By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

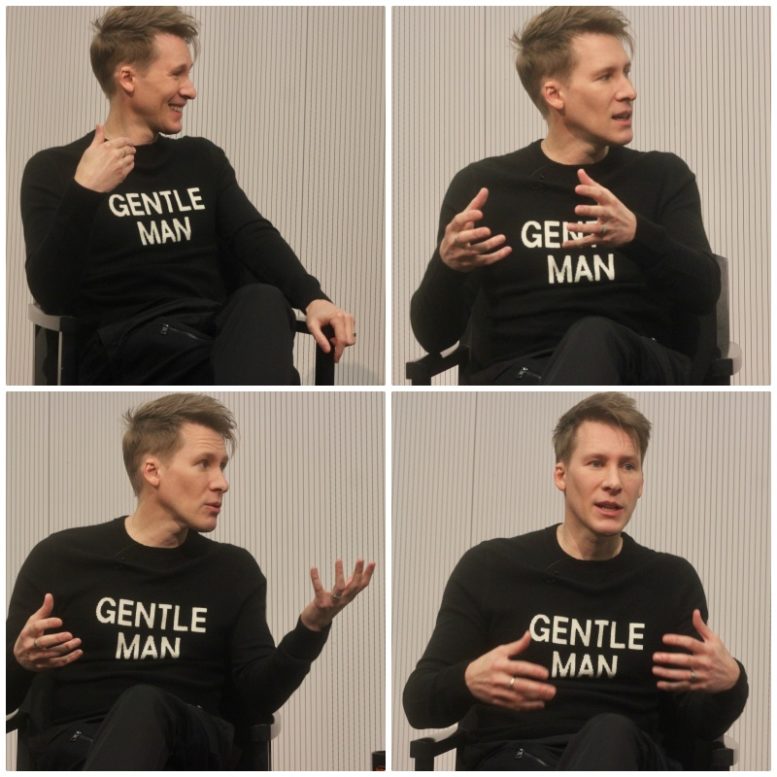

Dustin Lance Black believes in the power of stories.

Personal stories. Stories told while looking into another person’s eyes.

Stories full of granular, personal details.

Stories, Black told his audience Thursday night at BGSU’s Kobacker Hall, can be explosive.

“A powerful story,” he said, “is like a bomb. Lob it and create chaos.”

That’s what it will take to make “a better world for your children.”

So, he said in his introduction, “we can live in a peaceful country.”

To do that we must get beyond the notion that a person’s identity is defined by whether they put a D or an R on their voter registration card.

The Edwin H. Simmons Creative Minds Series speaker is an Academy Award winning scriptwriter for “Milk,” author of the memoir “Mama’s Boy: A Story from Our Americas,” and social activist. Of course, there’s a story behind all that.

Black started with his grandparents living in Louisiana. The area was poor and deeply racist. The Black residents, were the poorest of the poor, and lived on one side of the tracks. His grandparents, who were sharecroppers, were the only White folks who also lived there.

By the time Black’s mother had been born, his grandmother had a job and was able to lavish more attention on her seventh child, a daughter, Roseanna.

Then in 1949 when Roseanna, Black’s mother, was 2, she developed a strange sensation and then pain in her legs. It came on suddenly.

Her mother rushed her the hospital in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

When they got to the hospital their clothes were burned, Black said.

His mother was the first case in that area of a plague sweeping the country – polio.

His mother spent the next 14 years in the hospital. In an iron lung, having steel put in her spine, and other treatments that had little effect.

When she was released, a nurse handed her a list of all the things she’d never do – fall in love, go to university, have children.

Roseanna tore the list up and then spent her life crossing off each item on it.

When she married, it was to a guy seeking a deferment from the Vietnam War Era draft. They had three children, and he disappeared.

His mother found solace in converting to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In heaven, she was told, her body would be perfect.

She also joined the military.

At age six when Black learned in church that the worst sin after murder as homosexuality, he had already realized his attraction to boys.

Homosexuals would be “separated from their family for all eternity,” he was told. “I am that thing,” he thought, “and that doesn’t align with my mom, with the church, with the military.”

This was the 1980s, before AIDS, when gays were attacked, he said, by the left and the right.

“I knew I had a secret to keep,” he said, “and secrets breed shame.”

Even now gay kids are three to four times more likely to commit suicide than their straight brothers and sisters, he said.

Black contemplated suicide, but “I knew I didn’t want to hurt my mother.”

So he kept his secret. He brought it with him to UCLA where he studied film. He kept his secret from his mother until one Christmas, after avoiding any deep conversation with her, she drew it out of him. He betrayed his feelings with one single tear drop.

She asked her son why would you choose to be that?

He pointed to her braces and said why would you choose to be like that?

Heartbroken he returned to UCLA.

The night before graduation, he and his gay friends, had their own party. Most were alienated from their families. As the dinner was starting, he heard the distinctive click-clack of his mother in her leg braces making her way up the stairs.

Black evaded her all night. But she made herself at home, listening to the stories of his friends, who assumed she was the cool, accepting mother they all wished they had.

Finally at the end of the night, he and his mother sat down to talk.

She said she’d met the graduate student he was dating. “I met your friend … We had a long talk. I told him you need to take my son out on a proper date and because you’re older, you ought to pay.”

Black attributed this change to the stories his friends had told her.

She did not change her mind, but did make some space within herself to accept her son.

When Black received the Academy Award for the screenplay for “Milk,” a biopic about gay activist Harvey Milk, he spoke for the need to achieve gay marriage, and he promised to help make it happen.

His mother soon reminded him of that promise, and said he needed to keep it.

Black turned his energies to the fight for marriage equality.

The movement hired top attorneys , one liberal and one conservative. But they put the stories of those who suffered because they could not get married in the forefront as the case moved toward the Supreme Court.

“Being right is one of the most overrated things in humanity,” he said. “It’s better to tell the story. That reshapes the heart, that shows the humanity.”

When a lower court in California refused to allow video cameras in the court, Black turned the transcripts into a play that was shown on YouTube.

The movement won.

Black went back to Hollywood. His forthcoming work includes the television series “Under the Banner of Heaven,” which draws on his Mormon background, and a biopic “Rustin,” about Bayard Rustin, a civil rights activist and gay man.

While films, books, radio, and television are powerful media, the best place to ignite change “is the dining room table,” Black said.

He realized that he needed to go to Texas and visit his relatives, who were conservative and involved in an evangelical church that an uncle had founded, and tell his story and listen to theirs.

He talked to his cousins “eyeball-to-eyeball.” They shared stories about those they loved.

During the question and answer session at BGSU, Pella Felton said that for some transgender people like herself this kind of exchange can be dangerous. She spoke of a transgender woman, Ke’Yahonna Stone, who was fatally shot in Indianapolis on Dec. 26 while she was trying to break up a fight.

Black conceded that this was true, and that Twitter and other social media had a role in helping people share their stories.

From his own encounter with his family, Black realized their fear that a society in which resources were equally shared would mean there would be less for their children.

But such a society, Black believes, would mean more for everyone.

He is hopeful: “I do not believe we are at the pinnacle of human existence.”