By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

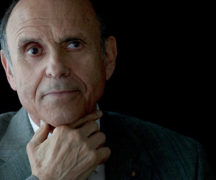

In selecting pieces for the three-disc set to mark his 90th birthday Samuel Adler and his wife, conductor Emily Freeman Brown, had plenty of music from which to choose.

After all, Adler has written more than 400 pieces dating back to 1953. They decided to focus on those that hadn’t been recorded. What resulted was an overview starting with his first symphony and including a piece from 2012.

During a recent interview in his Perrysburg home, Adler said of all the music he has composed it is his music for orchestra that he wishes received more performances.

Unless an orchestra commissions a work, the pieces tend not to get programmed. On Oct. 30, the Toledo Symphony will premier his tuba concerto.

So the birthday collection, “One Lives but Once” on Linn is heavy on orchestral pieces.

Freeman Brown, director of orchestral activities at Bowling Green State University, conducts the on the first two CDs. “Each has an early, middle, and late piece because they are very, very different,” she said. “The style changes and develops.”

The recording was “a very intense experience,” Freeman Brown said.

The project started with months of preparation. She had already conducted her husband’s first two symphonies. Still it was “a big, big process.”

“It was a great collaboration,” she said. “Sam was always here. We had lots of conversations months in advance. When we got there (Frankfurt, Germany) we had a really fruitful experience.”

The team included Linn recording engineer Philip Hobbs. “I felt the same way with the orchestra,” Freeman Brown said. “They worked incredibly hard and were extremely disciplined.”

That was necessary given the schedule they set for themselves to record one piece a day. “It was quite an experience, a communal effort,” Freeman Brown said.

Those are “typical American symphonies,” Adler said of the first and second symphonies.

The set opens aptly with Adler’s First Symphony which dates back to his tenure in Dallas.

He’d been hired in 1953 as music director of Temple Emanu-El after his stint in the Army, during which he founded and conducted the Seventh Army Orchestra (see related story).

A choral piece he wrote won a competition, and that led the Dallas Symphony to commission his first symphony. While in Dallas, he also began to teach at the University of North Texas, or North Texas State as it was known at the time. He helped found the composition department at the school most known for its pioneering jazz program.

Adler said Leon Breeden, who headed the jazz program, wanted jazz students should take classical composition. Adler even directed a group that improvised classical music. “We had a wonderful time,” Adler said.

His Symphony No. 2 is a tribute to his father, Hugo Chaim Adler, a cantor and composer of Jewish sacred music. Adler uses a theme from one of his father’s instrumental works.

Adler said like so many of his contemporaries he went through a phase where he devoted himself to serialism, a highly structured form of atonal composition. After a decade or so he decided “it didn’t suit me anymore. Now I write music the way I want to write music. I don’t care about styles. … I’m maximalist, not a minimalist, with lots of energy, I hope.”

That’s certainly true of his Concerto for woodwind quintet and orchestra, “Shir HaMa’a lot.” The title derives from the name of the ensemble, Ma’a lot Quintett, for whom it was composed. The quintet took its name, which means “ascent” from a sculpture by Israeli artist Dani Karavan. The quintet had won a competition sponsored by the Mannheim National Theatre Orchestra.

When Adler received the commission for the concerto, he inquired as to how he would be paid. Typically the composer would be paid by the German music licensing agency GEMA, but Adler wasn’t a member. He suggested that the orchestra reach out to a bank or other business, as is done in the United States. The first banker approached committed not just to paying for the concerto but also for a composer to write new piece for the orchestra for the next 20 years.

“Shir HaMa’a lot” is a traditional Jewish grace recited after meals. The piece captures the colors of contemporary music with lines that play with the tug of tonality, flowing full-bodied melodies, and rhythmic vitality.

Adler said that 13 years later, the bank president, who originally arranged for the commission, was retiring, and he wanted the orchestra to perform a dance suite.

These were not popular among orchestras now, but had been a mainstay of their repertoires in the 18th century. Adler obliged with “Man Lebt Nur Einmal (One Lives but Once),” which became the title of the celebratory release.

Adler’s mother, Selma, was fond of saying: “One lives but once, so one dances.”

The third CD was recorded at Eastman where Adler taught from 1973 to 1995, before finishing his teaching career at Juilliard, retiring in 2016. Adler met Freeman Brown, his second wife, at Juilliard where she earned her doctorate.

Adler sees his teaching and composition as related. “Students face the same problems you face,” he said. “It clarifies things in your mind. I’ve had the best students in the country, maybe the world.”

He’s also written key texts on orchestration and sight singing, and edited an anthology on choral conducting, which have been widely translated. Around the time of his birthday, he received a copy of his sight singing book from an Iranian musician, who had translated it into Farsi. Also, to mark his birthday Pendragon published his book “Building Bridges with Music: Stories from a Composer’s Life,” already in its second printing.

The Eastman recording sessions, included one orchestral piece, a concerto for guitar and orchestra, a piece for viola and guitar and a piece for violin and guitar

The session concludes with a choral piece, “Five Choral Scherzi” from 2008, appropriate given Adler’s prolific output for choirs.

There’s no stopping for Adler. Among his projects is an orchestration of a Ricercar from J.S. Bach’s “Musical Offering.”

“Every time I look at it, I think: ‘a human being can’t write something like this. It is so fantastic. It’s awesome in the right way.’”

Unlike many commentators, Adler is optimistic about the future of classical music.

“The whole thing of the death of classical music is idiocy,” he said. No, the music does not draw the throngs that Lady Gaga and other pop music acts do, but that was never the case, not in the days of Beethoven or ever. “It’s just the wrong psychology. It shouldn’t compete with popular music,” he said.

“It’s very much alive. People are writing as a much music if not more than in the classical period. We have fantastic orchestras all over the world. … Contemporary music groups are doing fantastic things.”

And as a conductor, author, teacher, and composer, Adler has contributed to that fertile musical environment.

“It’s been a wonderful life,” he said, “and a lucky life.”