By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The roots of the current immigration crisis run deep, and they extend to the seat of government in the United States.

The complexity of that web were traced during Pushed Out: Root Causes of Migration from Mexico and Central America Wednesday at a discussion hosted by La Conexion at the Wood County Library.

Valeria Grinberg Pla

Four speakers addressed the historical background of immigration from Mexico and Central America as well as current reality. They spoke both from scholarship and personal experience.

Valeria Grinberg Pla, a professor of Spanish American literature and culture, traced the violence that has sent so many Central Americans adrift. The U.S. had a pattern of interfering in the governments of Central American nations to promote the interest of American corporations, particularly those of the United Fruit Company. Any government that promoted land reform was likely to be overthrown. That happened in Guatemala in the 1950s, leading to 30 years of civil war, and in the 1970s in Nicaragua where the Reagan Administration backed a counter revolutionary force trying to overthrow the government, Pla said.

These countries as well as El Salvador all suffered from extended period of civil strife with Honduras suffering collateral damage from the neighboring conflicts.

And the aftermath of those wars has been devastating. Many refugees from the war ended up in the United States. The adults had to deal with dislocation and the trauma of war, Pla said.Their children faced cultural dislocation. Some joined gangs here in the United States as a way to cope. When they returned to their home countries, they brought gang culture with them.

Those gangs took root in the post-war landscape, Pla said. These Central American countries now suffer from the highest rates of non-military violence of any place in the world.

Those migrants, including those in the caravan on its way to the United are fleeing this violence, she said. “They are not economic migrants. They are not seeking a better life. For them, it’s a matter of life or death.”

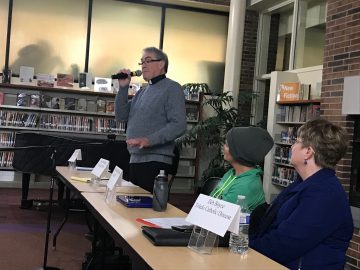

The Rev. Herb Weber speaks as fellow panelists Michaela Walsh and Deb Boyce listen.

The Rev. Herb Weber, of St. John XXIII Catholic Parish, first traveled to Central American about 30 years ago. He ventured to Guatemala when the civil war was still raging.

“After war, countries are not settled at all,” he said. Soldiers on both sides are no longer needed, and they still had their guns.

These were fertile grounds for criminal enterprises, he said. The gangs imported from the United States as refugees returned took root here. “The wars destroyed many lives.”

These threats sent families seeking safety abroad. For this they had to rely on unscrupulous coyotes, who extorted money and abused those who needed their help. Weber recalled one family that was brought to the Mexican border and then held in a tiny room for a month, until the coyote finally brought them to the desert to try to complete their passage to the United States.

Weber knows a Maryknoll priest who works with young men who want to leave the gang life.

They are marked for life with tattoos. The priest was able to get a donation of the equipment needed to complete the long process of removing the tattoos.

While the violence is a driving force for the refugees, at the bottom of it all is extreme poverty. “Why can’t they have a life where they can feed their kids?”

Michaela Walsh, who teaches Latino Studies at BGSU, said that the issues with immigration from Mexico date back to the end of the Mexican American War in 1848 when the United States annexed massive tracts of what is now the western United States including California and Texas from Mexico. This gave birth to the expression: “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.”

Walsh showed a photo of then First Lady Pat Nixon in 1971 helping to break ground for a friendship park near the border with Mexico. Nixon was offended because barbed wire was visible at the border. She had it taken down, Walsh said.

Since then more formidable barriers are in place, with calls for more.

The border is a desolate place here tractor-trailer trucks go to die, and where the United States is assembling prototypes of the wall President Trump wants to build.

But during World War II, when there were manpower shortages, millions of Mexicans were welcomed — after being showered with DDT — to come bring in the harvest, she said.

This established a pattern of transnational migration between the two countries with people moving back and forth across the border.

The signing of the North American Trade Agreements 1994 marked a major shift in relations, and migration patterns.

The agreement opened up the Mexican market to a flood of corn, beans, and rice produced by large-scale farms in the United States. Walsh said this displaced 2 million Mexican farmers, whose land was then taken over by multinational corporations.

In Mexico along the border, maquiladora plants sprang up to produce goods for the United States, taking advantage of lax environmental and labor regulations, and low wages.

Improvements in Mexico and a downturn in the economy here are serving to create a reverse migration. Some people return seeking better health care in Mexico.

Deb Boyce, of the Toledo Catholic Diocese, spoke of her 18 months of service starting in 2014 in Catholic Charities facilities that helped those seeking refugee status.

At first those fleeing in Central America were so desperate they sent their children alone with strangers hoping they would find new lives in the United States, she said. Then families came.

That’s when the U.S. government started separating children from families as a way of deterring the refugees.

People from 38 countries, from five continents passed through the Catholic Charities facility she worked at in McAllen, Texas.

They had been traveling for weeks, even months. One family from Eritrea took a year to reach the border. When they arrived at a port of entry, they would surrender. Then they would be separated and packed into facilities with little food and minimal sanitary accommodations in scorching hot temperatures. There they would wait as an understaffed government officials went through their case files to determine if they are eligible for asylum.

If their cases are found to be valid they are released with temporary protective status to those sponsoring them or with GPS tracking devices.

The Catholic Charities provided, Boyce said, “the first humanitarian” treatment they encounter in the United States.

They get food, a change of clothes, new shoes, and chance to bathe.

The Border Patrol is “not set up to take care of people in a humane way,” she said.

She asked those present to pray for the troops just sent to the border as well as the refugees heading there.