By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When the humans in Sharona Muir’s new collection of short fiction confront their place in the universe, it is an exercise in humility. They are a small part in a vast, mysterious universe.

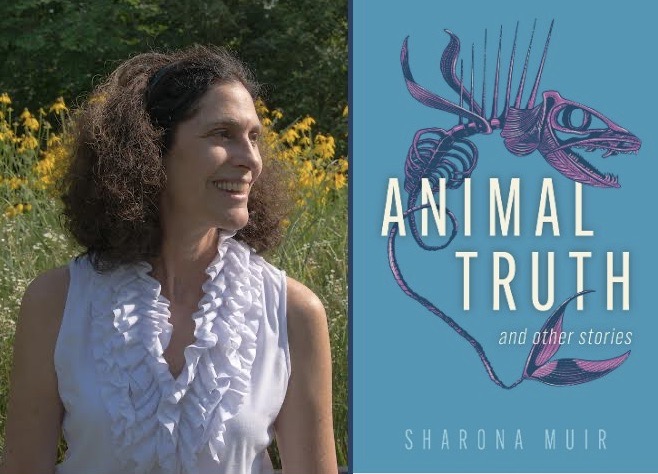

Muir’s “Animal Truth and Other Stories” comes out today (Nov. 22) on University of New Orleans Press.

“My writing for decades focused on the combination of science and imagination,” she said in an interview earlier this year. “Most recently I’ve been concerned with our ability to imagine ourselves as being animals within a natural order.”

Muir said that “scientists know these things intellectually.” That’s not enough for most people, though. “For people to really understand, to have a feeling of truth, we need story.”

Her mission, her passion, she said, is to write those stories. In her previous book, “Invisible Beats,” Muir created a menagerie of imaginary creatures. Even those were tethered to evolutionary possibilities.

“Animal Truth,” a collection of six tales, draws inspiration from the myths of the Greeks and the Romans.

“You have to have some humility,” she said. “There are animal truths about ourselves and we have to know them. Science helps us know them and we have to remake our old myths in order to understand ourselves in an era where it’s absolutely vital we understand our place in the natural order,” Muir said. “We can no longer pretend we are the lords of creation and that there’s a great difference between us and other species. … We have to understand ourselves from within the natural order.”

Those revelations can be shocking.

The title story, the centerpiece of the collection, draws its inspiration from the tale of Oedipus, the king who unknowingly kills his father and sleeps with his mother and is destroyed in the end.

In this instance, the characters are genetic researchers studying a rare fish that holds the key to curing a genetic disorder. Their work will make life better for some people.

But they must struggle with their own secrets, which emerge as the novella unfolds.

The message of the Greek play is “you can’t control your fate.” Sophocles wrote it, she said, as a warning against thinking critically and questioning the gods. The inference is no good can come from that.

But humans do question, and in “Animal Truth” that leads to troubling revelations that could threaten the vital research they are engaged in. “Incest is upsetting and disturbing,” Muir said. “It is a taboo in most of human civilizations. Something really fundamental to how we think about ourselves as human beings rests in that taboo.”

Though the story has one leg rooted in myth, the other is firmly rooted in the realities of science.

Muir consulted her geneticist friends about the science in the stories. She read scientific papers that “I only understood a 1/10th of.” All to make sure her science was plausible.

“Plausible in the sense that I’m using contemporary scientific ideas even if I’m using them in poetic ways,” she said. The fish at the center of “Animal Truth” is made up, but its evolutionary path was vetted by experts.

The story, “Animal Truth,” itself is an experiment: “What happens if you set this myth in a place devoted to controlling the very order of life, DNA?”

Yet the researchers cannot control the trajectories of their own lives, though they can decide how they come to terms with the truth.

That’s true as well for the artist in “Menu: Extinction.” He seeks to bring home the impact of extinction with a multimedia depiction of a feast where the last of their kind of mythical beasts are on the menu. He’s aiming to shock viewers by confronting them with the prospect of consuming the last Pegasus, the last mermaid, the last dragon, “the things that would instantly strike horror, “Muir said.

“Because the artist has had to go the source of human evil and callousness and greed, he basically summons the devil,” she said. “It is a story about the risks that the artist takes if you want to get to core of evil and express that in your work. He’s a little too cocky, and it brings the terror of extinction home.”

In other stories, the protagonists venture into the deep past, to the earliest days of the earth as we know it. One befriends a surreal ancient creature. Another, a weaver travels back to the beginnings of the universe, to find the design for a wall hanging.

Here the humans see how inconsequently they are in these environments that are a stew of life. Humans are less significant than the bacteria and viruses that have existed for eons, and created oxygen, and form DNA. “They are much older and much more powerful.”

Then there’s the meditation on “Bedcrumbs.” Muir writes: “Your sudden craving for a particular snack or drink after sex is the work of bedcrumbs.”

The book ends with “Weredogs.” A young woman, alone in her elderly aunt and uncle’s home during increasingly bad winter weather, confronts ghosts and her past, and in a flooded basement sees the face of God. Muir drew her inspiration for the face of God from Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, who has explored infinity in her work. She seeks peace in the world. “She thinks like God. She looks like God.”

[RELATED: Kusama’s ‘Fireflies on the Water’ submerges the viewer in a moment of infinity]

Muir said she feels bad for people who say that science takes away from the mystery of the universe. “Science is not capable of doing that,” she said. “It’s a source of joy endless mystery.”

In Judaism, her faith, “you cannot say what God is because there is no comparison. There’s nothing to compare the universe to.”

Science can discover new information about the universe. “With knowledge you gain humility and experience wonder,” Muir said. “Science cannot explain what the universe is because we exist within a mystery. … It’s a source of joy and endless mystery.”