmers fertilize in a way safer for the environment and more cost effective for them, DeWine said. The plan was devised by a team of people representing agriculture, conservation and the environment.

The key is putting the right fertilizer on at the right time, in the right place, at the right rate. Of course, if it were that easy, farmers would already be hitting all those goals.

So the H2Ohio plan offers help and incentives to farmers who follow the “best practices” set by the state.

“We are not expecting all of our farmers to use all of these practices,” DeWine said. “We do, though, need all farmers to participate at some level.”

The plan stops short of making the steps mandatory for farmers. The governor doesn’t believe that will be necessary, he said after his public announcement.

“I don’t think we’re going to have to cross that bridge,” he said.

Farmers will receive incentives for adopting the steps suggested by the state, and will save money by not flushing fertilizer into the lake, the governor stressed.

Following are the 10 best practices in H2Ohio to reduce phosphorus on fields from reaching Lake Erie:

- Soil testing: The results will give farmers information on how much and where to place fertilizer.

- Variable-rate fertilization: Applying specific fertilizer levels will be based on the need of each sub-acre to reduce fertilizer application without risk of losing yield.

- Subsurface nutrient application: Applying fertilizer below the surface to reduce nutrient loss.

- Manure incorporation: Mixing manure into the soil to keep it in place and minimize nutrient loss.

- Conservation crop rotation: Planting certain crops that reduce erosion and enrich the soil – consequently, reducing runoff and sediment delivery.

- Cover crops: When planted after the main harvest, cover crops reduce erosion, hold nutrients in the soil, and improve soil health.

- Drainage water management: Slowing down runoff will give phosphorus more time to settle back in the soil.

- Two-stage ditch construction: Creating modified drainage ditches will slow water flow and allow the phosphorus to settle.

- Edge-of-field buffers: When trees, shrubs or strips of grass are planted along farm fields in the right place, the plants hold on to phosphorus and prevent its release into the water.

- Wetlands: Wetland vegetation and soils absorb phosphorus, slow down the movement of water, offer a natural filtering process, and allow phosphorus to settle.

As part of the H2Ohio plan, counties in the Maumee River watershed will each have a localized phosphorus target to help ensure accountability. Individualized nutrient management plans will be developed for participating farms to identify which of the 10 best practices will reduce the most phosphorus runoff at each location.

“Each county and each farmer will have a stake in their success,” DeWine said. County soil and water conservation offices will be trained to help farmers enroll in the program.

The results of the farming practices will be public information, the governor said.

“We’ll be transparent with what we find,” he said.

DeWine cautioned that change might be slow.

“Ohio’s water problems took many years to develop,” he said. “Algae blooms will not immediately disappear.”

But the group called Advocates for a Clean Lake Erie has been questioning the effectiveness of the H2Ohio plan. The group has said that asking farmers to voluntarily decrease phosphorus runoff is not a strong enough step. The group noted that none of the H2Ohio funding is earmarked to identify individuals polluting Lake Erie or hold them accountable.

ACLE has stated that the “conservation measures” recommended by the state have been proven not to work.

In a press release, the ACLE referred to Ohio State University data showing that phosphorus levels in western Lake Erie began increasing in the mid 1990s when large “animal factories” started locating the watershed.

“Determining what’s needed is really not difficult,” the press release stated. “All you have to do is look at the source of the excess nutrients. The difficult part is standing up to the political forces that keep polluters insulated from accountability and keep Lake Erie toxic every summer.”